AP Syllabus focus:

‘Some solids are defined using other geometric cross sections, where a known area formula in terms of a variable dimension is integrated to find total volume.’

Solids defined by varied geometric cross sections rely on expressing area formulas in terms of changing dimensions, allowing integration to accumulate volume across the chosen axis.

Understanding Solids with Other Geometric Cross Sections

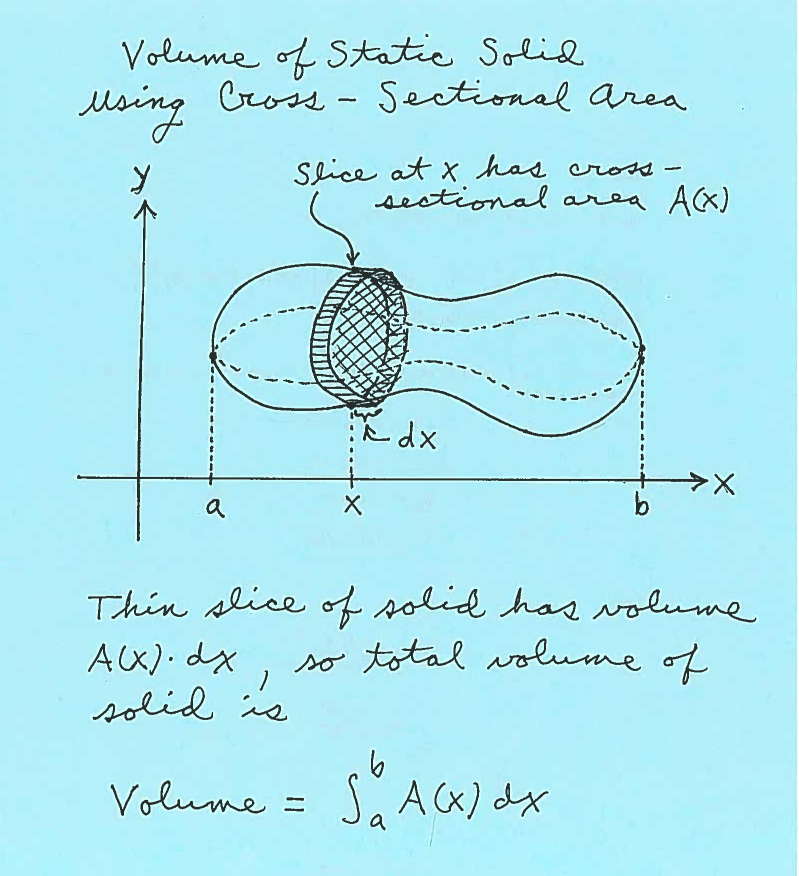

In many geometric-volume problems, a solid is constructed by specifying a base region in the coordinate plane and defining a cross-sectional shape perpendicular to an axis. The type of cross section determines the area expression, which then becomes the integrand in a volume integral. The key idea is that the solid’s volume emerges from the accumulation of infinitely many thin slices, each slice having area determined by the geometry of the cross-sectional shape.

This diagram shows a generic solid above the -axis with a representative slice of area and thickness . It illustrates how total volume is obtained by summing slice areas using the integral . The image aligns with AP Calculus AB expectations and introduces no content beyond the syllabus. Source.

When the cross sections are not squares, rectangles, triangles, or semicircles, the problem instead relies on any other known geometric area formula, provided the shape can be expressed using a dimension that varies as a function along the axis of integration. This approach maintains the standard structure of volume accumulation: find the shape’s area at position or , then integrate that area across the interval that defines the base.

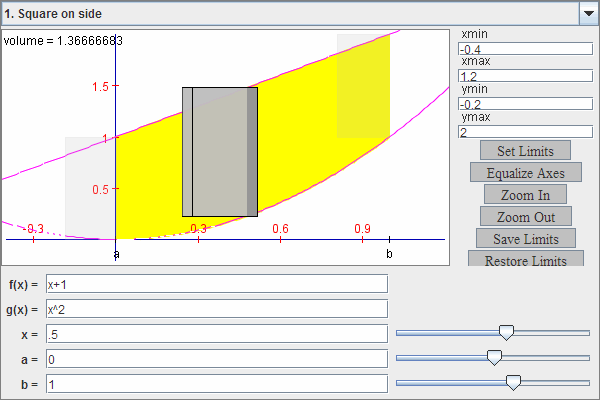

Expressing Cross Sections Using a Variable Dimension

The central quantity in these problems is a dimension function, often a side length, radius, or height, expressed in terms of the variable of integration. As the variable moves from one endpoint of the base region to the other, this dimension changes and determines the size of each slice.

Dimension Function: A function expressing a geometric length (such as a radius, side, or diagonal) in terms of or , used to compute the area of a varying cross section.

Once a dimension function is identified, it can be substituted into the area formula for the given cross section.

This figure shows a region between two graphs in the -plane serving as the base of a solid, with a square cross section rising vertically. It illustrates how a side length depends on , yielding a slice area for integration. The image includes specific functions such as and , adding context while remaining within AP Calculus AB expectations. Source.

The choice of orientation—integrating with respect to or —must match how the cross sections are described. If the problem states that cross sections are perpendicular to the -axis, then the area formula must use dimensions expressed as functions of .

Using Area Formulas to Build the Volume Integrand

Cross-sectional shapes may include familiar geometric figures whose area formulas depend on a single changing dimension. As long as the area formula can be written with one variable dimension, it is suitable for a cross-sectional volume problem.

Common possibilities include:

Equilateral triangles, where the area uses one side length.

Isosceles or right triangles, defined by a base or height varying with the coordinate.

Regular polygons, in which side length may be determined from the base region.

Ellipses, where the semi-major and semi-minor axes may depend on the coordinate.

Trapezoids, whose parallel sides could be determined by curve values at each coordinate.

Each area formula must be rewritten to include the dimension function corresponding to the slice’s location. Although students are not required to memorize obscure formulas, AP Calculus AB expects comfort applying standard geometric relationships once the relevant dimension is identified.

A single equation supports the construction of all such volume integrals.

= volume of the solid

= area of the cross section at position

= endpoints of the interval defining the base

This formula expresses the fundamental idea that volume is accumulated area. When the cross sections are perpendicular to the -axis, an analogous formula uses and instead.

Between equation usage and geometric interpretation, students must ensure that the area expression is always nonnegative, as area represents the physical size of each slice of the solid.

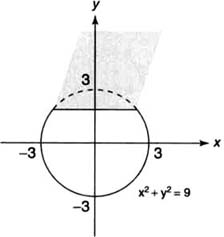

Identifying the Base Region and Interval of Integration

Every cross-sectional volume problem begins by identifying the base region in the coordinate plane.

This diagram presents a circular base defined by with a square cross section standing across the diameter. It highlights how the base determines the variable side length and thus the cross-sectional area for integration. The circle-and-square configuration adds contextual detail without exceeding AP Calculus AB requirements. Source.

The boundaries of this region determine the interval for integration. The base may be defined by:

A pair of curves bounding the region vertically or horizontally.

A single curve and an axis.

A polygonal or irregular region described in the problem.

Once the base is known, determine the direction in which the solid is sliced. If the problem states cross sections are perpendicular to the -axis, integrate with respect to ; if perpendicular to the -axis, integrate with respect to .

The interval of integration must exactly match the projection of the base region onto the axis of integration. This ensures that each slice corresponds to a valid cross section of the solid.

Process for Constructing Volume Integrals with Other Cross Sections

Students can use the following structured approach to set up volume integrals:

Identify the base region and determine the correct bounds for integration.

Determine the axis to which the cross sections are perpendicular.

Express the required geometric dimension (such as side length or radius) as a function of the integration variable.

Substitute the dimension function into the appropriate area formula.

Write the integrand as the area of one slice and integrate it over the interval.

This method ensures that any solid with a known cross-sectional shape can be described and analyzed using definite integrals.

Interpreting the Role of Geometry in Cross-Sectional Volumes

In these problems, geometry drives the construction of the integrand. The variable dimension controls the shape’s size at each position, and the known area formula translates that dimension into a slice area. Integration then accumulates these areas to produce the volume. This maintains the syllabus emphasis on viewing volume as accumulated area, even when the cross sections involve less common geometric figures.

FAQ

You must rewrite the area formula whenever the shape’s standard formula uses dimensions not directly given by the problem. This typically happens when the base provides a length, radius, or diagonal indirectly through curves.

Check whether the geometric dimension depends on x or y. If it changes along the axis of integration, substitute an expression involving the variable into the relevant area formula.

Common examples include polygons whose side lengths come from distances between curves, or shapes like ellipses where axes lengths depend on function values.

Yes, a cross section can be made of multiple geometric figures, provided each component has a known area formula.

To set up the integrand:

• Express each sub-area in terms of the dimension function.

• Add all sub-areas to form the total A(x) or A(y).

• Integrate this combined expression across the correct bounds.

This approach is valid as long as all parts of the slice can be written using a single variable.

A single integral cannot represent such a solid because the integrand would no longer give the correct area everywhere.

Instead:

• Split the base region into intervals where the cross-sectional shape is consistent.

• Write a separate definite integral for each interval.

• Add the integrals to obtain the total volume.

This ensures each integral corresponds to a well-defined area formula.

The bounds must still match the exact x- or y-values where the region begins and ends, even if these values come from solving non-polynomial equations.

If exact solutions exist (e.g., logarithmic or exponential intersections), use them directly.

If not, a problem may state approximate bounds or require you to leave the limits in symbolic form. AP exam questions will not require solving unsolvable intersections.

Examine how the dimension of the cross section is determined from the base.

Choose the orientation that gives the dimension as a single function:

• If the dimension is a vertical distance, integrating with respect to x is usually simpler.

• If it is a horizontal distance, integrating with respect to y is typically easier.

A good check: the area expression should involve one variable without requiring piecewise definitions whenever possible.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has a base in the xy-plane bounded by the curves y = 0, y = 2, and x = 4. Cross sections perpendicular to the y-axis are rectangles whose heights are given by h(y) = 3y and whose widths extend from x = 0 to x = 4.

(a) Write an expression for the area A(y) of a single cross section.

(b) Write, but do not evaluate, the definite integral representing the volume of the solid.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: Correct area expression.

• A(y) = height × width = 3y × 4

• Accept A(y) = 12y for full credit.

(b) 1–2 marks: Correct volume integral.

• 1 mark for correct limits (0 to 2).

• 1 mark for correct integrand: ∫ from 0 to 2 of 12y dy.

Total: 2–3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A solid has a base in the xy-plane bounded by the curve y = 9 − x2 and the x-axis. Cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis are isosceles right triangles with their legs lying in the base region.

(a) Express the side length s(x) of a triangular cross section in terms of x.

(b) Write an expression for the area A(x) of one cross section.

(c) Set up, but do not evaluate, the definite integral representing the volume of the solid.

(d) State whether the cross sections are taken with respect to x or y, and justify your answer.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark: Correct side length.

• s(x) = 9 − x2, since the leg of each triangle spans from the x-axis to the curve.

(b) 1–2 marks: Correct area formula for an isosceles right triangle.

• 1 mark for recognising area = (1/2) s2.

• 1 mark for substituting correctly: A(x) = (1/2)(9 − x2)2.

(c) 1–2 marks: Correct integral for volume.

• 1 mark for correct bounds (−3 to 3).

• 1 mark for correct integrand: ∫ from −3 to 3 of (1/2)(9 − x2)2 dx.

(d) 1 mark: Correct orientation and justification.

• Cross sections are taken with respect to x because the triangles are perpendicular to the x-axis.

Total: 4–6 marks.