AP Syllabus focus:

‘In BC-only topics, students interpret the arc length integral as distance traveled along a path in the plane, viewing length as another accumulation of change over an interval.’

Distance traveled along a planar curve extends the idea of accumulated change, using arc length to quantify motion along a path when direction varies continuously within the plane.

Distance Traveled Along a Planar Curve

This subsubtopic focuses on interpreting the arc length integral as a measurement of distance traveled, connecting geometric length to the accumulated effect of infinitesimal motion. In AP Calculus BC, this builds on the understanding that integration can measure not just vertical accumulation, but also the total length of a curve traced by a moving object in the plane.

When a particle moves along a smooth curve described by a differentiable function, the total distance it travels reflects the continuous change in its position. Because direction constantly varies, distance cannot be determined by horizontal or vertical displacement alone; instead, the path itself must be measured using an integral that accounts for the curve’s geometry.

Understanding Distance as Accumulated Change

The key idea in this topic is that distance along a curve results from adding up infinitely many tiny segments of motion. Each small segment approximates straight-line movement over a very short interval, and integrating these small contributions yields the total distance. This perspective emphasizes distance as an accumulation of arc-length elements, consistent with the broader theme of using integrals to measure cumulative quantities.

Arc Length as a Foundation

The concept of arc length underlies distance traveled along a planar curve. The arc length integral provides the mathematical framework for measuring curves that are not straight lines. It treats the path itself as the quantity being accumulated, rather than area or displacement.

When introducing arc length, we describe it as the total measure of a curve’s length obtained by integrating contributions from differential motion.

Arc Length: The accumulated length of a smooth curve over an interval, determined by summing infinitely many infinitesimal distance elements along the curve.

This definition helps establish why the arc length integral naturally represents distance traveled. A particle tracing the curve follows its full length, regardless of changes in orientation or reversal of direction within the plane.

Movement along a curve is fundamentally geometric, so the integral must capture both components of motion: horizontal and vertical. The rate of change in each direction combines to form the instantaneous speed of travel along the curve.

The Arc Length Integral for Distance Traveled

The arc length integral expresses distance traveled as an accumulation of small linear segments. For a smooth function on a closed interval, this integral uses information from the function’s slope to determine how “steep” the path is and how much distance is added at each step.

= Derivative of the function, giving slope and describing the curve’s steepness

= Interval endpoints, representing start and end of the motion

This equation shows that distance traveled accumulates contributions from both horizontal and vertical changes in position. The value under the square root reflects the relationship between slope and the length of the corresponding infinitesimal segment.

Thinking locally, each tiny step of motion can be viewed as a small arc length whose size is determined by how the curve moves horizontally and vertically.

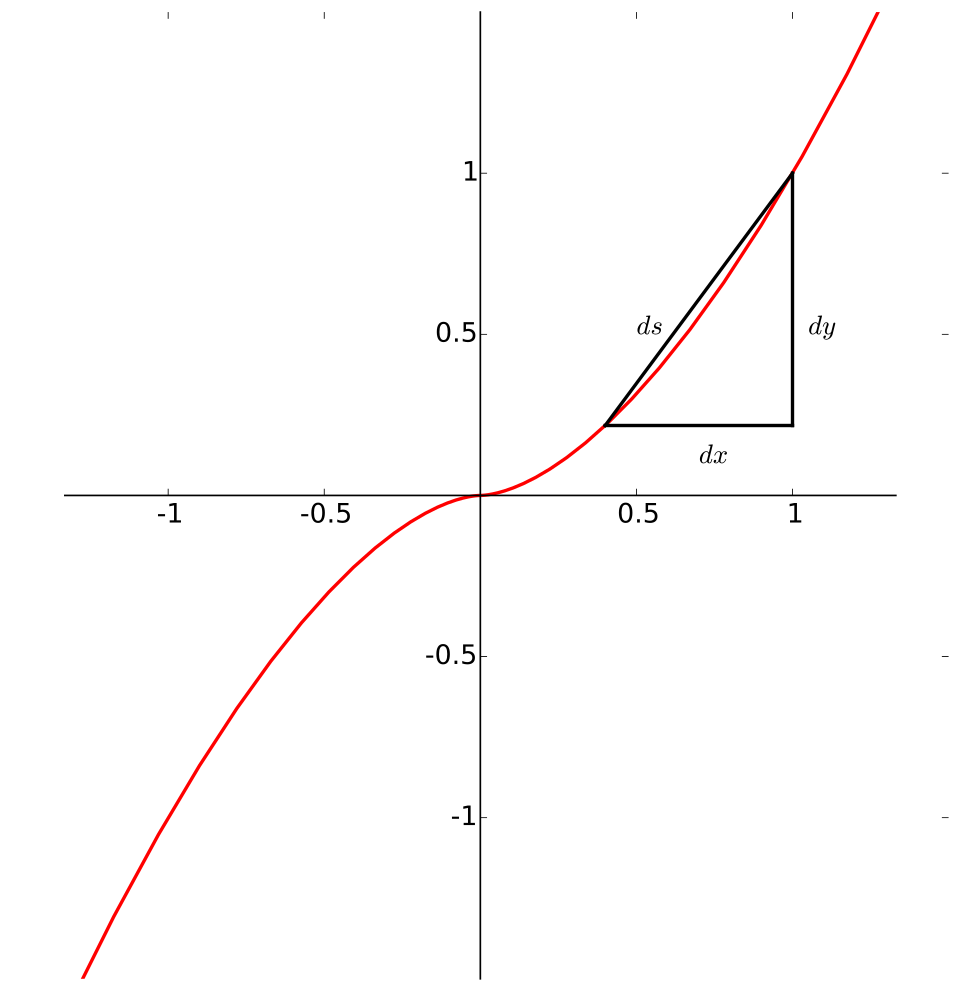

A smooth curve is shown with a small straight segment approximating the arc length , together with its horizontal and vertical components and . This illustrates how each infinitesimal change in position contributes to total distance traveled. The specific function used in the diagram is an extra detail and not essential for AP Calculus BC. Source.

When interpreting this formula in applied contexts, students understand the integral as a continuous sum of instant-by-instant magnitudes of motion. Even if the particle reverses direction or oscillates, the distance traveled always increases because length cannot be negative.

Conceptual Layers in Distance Interpretation

To properly analyze distance traveled along a planar curve, several connected ideas must be understood:

Distance vs. displacement

Displacement measures net change in position, while distance measures the total length of the path traveled. For curved paths, these values differ significantly.Motion through the plane

A particle tracing a curve may move horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, but the integral incorporates all such changes simultaneously.Slope as a contributor to distance

Steeper curves accumulate more distance even across the same horizontal interval, because greater vertical change increases the total length.Accumulation perspective

Distance is interpreted as the result of integrating a continuous rate of motion along a geometrically defined path.

Interpreting Distance in Terms of Motion

When viewed from a motion-based perspective, the arc length integral provides a measure of how far a particle has traveled in the plane, independent of its starting and ending positions. Students learn to think of the integral as capturing the total effect of tiny movements along the curve.

This interpretation reinforces the broader AP Calculus BC theme of using integrals to describe accumulation across various contexts. Whereas earlier topics focus on accumulated quantities like area, volume, and net change, this subsubtopic highlights accumulation of geometric length.

Using Graphs to Support Interpretation

Graphical representations often help students visualize the meaning of distance along a curve. A plotted path demonstrates how the steepness and curvature vary, clarifying why the integral accounts for changes in direction and slope. The curve’s overall shape indicates where the particle travels quickly through steep regions or more gradually through flatter segments, and the integral sums these contributions to give the total distance.

Conceptual Outcomes for Students

By mastering this topic, students learn to:

Recognize distance along a curve as the integral of arc length.

Understand that distance accumulates even when displacement remains small.

Interpret the integral expression as representing the geometric path of motion.

Connect rate-of-change ideas to geometric measurement in the plane.

View distance traveled as another example of integrals measuring accumulated change.

Thinking in terms of accumulation, the total distance traveled is the limit of a sum of tiny arc lengths and is expressed as an integral of the speed along the path.

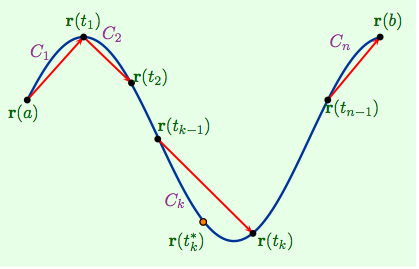

A blue curve is subdivided into short sub-arcs, each approximated by a straight red chord. This illustrates how summing these approximate lengths approaches the true distance traveled, represented by the arc-length integral . The specific notation in the figure is slightly more general than AP BC, but the geometric idea is identical. Source.

FAQ

When motion occurs in a straight line, integrating speed directly gives distance because the path does not bend. Along a curve, the direction changes continuously, so the speed reflects combined horizontal and vertical motion.

In curved motion, the distance integral effectively measures the length of the geometric path, not just how fast the particle moves in one direction.

A smooth curve ensures that the particle’s velocity changes continuously, avoiding corners or abrupt changes in direction that break the arc-length formula.

If the curve had sharp points, the distance would still be definable, but the standard integral formula might fail because the derivative is undefined or unbounded at those points.

Yes, but only in rare cases where the curve reduces to a straight segment.

If the path has any bending or turning, even slightly, distance increases while displacement only measures the straight-line separation between endpoints.

Parameterisation changes how the curve is traced in time but not the geometric shape of the curve itself.

Any valid parameterisation—faster, slower, or uneven—yields the same total distance because distance depends on the path, not the timing.

The expression for speed will differ, but the evaluated integral always returns the same physical length.

Distance travelled increases because it measures total path length, regardless of direction.

Retracing a section adds to the distance even though displacement may shrink or remain unchanged.

This distinction is critical: displacement accumulates net change, while distance accumulates all motion, including repeats.

Practice Questions

A particle moves along a planar curve given by y = f(x) on the interval 1 ≤ x ≤ 3. The derivative f'(x) is positive and continuous on this interval. Write an expression for the distance travelled by the particle along this curve between x = 1 and x = 3.

1 mark available

• 1 mark: Correct distance expression

Distance travelled = integral from 1 to 3 of the square root of 1 plus f'(x) squared, with respect to x.

A particle travels along a smooth curve in the plane with position defined parametrically by x(t) = t squared and y(t) = t cubed for 0 ≤ t ≤ 2.

(a) Write an expression for the speed of the particle at time t.

(b) Hence write a definite integral that represents the total distance travelled by the particle for 0 ≤ t ≤ 2.

(c) Without evaluating the integral, explain why the distance travelled is greater than the magnitude of the displacement vector from t = 0 to t = 2.

Question 2 total: 5 marks available

(a) 2 marks

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of x(t), which is dx/dt = 2t.

• 1 mark: Correct derivative of y(t), which is dy/dt = 3t squared, leading to speed = square root of (2t squared + (3t squared) squared).

(b) 2 marks

• 1 mark: Correct integrand: square root of (2t squared + (3t squared) squared).

• 1 mark: Correct limits of integration: from t = 0 to t = 2.

(c) 1 mark

• 1 mark: Explanation that distance is measured along the curved path, whereas displacement is measured in a straight line between the start and end points, so distance must be greater.