AP Syllabus focus:

‘For revolution about the x- or y-axis, students write the radius of each disc as a function of the variable and use V = ∫ π(radius)² dx or dy to find volume.’

The disc method provides a powerful way to compute volumes of solids of revolution by accumulating circular slices whose radii depend on the axis of rotation.

Disc Method Formulas for Principal Axes

Understanding Solids of Revolution

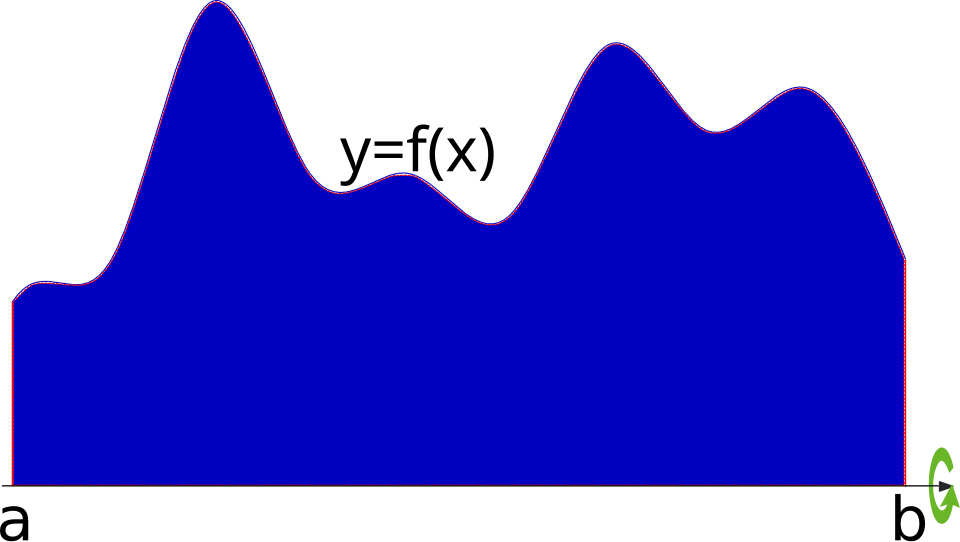

A solid of revolution is generated when a plane region is rotated around a principal coordinate axis. When revolving around the x-axis or y-axis, the resulting solid has circular cross sections that naturally lead to the disc method. These cross sections behave like a stack of thin discs whose combined volume models the entire solid.

When a region between a graph and an axis is revolved around that axis, it generates a solid of revolution whose cross-sections perpendicular to the axis are circular discs.

Illustration of a region under a curve rotated around a horizontal axis, generating a solid of revolution. The two-dimensional region and resulting three-dimensional solid are shown to highlight how rotation produces circular cross-sections. Specific function values are incidental to the concept being demonstrated. Source.

Identifying the Radius of a Disc

The radius of each disc is determined by the distance from the curve being revolved to the axis of rotation. This distance varies along the axis and must be expressed as a function of the independent variable. Students must ensure the radius corresponds to the function value measured perpendicularly from the axis.

Radius of Revolution: The perpendicular distance from the graph of a function to the axis about which the region is revolved.

This radius serves as the essential geometric link between the function and the geometry of the resulting solid.

Formula for Volume by the Disc Method

The disc method relies on the idea that small slices of thickness or can be approximated as discs whose areas accumulate into the total volume. Each disc has an area expressed in terms of its radius, and the integral sums all discs from one boundary of the region to the other.

= Radius as a function of , measured from the curve to the axis of revolution

A sentence explaining the connection: This formulation applies when the solid is generated by revolving a region around the x-axis, using horizontal slices.

= Radius as a function of , measured from the curve to the axis of revolution

This second form allows the use of vertical revolution around the y-axis, integrating with respect to .

Choosing Whether to Integrate with Respect to x or y

When the axis of revolution is the x-axis, it is common to integrate with respect to , because the resulting discs are oriented perpendicular to that axis. Conversely, rotation around the y-axis often favors integration with respect to . Students should check whether expressing the radius as a function of or leads to simpler expressions and limits.

Key considerations include:

Whether the given function is naturally expressed as or .

Which variable provides continuous, nonoverlapping radii formulae across the interval.

Whether the region’s boundaries are easier to describe horizontally or vertically.

Intervals of Integration

The limits of integration correspond to the span of the region along the axis of integration. Identifying these limits correctly is essential because the definite integral accumulates disc volumes only within the designated interval.

Students can determine limits by:

Reading interval endpoints directly from the problem statement.

Finding intersection points if the region is enclosed by multiple functions.

Confirming that the chosen limits match the axis of integration.

Visualizing Disc Accumulation

Visual interpretation strengthens understanding of why the disc method works. A solid of revolution is composed of infinitely many discs whose thickness approaches zero. As the thickness becomes infinitesimal, the area formula for a disc becomes an accurate representation of the cross section at each position.

Important visualization ideas include:

Cross-sectional area is always .

The radius changes continuously with or .

The axis of revolution dictates which variable controls the radius.

When the Disc Method Applies

The disc method should be used when the rotated region produces a solid without cavities. If the region does include a hole, the washer method is necessary instead, but that belongs to another subsubtopic. For this subsubtopic, the focus remains on solid discs with no missing interior.

Situations appropriate for the disc method:

Revolving a region bounded by a function and an axis.

Creating a solid where cross sections perpendicular to the axis are perfect circles.

Determining volume when only one function determines the radius at each slice.

Structuring Disc Method Problems

Students can streamline their process by following a structured approach:

Identify the axis of revolution (x-axis or y-axis).

Express the radius as a function of the appropriate variable.

Determine the interval of integration, ensuring alignment with the axis.

Write the volume integral in the correct form.

Evaluate or simplify the integral as necessary.

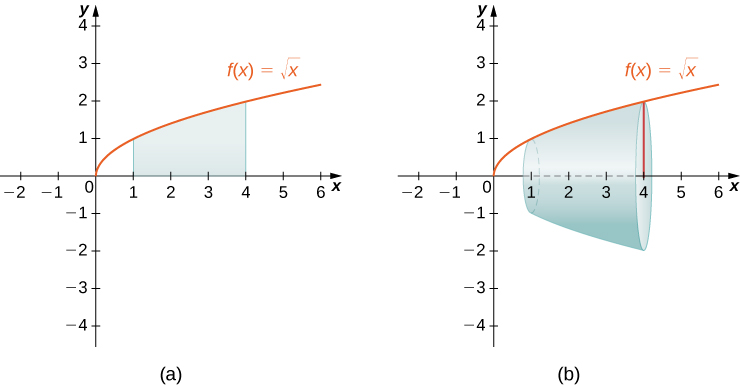

For rotation about the x-axis, we take vertical slices so that each slice forms a solid circular disc whose radius is given by the function value .

Region under on and the resulting solid of revolution about the -axis. The diagram shows how vertical rectangles sweep out discs when rotated and how the radius equals . The function and interval are specific examples, but the essential concept is the relationship . Source.

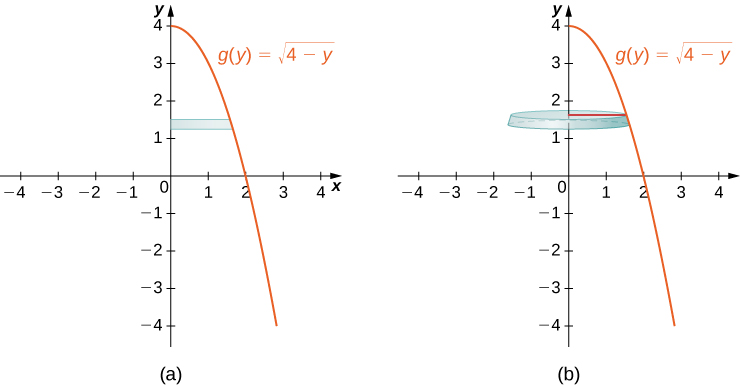

For rotation about the y-axis, we instead take horizontal slices that form discs whose radius is expressed as a function of , written .

Diagram of showing a horizontal rectangle that forms a disc when rotated around the -axis. The image emphasizes that horizontal slices create circular discs whose radii depend on . The specific function is an example, while the core idea is that for revolution about the -axis. Source.

Importance of Correct Radius Expressions

The radius must always represent a distance to the axis, not merely a function value. Students must visualize the geometry carefully to confirm that the radius function reflects the perpendicular line segment from the curve to the axis.

Using accurate radii ensures that the calculated volume is correct, since errors in radius measurement propagate as squared errors inside the integral.

FAQ

The disc method is most efficient when the region touches the axis of rotation directly, creating circular cross-sections with no inner radius.

You can confirm this by checking:

Whether the boundary curve lies on the axis being used for rotation.

Whether each perpendicular slice produces a full disc rather than a ring.

If both conditions hold, the disc method avoids unnecessary algebra and simplifies the integral.

The radius must correspond to the perpendicular distance between the curve and the axis because the area of each disc depends on that distance alone.

Using anything other than a true perpendicular distance produces an incorrect cross-sectional area, leading to significant errors in the computed volume.

If the function crosses the axis of rotation, the disc method no longer applies directly, because discs would sometimes have zero radius and sometimes negative implied radius.

In such cases:

Split the interval at the point where the graph meets the axis.

Treat each part separately, verifying whether discs or washers apply.

This ensures the radius is always a non-negative distance.

Yes, provided you can express the radius as a distance to the axis in terms of the variable of integration.

For parametric curves:

Express x or y in terms of the parameter, then relate the radius to the chosen axis.

For implicit curves:

Solve for y as a function of x, or x as a function of y, in a region where the relationship behaves nicely.

Your choice determines whether slices are vertical or horizontal, which can simplify or complicate the radius expression.

Integrating with respect to:

x is usually simpler when the function is given in the form y = f(x).

y is advantageous when the region is bounded more naturally by x expressed as a function of y.

Selecting the variable that avoids inverse functions often yields a cleaner integral.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A region in the first quadrant is bounded by the curve y = 2x, the x-axis, and the vertical line x = 3. The region is revolved about the x-axis to form a solid of revolution.

(a) Write down the integral expression for the volume of the solid using the disc method.

(b) State the radius of a typical disc in terms of x.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark for writing the correct integral setup.

Answer: V = integral from x = 0 to x = 3 of pi multiplied by (2x) squared dx.

(b) 1 mark for identifying the radius.

Answer: Radius = 2x.

Maximum: 2 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function f is defined by f(x) = 4 − x for 0 ≤ x ≤ 4. The region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis, and the line x = 4 is revolved about the x-axis.

(a) Write the integral expression for the volume of the solid formed.

(b) Explain why the disc method is appropriate in this situation.

(c) Evaluate the volume of the solid.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark for correct volume integral.

Answer: V = integral from x = 0 to x = 4 of pi multiplied by (4 − x) squared dx.

(b) 1 mark for explanation that the cross-sections perpendicular to the axis of rotation are solid discs, not washers, because the region touches the axis.

(c) 1 mark for correct expansion of (4 − x) squared,

1 mark for correct antiderivative,

1 mark for correct numerical volume.

Correct final answer: 64 pi divided by 3.

Maximum: 5 marks.