AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students identify the interval of revolution, express radius in terms of x or y, set up the definite integral using the disc method, and evaluate or approximate the volume.’

The disc method provides a powerful way to compute volumes of solids of revolution by accumulating infinitely thin circular slices whose radii depend on the generating curve.

Setting Up Disc Method Integrals

Understanding how to set up disc method integrals requires recognizing how a region generates a solid when revolved around an axis. The disc method uses circular cross sections perpendicular to the axis of revolution, and the volume arises from integrating their areas. When a function or geometric boundary is revolved, each cross section forms a disc whose radius is determined by its distance to the axis.

Identifying the Interval of Revolution

The first step is identifying the interval of revolution, the domain over which the region is swept around the axis. This interval corresponds directly to the variable of integration.

When revolving around the x-axis, slices are perpendicular to the x-axis, so the integral variable is x, and the interval is taken from the leftmost to the rightmost point of the region.

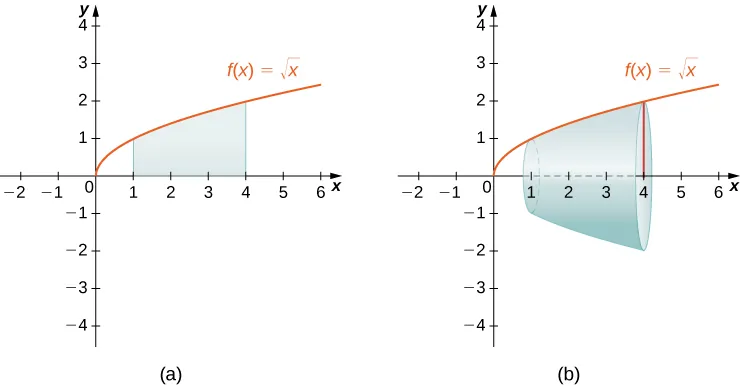

Region under on an interval and the solid formed when the region is revolved about the x-axis. The shaded rectangle in (a) becomes a circular disc in (b), illustrating how slices perpendicular to the x-axis generate the solid. The specific function and interval are incidental—the goal is understanding how discs relate to the disc method setup. Source.

When revolving around the y-axis, slices are perpendicular to the y-axis, so the integral variable is y, and the interval spans the lowest to highest y-values in the region.

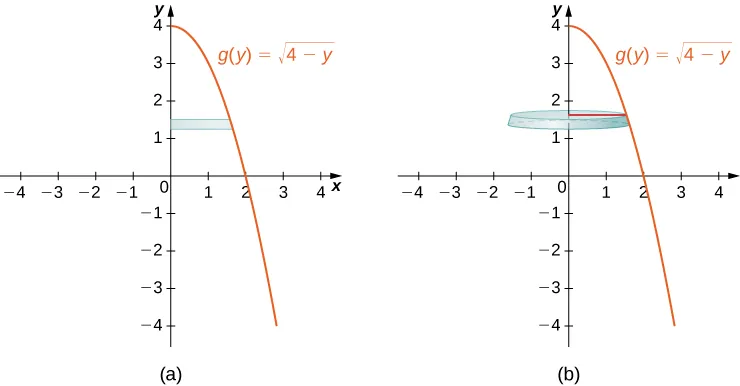

Region bounded by with a horizontal slice that forms a circular disc when revolved around the y-axis. The figure highlights that cross sections perpendicular to the y-axis are horizontal, so the radius is measured horizontally. The particular curve and numbers add extra detail, but the essential concept is how disc orientation determines the variable of integration. Source.

Careful attention to endpoints ensures the solid’s full extent is captured. Students should always confirm that the interval aligns with the orientation of the slices used in the method.

Expressing the Radius Function

The volume formula requires a radius function, defined as the distance from the curve to the axis of revolution. When a function is revolved around the x-axis, the radius is simply because the axis lies at . For other axes, the radius must be expressed more generally as a vertical or horizontal distance, depending on orientation.

Radius Function: The distance from a point on the generating curve to the axis of revolution, expressed as a function of the variable of integration.

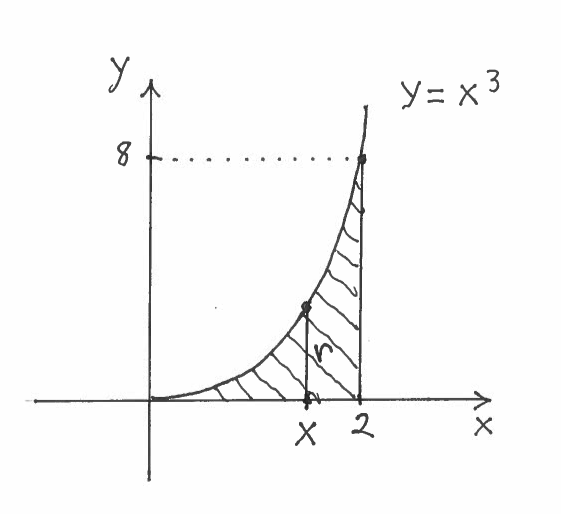

Region under with a vertical slice indicating the radius measured from the x-axis to the curve. This illustrates how the radius function corresponds to the height of the graph above the axis of revolution before applying the disc area formula . The labeled curve and endpoint values are extra details beyond syllabus requirements but effectively show the geometric meaning of the radius. Source.

Because the radius is squared in the disc area, correctly expressing this distance is essential for accurate volume computation. Errors in sign or orientation often lead to incorrect integrals, so students must visualize the distance carefully.

The Disc Method Formula

Once the radius is known, the cross-sectional area of each disc is . Integrating this area along the axis of revolution produces the volume. This structure reflects the idea of volume as “accumulated area,” with each slice contributing a differential amount of volume.

= Radius function, representing distance from curve to axis

= Integration variable determined by orientation (x or y)

Before evaluating, students should verify that the radius uses the correct axis and that the integration bounds match the axis of revolution. This prevents mixing inconsistent orientations, a common issue for early learners.

Structuring the Setup Process

Setting up a disc method integral can be viewed as a structured multistep procedure. Each step ensures that the resulting integral correctly represents the solid.

Determine orientation

Decide whether the revolution is around a horizontal or vertical axis to select the correct integration variable.Identify the interval of revolution

Establish limits corresponding to the smallest and largest values of the integration variable.Express the radius function

Distinguish whether the distance to the axis is vertical or horizontal to form or .Write the area expression

Use the disc area formula with the chosen variable.Set up the definite integral

Combine the area and interval into a single integral representing accumulated disc volumes.Evaluate or approximate

Apply antiderivatives or numerical methods to obtain the solid's volume.

These steps reinforce the conceptual framework of the method, ensuring consistency across varied problems.

Evaluating or Approximating Disc Integrals

After constructing the integral, students apply standard integration techniques to compute volume. For many solids formed by simple functions, evaluation involves basic antiderivatives. However, not all radius functions yield elementary antiderivatives, so approximation may be required using numerical integration, depending on the context.

When approximating, students should remember that the definite integral still represents accumulated disc areas; the method of accumulation does not change. Only the computation technique varies. Understanding this makes numerical techniques feel like a natural extension of the disc method’s structure.

Common Considerations When Setting Up Integrals

Several conceptual nuances improve accuracy when applying the disc method:

Axis of revolution dominates setup; always visualize the solid to avoid incorrect radii.

Radius must always be nonnegative, as it represents geometric distance.

Function orientation matters; if the radius depends on horizontal distance, express functions in terms of y instead of forcing an x-based formula.

The disc method applies only when cross sections are solid discs, not washers; if a hole exists, the washer method must be used instead.

These considerations ensure the integral represents the geometry faithfully, aligning with the AP goal of viewing volume as accumulation of circular slices.

Integrating Graphical and Algebraic Information

Students often encounter problems involving graphs or mixed representations. In these cases, the radius function must be inferred visually, and the interval may depend on intersection points or boundaries read from the graph. The fundamental ideas remain unchanged: determine orientation, find limits, express radius, and integrate.

By consistently viewing the disc method as a process of translating geometric distances into an integral representing accumulated area, students build a reliable approach to setting up and evaluating disc method integrals, directly aligned with the AP Calculus AB specification.

FAQ

Choose slices that are perpendicular to the axis of revolution.

If revolving about the x-axis or any horizontal line, use vertical slices (integrate with respect to x).

If revolving about the y-axis or any vertical line, use horizontal slices (integrate with respect to y).

This choice ensures each slice forms a full disc without gaps or holes.

If the integral must be in terms of y, you may need to express x as a function of y. This occurs when slices are horizontal.

Rewriting ensures the radius is expressed using the correct variable and avoids mixing x and y in a single integral.

Focus on the distance between the curve and the axis of revolution.

Useful checks include:

• Draw a thin slice first, then trace a perpendicular line to the axis.

• Mark the radius directly on the diagram.

• Verify that the radius is always non-negative across the interval.

Yes, provided the region touches the axis of revolution directly so that each cross section forms a solid disc.

If a top–bottom pair of curves creates a gap from the axis, then a washer or shell approach is required instead.

The key question is whether the slice has an inner radius greater than zero.

Volume must have units of length cubed.

Check that:

• The radius has units of length.

• The squared radius has units of length squared.

• Integrating with respect to a variable whose differential also has units of length produces length cubed.

This quick unit check helps catch common set-up errors such as using the wrong variable or an incorrect radius expression.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A region in the first quadrant is bounded by the curve y = 2x, the x-axis, and the vertical line x = 3.

This region is revolved about the x-axis to form a solid of revolution.

(a) Write down the definite integral representing the volume of the solid using the disc method.

(b) State the radius function used in the integral.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

• Correct volume integral: V = integral from 0 to 3 of pi multiplied by (2x) squared dx.

(b) 1 mark

• Correct radius function: r(x) = 2x.

Award a third mark if both parts are fully correct with clear notation.

Total: 2–3 marks depending on accuracy and clarity.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

The curve y = 4 − x squared is defined for x between 0 and 2. The region between this curve and the x-axis is revolved about the x-axis to produce a solid of revolution.

(a) Write down an expression for the radius of a typical disc at position x.

(b) Set up, but do not evaluate, the definite integral that represents the volume of the solid.

(c) Explain why the disc method is more appropriate than the washer method for this situation.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark

• Correct radius: r(x) = 4 − x squared.

(b) 2–3 marks

• Correct integrand: pi multiplied by (4 − x squared) squared. (1 mark)

• Correct limits 0 to 2. (1 mark)

• Full, correctly written integral statement. (1 mark)

(c) 1–2 marks

• States that the cross sections are solid discs because the region touches the axis of revolution with no gap or inner radius. (1 mark)

• Clearly explains that no hole is present, so the washer method is unnecessary. (1 additional mark)

Total: 4–6 marks depending on completeness and explanation quality.