AP Syllabus focus:

‘Volumes with known cross sections are understood as accumulation of cross-sectional areas, using definite integrals to sum infinitely many thin slices of the solid.’

Understanding volume through accumulated area provides a unifying perspective on solids with known cross sections, showing how integration aggregates infinitesimally thin slices into a complete three-dimensional solid.

Viewing Volume as Accumulated Area

In many geometric and applied contexts, a solid can be described by analyzing how its cross-sectional area changes along an axis. A cross section is a two-dimensional slice of the solid, usually taken perpendicular to either the -axis or the -axis.

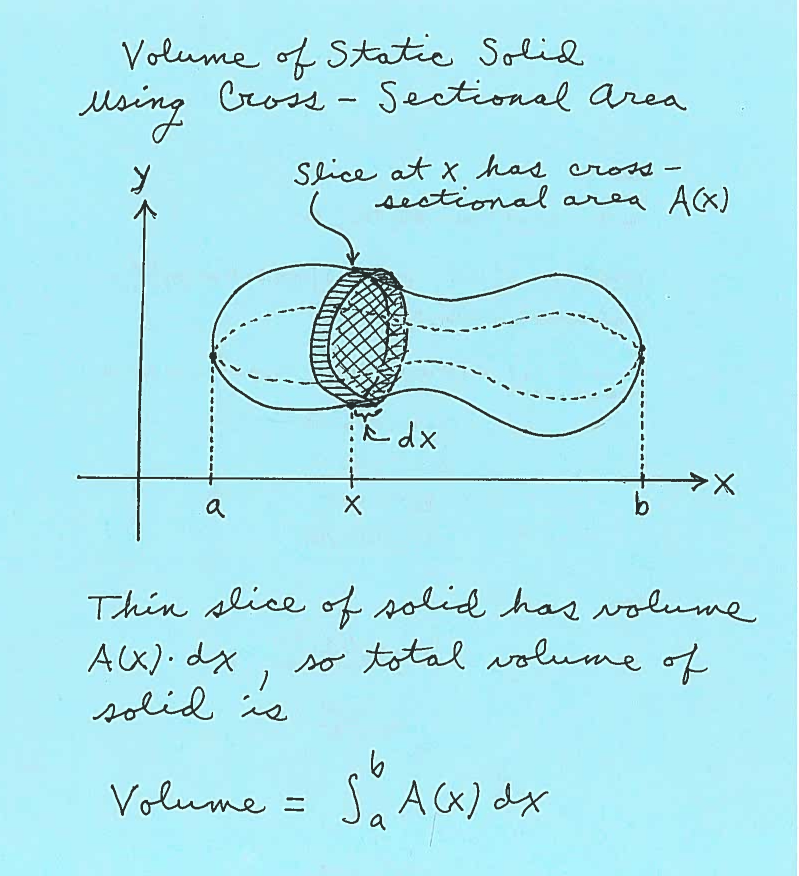

This diagram illustrates a solid above the -axis with a typical slice at position having area and infinitesimal thickness . Thinking of the volume as the sum of these tiny slices leads to the integral . The image reflects the AP idea that volume is an accumulation of cross-sectional areas along an interval. Source.

The central idea of this subsubtopic is that the volume of the solid is the accumulation of these areas, summed continuously through a definite integral.

When a cross-sectional area varies with position, we interpret volume as accumulated change in the same way integrals measure accumulated distance or accumulated net change. This connection reinforces the AP Calculus AB perspective that definite integrals express total quantities built from infinitesimal contributions.

The Role of the Area Function

If the area of a cross section at location is represented by a function , then the definite integral of over an interval gives the volume of the solid.

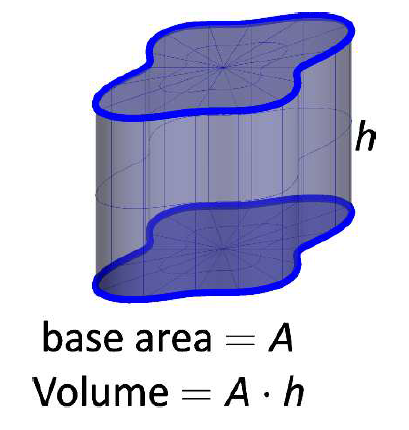

This figure shows a right cylinder whose volume is computed as area of the base times its height. It demonstrates the simplest case of viewing volume as cross-sectional area multiplied by thickness, which generalizes to the integral when the area varies. The cylinder is a specific example, but the underlying accumulation idea applies to all solids with known cross sections. Source.

This representation emphasizes that every slice contributes a small amount of volume that builds toward the total.

= Total volume of the solid (cubic units)

= Cross-sectional area as a function of (square units)

= Bounds of the interval along the axis of accumulation

This formulation relies on understanding that each slice is treated as having an infinitesimal thickness , enabling the integral to sum continuously across the domain. The definite integral becomes a natural mathematical expression of the idea that volume arises from stacking infinitely many very thin slices whose areas vary smoothly.

Interpreting Accumulation in Cross-Sectional Volume

The phrase accumulated area refers to the idea that each slice contributes only a small part of the total volume, but the integral aggregates these parts without missing any detail in the shape of the solid. This view is consistent with the AP requirement that students interpret integrals as measurements of accumulated change, here applied directly to geometric volume.

Because volume depends on area, and area depends on the geometry of the cross section, students must understand how the solid is generated. A base region in the plane typically defines the width or radius of each slice, and the known cross-sectional shape—such as a square, rectangle, triangle, or semicircle—determines the area formula. The area formula is then expressed in terms of or , depending on orientation.

A normal sentence explaining the importance of orientation ensures the correct choice of variable when writing the integral.

Orientation and Choice of Variable

A solid may be defined so that its cross sections are perpendicular to either the -axis or the -axis. The variable of integration should match the direction of slice accumulation:

Perpendicular to the -axis: Cross sections are functions of , and volume is expressed using .

Perpendicular to the -axis: Cross sections are functions of , and volume is expressed using .

The choice of orientation depends on which axis allows the cross-sectional dimensions to be expressed more simply. AP Calculus AB students are expected to interpret the geometric description, determine which orientation provides a clearer area function, and then represent the accumulated volume with an appropriate definite integral.

Understanding the Base Region’s Role

The base region anchors the geometry of the solid. Although volume is determined by cross-sectional area, the base region identifies where slices begin and end, and provides the measurements needed to determine side lengths, radii, or widths used in the area function. The interplay between the base and cross sections reinforces that a three-dimensional solid can be analyzed systematically through two-dimensional components.

Base Region: The planar region over which the solid extends and from which the dimensions of each cross section are determined.

A base region might be a bounded region in the -plane, the interval between two curves, or the area between a function and an axis. The definite integral uses the limits that correspond to the edges of this region.

A normal sentence ensures clarity before the next structured content.

Conceptualizing the Solid as a Sum of Slices

Viewing volume as the accumulation of area helps students visualize how three-dimensional objects relate to functions and integrals. Because the cross-sectional approach generalizes across many shapes, it allows the same strategy to be applied to varied solids:

Solids with constant cross sections

Solids with increasing or decreasing cross sections

Solids whose base shapes change geometry along the interval

Solids where formulas involve radii, widths, or other dimensions derived from given functions

This approach also emphasizes that the definite integral is not merely a computational tool but a conceptual representation of accumulation. It connects closely to earlier ideas from the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, where integrating a rate yields a total accumulated quantity.

Linking Cross Sections to Accumulated Volume

To represent volume effectively:

Identify the axis perpendicular to the cross sections.

Describe the geometry of each slice using the base region.

Find the area formula for the cross section in terms of the chosen variable.

Write a definite integral that accumulates this area across the interval.

This perspective aligns directly with the AP specification, which highlights that volumes with known cross sections are understood as the accumulation of cross-sectional areas, using definite integrals to sum slices and fully determine the solid’s volume.

FAQ

A solid is suited to the cross-sectional method when its slices are explicitly described by a known geometric shape, and no rotation around an axis is mentioned.

Typical indicators include:

• The problem defines the shape of each slice directly.

• The base region is given, but no axis of rotation is specified.

• The slice shape changes with position but does not arise from revolving a curve.

This method is especially appropriate when rotation-based radii would be awkward or impossible to define.

The ease depends on how the base region is described.

If boundaries of the region are given as x-functions, then using cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis makes it straightforward to determine widths or radii.

Conversely, if boundaries are expressed as y-functions, cross sections perpendicular to the y-axis avoid unnecessary algebraic manipulation.

Selecting the variable that yields simpler expressions helps reduce errors and integration difficulty.

Typical AP shapes include squares, rectangles, semicircles, and triangles.

These are used because:

• Their area formulas are simple.

• The side length or radius can be tied directly to distances in the base region.

• They allow clean translation from geometry to an area function A(x) or A(y).

More exotic shapes rarely appear because their area formulas would overshadow the calculus focus of the question.

The slice thickness represents an infinitesimally small change in the variable of integration.

When accumulating volume:

• Each slice contributes area multiplied by a tiny thickness.

• The integral acts as the limit of summing these contributions over the interval.

• The idea mirrors how distance accumulates from small velocity increments.

This interpretation reinforces the idea that integration measures total change built from infinitesimal pieces.

Yes, some solids may have piecewise-defined cross-sectional shapes.

In such cases:

• The interval is divided into regions where the slice shape is consistent.

• A separate area function is written for each subinterval.

• The total volume is found by summing the integrals across these intervals.

This structure mirrors the approach used when functions change behaviour across different domains.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis. At each value of x between x = 0 and x = 5, the cross-sectional area is A(x) = 4 + x square units.

Find the volume of the solid.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Substitutes A(x) = 4 + x into the volume expression V = integral from 0 to 5 of A(x) dx.

• 1 mark: Integrates correctly to obtain 4x + x^2/2.

• 1 mark: Evaluates the definite integral correctly to obtain 27.5 cubic units (or 55/2).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A solid has a base in the xy-plane bounded by the curves y = 0, y = 3, and x = 2. The cross sections perpendicular to the y-axis are squares.

(a) Write an expression for the side length of a typical square cross section at a value of y.

(b) Hence write a definite integral that represents the volume of the solid.

(c) Evaluate the integral to find the exact volume.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly states that the side length of the square is given by the horizontal distance from x = 0 to x = 2, so side length = 2.

• 1 mark: Recognises that area of each cross section is 4 (since it is a square with side length 2).

• 1 mark: Sets up the volume using V = integral from y = 0 to y = 3 of 4 dy.

• 1 mark: Attempts to evaluate the integral.

• 1 mark: Completes the evaluation to obtain volume = 12 cubic units.