AP Syllabus focus:

‘Scales of analysis used by geographers include global, regional, national, and local levels for examining geographic issues.’

Geographers analyze phenomena at multiple scales to understand spatial patterns, reveal variation, and interpret processes. Each scale—global, regional, national, and local—offers distinct insights into geographic issues.

Levels of Geographic Scale

Geographic scale refers to the unit of analysis or the level at which geographic data and patterns are examined. Understanding scale is essential because patterns may appear differently depending on the level of observation.

Scale of Analysis: The level or scope at which geographic patterns and processes are examined, ranging from very broad (global) to very specific (local).

Geographers select a scale strategically, depending on the question they wish to answer, the type of data available, and the patterns they aim to uncover.

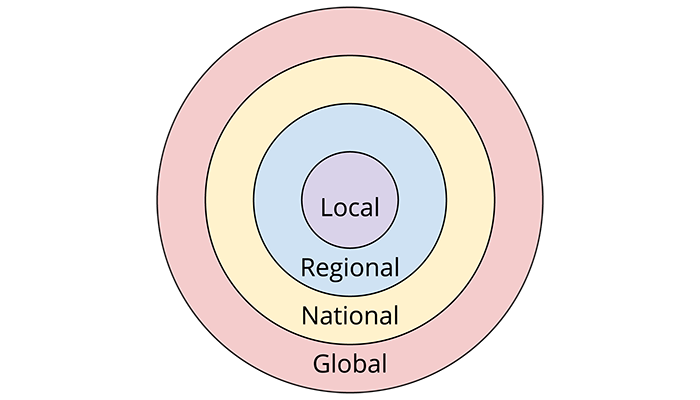

This diagram presents the four major geographic scales as nested circles, showing how local processes fit within regional, national, and global contexts. It reinforces the hierarchical nature of geographic analysis. The illustration includes no significant extra details beyond the content required by the syllabus. Source.

Global Scale

The global scale examines the Earth as a whole, focusing on worldwide processes, patterns, and relationships. At this level, the emphasis is on broad trends that transcend national borders.

Key Characteristics of the Global Scale

Worldwide patterns of cultural, economic, or environmental phenomena

Large data sets that generalize across continents and hemispheres

Connections and flows that link multiple world regions

Broad comparisons rather than fine-grained differences

Globalization: A process that creates increasing interconnections among people and places through economic, political, cultural, and technological exchanges.

The global scale is essential for understanding issues such as climate change, global supply chains, pandemic diffusion, and international migration flows.

Regional Scale

The regional scale focuses on areas larger than a single country but smaller than the entire world. A region may be defined by physical, cultural, economic, or political characteristics.

Types of Regions at the Regional Scale

World regions such as Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, or Southeast Asia

Functional regions such as economic zones or cultural spheres

Environmental regions such as biomes or climate zones

Analytical Uses of the Regional Scale

Revealing similarities among neighboring countries or areas

Identifying shared characteristics such as dominant languages, climates, or economic systems

Understanding interactions and flows that operate across multiple states

A regional perspective helps geographers examine spatial patterns that extend beyond national boundaries but remain more specific than global trends.

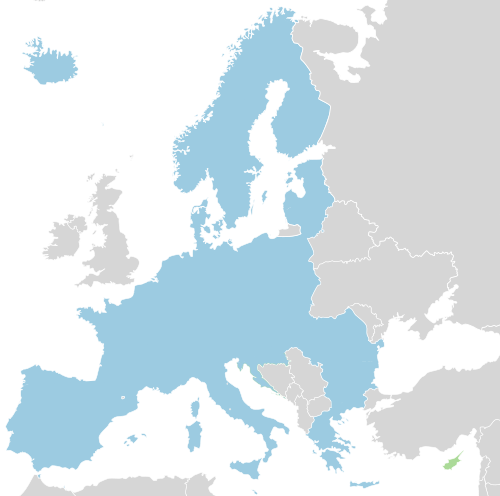

This map depicts the Schengen Area, illustrating how several nation-states can form a cohesive political region for analyzing mobility, policy, and interactions. It demonstrates the regional scale as an intermediate level of analysis. Some additional map distinctions appear, such as states legally required to join in the future, but these reinforce rather than distract from the core concept of regional organization. Source.

National Scale

The national scale examines patterns within the boundaries of a specific country. Governments, organizations, and researchers often use this scale to develop policies or analyze social and economic conditions.

Features of the National Scale

Uniform administrative boundaries and standardized data sets

Focus on country-level demographics, economies, and political structures

National policies and laws that shape patterns within the state

Comparisons between countries using standardized international metrics

Nation-State: A political unit in which the boundaries of a nation (a cultural group) align with the boundaries of a state (a political territory).

National-scale analysis is especially important for studying population trends, economic development, infrastructure, and public policy.

Local Scale

The local scale focuses on specific places such as cities, neighborhoods, or individual landscapes. This scale provides the most detailed resolution, revealing fine-grained variation hidden at broader levels.

Key Characteristics of the Local Scale

Highly detailed data, often field-collected or community-specific

Observation of micro-level patterns and spatial variability

Emphasis on individual behaviors, local decision-making, and distinct cultural landscapes

Ability to capture unique features of places, such as land use patterns or neighborhood identities

Cultural Landscape: The visible imprint of human activity on the environment, including buildings, roads, agricultural fields, and other human-made features.

The local scale is crucial for understanding spatial patterns like housing segregation, zoning decisions, local cultural practices, and land use changes.

Why Multiple Scales Matter

Geographers use multiple levels of scale because patterns and processes change depending on the scale at which they are observed. A trend that appears uniform globally may show significant diversity locally.

Key Insights of Multiscale Analysis

Patterns may be hidden, exaggerated, or reversed when shifting scales.

Different conclusions may emerge depending on the chosen scale.

Understanding scale prevents misinterpretation of data and spatial patterns.

Geographic issues often operate simultaneously at multiple scales.

Examples of How Scale Shapes Interpretation

A global decline in birth rates may mask significant national or local differences.

Regions may share similar climates but differ culturally or economically.

Local land use decisions can influence national environmental policies.

Global climate change is experienced differently at the regional, national, and local levels.

Using Scale in Geographic Inquiry

Geographers intentionally select a scale of analysis to frame research questions, interpret data, and draw conclusions. When analyzing a phenomenon, they often:

Identify the relevant scale or scales

Compare patterns across multiple levels

Relate local events to broader national, regional, or global processes

Evaluate how shifting scale alters interpretation

Choosing the appropriate level of scale helps geographers construct more accurate, nuanced understandings of spatial patterns and human–environment relationships.

FAQ

Geographers choose a scale based on the spatial extent of the phenomenon, data availability, and the level of detail needed to answer the research question.

They also consider whether analysing multiple scales will reveal hidden patterns. For example:

Global data may show broad trends.

National or local data may expose variation that changes the interpretation.

The choice of scale is therefore strategic, not fixed, and often involves comparing patterns across several scales.

Analysing a phenomenon at a scale that is too broad may obscure important differences. Local characteristics can disappear entirely when aggregated into national or regional figures.

Conversely, using a scale that is too narrow may exaggerate small differences and fail to show wider spatial trends.

This issue is known as the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP), where the scale or boundaries chosen affect the results

Local-scale data tend to be highly detailed and often collected directly by individuals, municipalities, or small organisations.

Common examples include:

Neighbourhood demographics

Land use surveys

Local transport patterns

Global-scale data, by contrast, are usually aggregated from national datasets or international organisations and represent broad patterns such as world population distribution or global climate trends.

National boundaries are legally defined and shape data collection, policy decisions, and administrative divisions. Statistics are typically standardised within these borders.

Regional boundaries, however, may be cultural, economic, or environmental rather than political. For example, a cultural region may cut across several states.

Because regional boundaries are more flexible, interpretations at this scale vary depending on how the region is defined.

They use a multiscalar approach that involves:

Reviewing available data for each relevant scale

Mapping or visualising the patterns

Identifying differences or consistencies across scales

Determining how each scale adds context to the overall understanding

This method helps geographers trace relationships from local processes to global trends, ensuring that insights are not restricted to a single level of analysis.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain the difference between the national scale and the regional scale in geographic analysis. Provide one example illustrating how a pattern may appear differently at each scale.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a correct distinction between national and regional scales (e.g., national refers to a single country; regional groups multiple countries or areas).

1 mark: Explains how scale affects geographic interpretation (e.g., broader similarities at regional level; more detailed variation at national level).

1 mark: Provides an appropriate example showing different patterns at the two scales (e.g., economic development appearing uniform regionally but varied nationally).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how examining a geographic issue at the global, national, and local scales can change the understanding of spatial patterns. Refer to one specific issue to support your answer.

Question 2

1 mark: Identifies that different scales reveal different levels of detail or variation.

1 mark: Describes how the global scale presents broad or generalised patterns.

1 mark: Describes how the national scale reveals variability between places within a country.

1 mark: Describes how the local scale provides fine-grained detail or distinct patterns not visible at broader scales.

1 mark: Clearly links the explanation to a named geographic issue (e.g., population change, climate impacts, migration).

1 mark: Provides a coherent, well-developed comparison showing how interpretations shift across the three scales.