AP Syllabus focus:

‘A solid of revolution is formed by revolving a region around the x- or y-axis; its volume can be found by accumulating circular discs of varying radius.’

Solids of revolution around the coordinate axes arise when a planar region is rotated about either the x-axis or y-axis, creating a three-dimensional solid whose volume is determined using definite integrals.

Understanding Solids of Revolution

A solid of revolution is generated when a two-dimensional region in the coordinate plane is rotated about a fixed axis. This rotation forms a three-dimensional object whose cross sections perpendicular to the axis of rotation are circles. Because these circular cross sections represent accumulated slices of volume, definite integrals provide the natural mathematical tool for determining total volume.

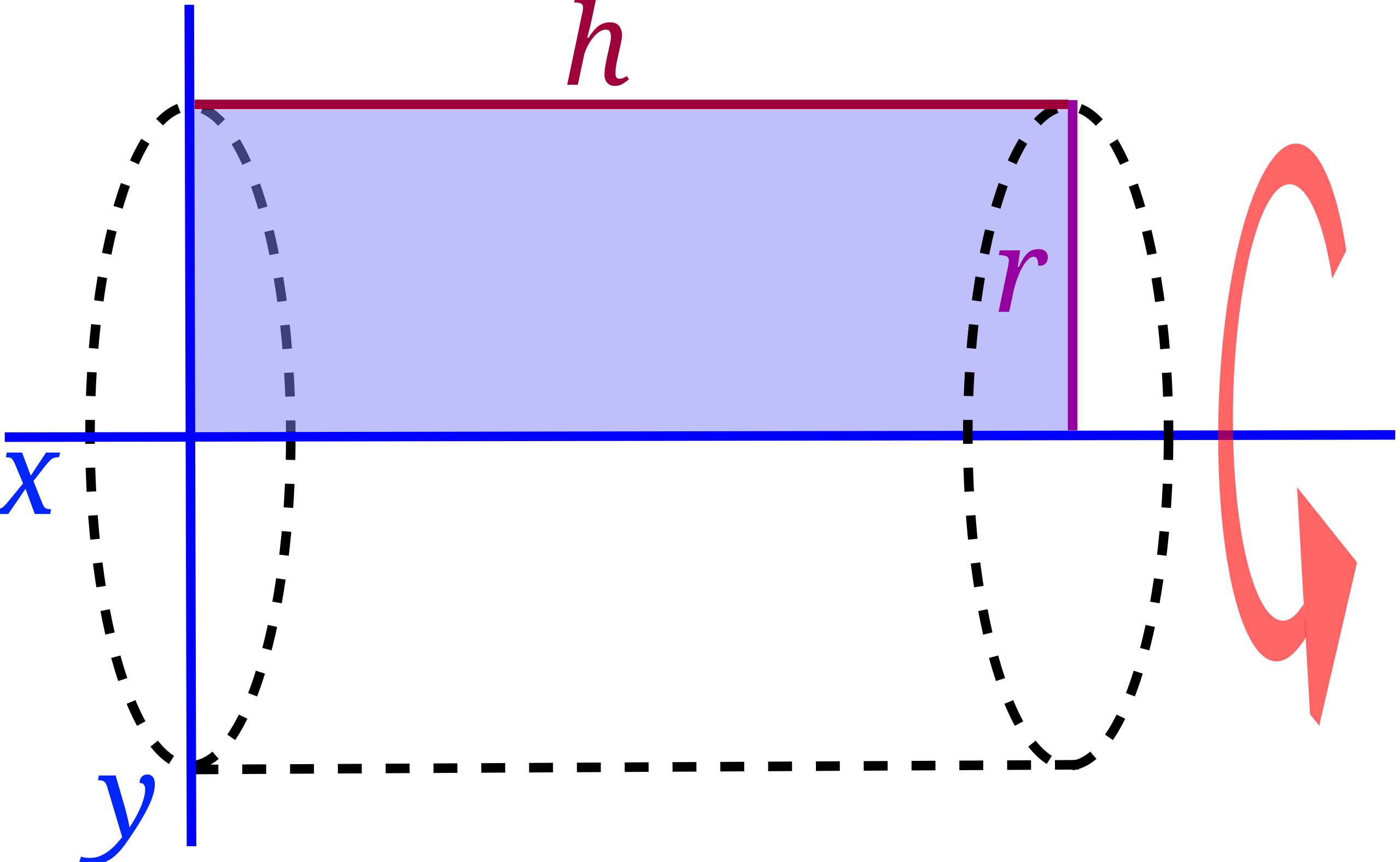

This diagram shows a rectangle of height and length being rotated about the -axis to form a right circular cylinder. The red arrow indicates the axis and direction of rotation, and the shaded rectangle represents the generating region in the plane. This connects the geometric formula to the idea of a solid of revolution formed from a planar region. Source.

The Role of Cross-Sectional Geometry

When a region is revolved around a coordinate axis, each perpendicular slice of the resulting solid becomes a disc, a circular slice whose radius depends on the distance from the curve to the axis. Before introducing formulas, it is helpful to understand what radius represents in this context. The radius at a particular point reflects how far the original graph lies from the chosen axis of revolution, making the radius a function of the independent variable.

Radius of Revolution: The distance from a point on the generating curve to the axis about which the region is revolved.

The radius changes as the function changes, meaning that accumulating discs with varying radii naturally requires integration.

A solid of revolution around the x-axis uses horizontal slicing, while rotation around the y-axis uses vertical slicing. The orientation must match the variable of integration to ensure that each cross section is perpendicular to the axis.

Generating Solids Around the x-Axis

Revolving a region around the x-axis creates discs stacked along the x-direction. The radius of each disc is determined by the vertical distance from the curve to the x-axis. If the function defining the boundary is , then the radius is simply . The method depends on interpreting the solid as an accumulation of circular slices, each contributing an incremental volume amount.

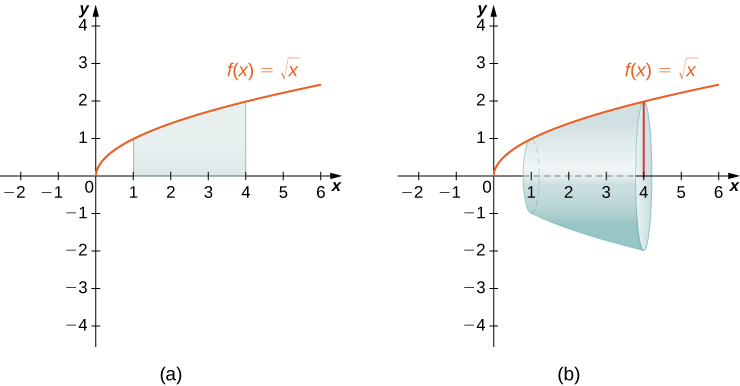

The left panel shows the region under above the -axis on , which serves as the generating region. The right panel shows the solid obtained when this region is revolved about the -axis, forming a shape whose cross sections perpendicular to the axis are circular discs. This visually supports the disc method formula without adding concepts beyond the AP syllabus. Source.

Disc Volume Through Integration

To determine the volume of the entire solid, the area of a representative disc is integrated across the interval where the solid is formed.

= Radius of the disc, measured from the curve to the x-axis

= Interval over which the region is revolved

The definite integral accumulates infinitely many disc areas, reflecting how rotation creates continuous three-dimensional volume from a continuous function.

Because discs are circular, using naturally incorporates the geometry of revolution. The process emphasizes interpreting volume as accumulated area, which aligns with the fundamental interpretation of definite integrals as total accumulated change.

Generating Solids Around the y-Axis

When revolving a region around the y-axis, the process is analogous, but the radius must be expressed using horizontal distance. In this case, the function is written in terms of as a function of , or the curve must be invertible so that the horizontal distance to the axis can be measured correctly.

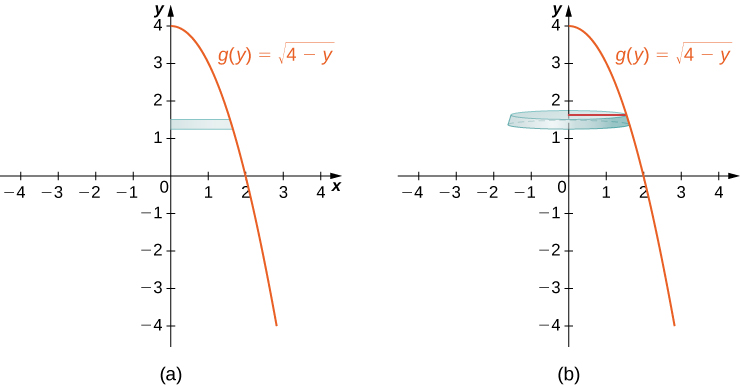

The left panel shows a thin horizontal rectangle between the curve and the -axis, representing a slice whose length is the disc radius. The right panel shows the corresponding horizontal disc produced by rotation about the -axis. The diagram emphasizes that for rotation around the -axis, the radius is a function of and volume is computed with . Source.

Understanding the Radius in y-Axis Rotation

Because each disc is perpendicular to the y-axis, its radius corresponds to the x-value of the bounding function. If the boundary is given as , then the radius is , and integration proceeds with respect to . The orientation must always match the axis of revolution so that each slice remains circular.

= Radius of the disc, measured horizontally from the curve to the y-axis

= Vertical interval defining the region being revolved

This formulation highlights that solids of revolution depend more on geometric orientation than on the specific algebraic form of the function. Identifying whether the radius is vertical or horizontal is essential for correctly setting up disc integrals.

A normal sentence must appear between boxed elements to satisfy formatting guidelines. In many problems, functions may need to be rewritten or interpreted graphically to express the radius appropriately.

Visualizing Accumulated Circular Slices

The concept of accumulated circular discs is foundational to understanding this subsubtopic. Each disc contributes a small volume slice, and the definite integral sums these contributions. The disc method appears whenever a region is revolved around a principal coordinate axis without creating a hollow center. Because the slices are solid discs rather than rings, no inner radius exists.

Key Features of Disc-Based Solids of Revolution

The following points summarize essential characteristics of solids formed using this method:

The cross sections perpendicular to the axis of rotation must be solid discs, not washers.

The radius is always measured directly from the generating curve to the axis of rotation.

The integral bounds correspond exactly to the interval defining the base region.

The integrand represents the area of each disc, which is always .

The method applies cleanly only when the entire region touches the axis of revolution without forming an inner cavity.

Importance in the AP Calculus AB Curriculum

This subsubtopic establishes the conceptual foundation for later work with washers and shells. Understanding rotation around the x- or y-axis is crucial because it introduces the geometric structure used throughout applications of integration. The emphasis on interpreting volume as an accumulation of area strengthens students’ conceptual understanding of definite integrals and reinforces the idea that integration unifies many geometric and physical problems by capturing continuous change.

FAQ

Use the disc method when the region touches the axis of revolution directly, so that each perpendicular slice forms a solid circular disc with no hollow centre.

Check the following:

• The axis of revolution must be the x-axis or y-axis.

• The curve must not create an inner gap between the region and the axis.

• All cross-sections perpendicular to the axis must be filled in completely.

If any hollow region appears, the washer method is required instead.

The radius of each disc changes depending on where you take the slice, so it must be written using the same variable that changes along the axis of rotation.

If you integrate with respect to x, the radius must be written using x; if you integrate with respect to y, the radius must be written using y. Otherwise, the radius does not correctly track the distance from the curve to the axis as you move along the solid.

Typical mistakes include:

• Mixing up horizontal and vertical distances when defining the radius.

• Using the top minus bottom idea from area-between-curves problems, which does not apply here.

• Forgetting to square the radius when substituting into the volume formula.

• Using incorrect interval limits, especially when switching variables to y.

Carefully sketching the region before beginning the setup helps prevent most of these mistakes.

A graph visually shows the perpendicular distance between the function and the axis, which is the radius of the disc.

From the graph, you can:

• Identify whether the radius should be vertical or horizontal.

• Determine if the region touches the axis or leaves a gap.

• See where the function intersects the axis to set bounds correctly.

Graphical insight often clarifies radius selection more effectively than algebra alone.

Yes. Rewriting the function can make the radius easier to express and the integral simpler to evaluate.

For rotation around the y-axis, rewriting x as a function of y avoids complicated inverse expressions.

A rewritten function may also simplify squaring the radius, which can reduce algebraic errors.

Choosing the clearer form of the function usually leads to a shorter and more accurate solution.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A region in the first quadrant is bounded above by the curve y = 3x, below by the x-axis, and to the right by x = 2. The region is revolved about the x-axis to form a solid of revolution.

Find the volume of the solid formed.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Substitute the radius function into the disc formula: volume = integral from 0 to 2 of pi(3x)^2 dx.

• 1 mark: Correct integration of 9x^2 to obtain 3x^3.

• 1 mark: Final answer: 24pi.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function is defined by y = 4 - x^2 for x between 0 and 2. The region bounded by the curve, the x-axis, and the y-axis is revolved about the y-axis to form a solid of revolution.

(a) Write an expression for the radius of a typical disc formed when the region is revolved about the y-axis.

(b) Show that the volume of the solid can be written as an integral with respect to y.

(c) Hence determine the exact volume of the solid.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Correct statement that the radius is the x-value expressed in terms of y.

• 1 mark: Correct rearrangement giving x = sqrt(4 - y).

(b)

• 1 mark: Correct structure of the volume integral: volume = integral of pi(radius)^2 dy.

• 1 mark: Correct limits: y from 0 to 4.

• 1 mark: Substitution of radius: integral from 0 to 4 of pi(4 - y) dy.

(c)

• 1 mark: Correct antiderivative of (4 - y) giving 4y - y^2/2.

• 1 mark: Correct evaluation at 0 and 4 leading to 8pi.