AP Syllabus focus:

‘Solids with semicircular cross sections use radius expressed from the base region; students apply the area formula for a semicircle and use a definite integral to find volume.’

Semicircular cross-section volume problems use integration to accumulate infinitely many thin slices, each shaped as a semicircle whose radius depends on the base’s geometry.

Understanding Solids with Semicircular Cross Sections

A solid with semicircular cross sections is generated when each slice perpendicular to a chosen axis forms a semicircle whose radius function depends on the base region in the plane. The key idea is that the base is already defined—typically by a curve, interval, or distance—and this base provides the diameter or radius needed to construct each semicircular slice. As the variable changes along the axis of integration, the radius changes as well, producing a three-dimensional solid whose volume is found by integrating cross-sectional area.

The Role of Accumulated Area

The semicircular cross sections are taken perpendicular to either the x-axis or the y-axis. At each value of the variable, a thin slice represents a semicircle whose area contributes to the cumulative volume. Because the definite integral represents accumulated area, it naturally adds all semicircular slices from the start to the end of the region.

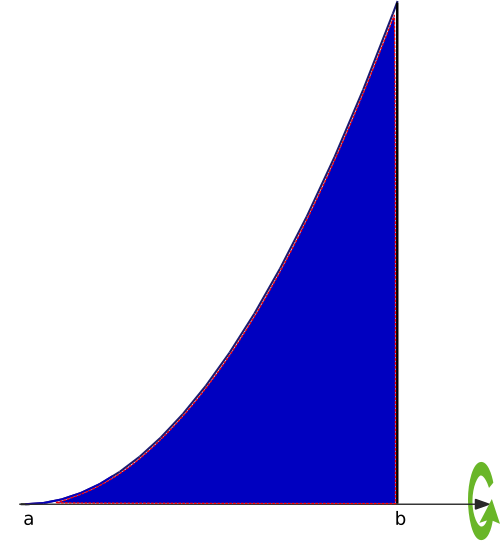

This diagram shows a general solid above the x-axis between x=ax=ax=a and x=bx=bx=b, with a thin vertical slice of thickness dxdxdx and cross-sectional area A(x)A(x)A(x). It illustrates the idea that volume is computed using the integral V=∫abA(x) dxV=\int_a^b A(x)\,dxV=∫abA(x)dx. Although the original example uses square cross sections, the same structure applies when A(x)A(x)A(x) represents the area of a semicircle. Source.

Identifying the Radius from the Base

The radius of each semicircle is determined by how the base of the solid is described. Students must interpret the problem’s setup to convert the geometry of the base into a radius function.

If the base is a segment of length or , that length usually represents the diameter, meaning the radius is half of it.

If the base is given by two functions, the radius may come from the vertical or horizontal distance between them.

If the base is a single curve above an axis, the radius may be the distance from the curve to the axis of reference.

This identification step is essential because the radius function determines the formula for the cross-sectional area.

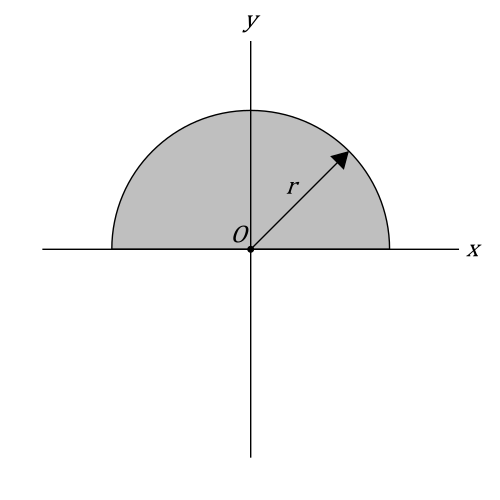

This diagram shows a semicircle of radius rrr centered at the origin, with the diameter on the horizontal axis. In semicircular cross-section solids, each slice takes this form but with rrr varying as a function of the integration variable. The figure also includes structural-engineering context not required here. Source.

Semicircle Area and Its Importance

The area of a semicircle depends on its radius, so knowing the radius function allows us to construct an expression for the area of each slice.

= Radius of the semicircular cross section

The semicircle's area formula provides the integrand for the volume integral, which is then accumulated across the interval that defines the base.

A correct radius function guarantees that each slice accurately reflects the shape of the solid. Misidentifying the radius—such as confusing diameter for radius—produces an incorrect integrand and volume.

Setting Up the Volume Integral

After identifying the radius at each point along the axis, the next step is writing the definite integral representing the entire solid. The integral accumulates the areas of all semicircular slices, treating each as an infinitesimally thin slab contributing a small amount of volume.

This image shows the region under y=x2y=x^2y=x2 on [0,1][0,1][0,1] and the 3D solid formed by revolving it about the x-axis, illustrating the stacking of thin slices to form a volume. Although this figure uses full circular discs, it highlights the same “slice and integrate” structure that applies when slices are semicircles. It visually connects a planar base, a known cross-sectional shape, and the integral that computes volume. Source.

= Volume of the solid

= Area formula for a semicircle

= Radius expressed as a function of

A similar structure is used if the slices are perpendicular to the y-axis, replacing with and integrating with respect to .

A well-organized setup ensures that the integral matches the geometry of the solid. The integrand must represent area, and the bounds of integration must match the domain over which the cross sections exist.

Determining the Orientation of the Cross Sections

Choosing whether to integrate with respect to or depends on how the base region is described. Correct orientation simplifies the radius function and typically avoids piecewise descriptions.

Guidelines for Choosing Orientation

Integrate with respect to when cross sections are perpendicular to the x-axis.

Integrate with respect to when cross sections are perpendicular to the y-axis.

Select the variable that keeps the radius expression simple and continuous over the interval.

Prefer the orientation that avoids multiple integrals unless the geometry requires a split.

This decision directly affects how students express the radius and how the bounds of integration are determined.

Visualizing the Geometry

Because semicircular cross-section solids are defined from a planar base, graphing the region or sketching a representative slice helps clarify the structure of the solid. Visualizing the diameter or radius at a point aids in identifying the correct radius function and verifying whether it aligns with the stated orientation.

The Role of the Base Region

The base region defines the geometry and limits of the semicircular slices. Students should identify whether the base provides:

A diameter, which must be halved to produce the radius.

A radius directly, usually from distance to an axis.

A difference between two curves, which becomes the diameter.

Understanding the base region ensures that the integrand in the definite integral reflects the exact area of each semicircle.

Building a Coherent Strategy for These Problems

Students benefit from a structured approach when evaluating volumes of solids with semicircular cross sections:

Identify the orientation of slices.

Determine bounds from the base region.

Express the radius function accurately.

Write the semicircle area formula using that radius.

Integrate the area function over the correct interval.

A consistent strategy reinforces understanding of how semicircular slices accumulate to produce a full three-dimensional volume through definite integration.

FAQ

Check how the problem describes the line segment that forms the cross section. If it specifies the entire distance across the semicircle, that is the diameter. If the distance is measured from a curve to an axis or from a line of symmetry, it is usually the radius.

If unsure, sketch the region and mark the slice perpendicular to the axis. Visual inspection often clarifies whether the segment spans the full width of the semicircle or only reaches its centre.

The semicircle area formula depends only on the square of the radius. When the radius comes directly from a single function or the difference of two functions, substituting into the area formula produces a straightforward polynomial or rational expression.

Other cross-sectional shapes, such as triangles or rectangles, may involve multiple geometric components, making their area expressions more complex.

Students sometimes choose bounds for the diameter rather than the axis of integration. The integral’s limits must reflect the variable along which slices are taken, not the size of each slice.

Also, when the base is defined by two curves, students may overlook intersection points. Always find where the bounding curves meet to ensure correct limits.

Switching the variable can change whether the radius is vertical or horizontal. This affects which functions define the diameter and how the radius is computed.

Integrating with respect to y can simplify problems where vertical slices create piecewise radii, or where the base is easier to describe using horizontal distances rather than vertical ones.

This happens when the diameter of the semicircle changes its defining expression at different positions along the axis.

Situations requiring this include:

• When two curves intersect within the interval, altering which function defines the diameter.

• When the base switches from a single function to a different boundary.

• When the geometry creates discontinuous or piecewise diameters across the domain.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis that are semicircles. The diameter of each semicircle extends from y = 0 to y = 4 − x on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 4.

(a) Write an expression for the radius of a typical cross section.

(b) Write, but do not evaluate, the integral that gives the volume of the solid.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

• Correct radius: (4 − x) / 2.

(b) 2 marks

• 1 mark for correct use of semicircle area formula: (1/2) pi r^2.

• 1 mark for complete integral with correct bounds:

Integral from 0 to 4 of (1/2) pi ((4 − x)/2)^2 dx.

Total: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A region in the xy-plane is bounded by the curves y = x, y = 0, and x = 2. A solid is formed by taking cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis that are semicircles whose diameters lie along the segment from the x-axis to the line y = x.

(a) State the length of the diameter of a cross section at a general position x.

(b) Write an expression for the radius of the cross section.

(c) Write the integral that represents the volume of the solid.

(d) Evaluate the integral to find the exact volume.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark

• States diameter length as x.

(b) 1 mark

• Radius given correctly as x / 2.

(c) 2 marks

• 1 mark for correct semicircle area formula expressed in terms of x.

• 1 mark for correct integral setup with correct bounds:

Integral from 0 to 2 of (1/2) pi (x / 2)^2 dx.

(d) 2 marks

• 1 mark for correct antiderivative.

• 1 mark for correct exact volume: pi/12.

Total: 6 marks.