AP Syllabus focus:

‘Contemporary and historical trends in population growth and decline can be explained by changes in fertility, mortality, and migration over time.’

Population growth and decline shift across history as fertility, mortality, and migration patterns evolve. Understanding these long-term demographic trends helps geographers analyze population change at multiple scales.

Trends in Population Growth and Decline Over Time

Contemporary and historical demographic trends reflect how fertility, mortality, and migration interact to reshape the size and composition of populations. These shifts occur gradually or rapidly depending on social, economic, political, technological, and environmental conditions influencing human behavior and well-being. Tracking these patterns across different eras allows geographers to interpret why populations expand, stabilize, or shrink.

Historical Shifts in Population Growth

Long-term transformations in global population growth have been driven mainly by declining mortality rates combined with varying fertility patterns.

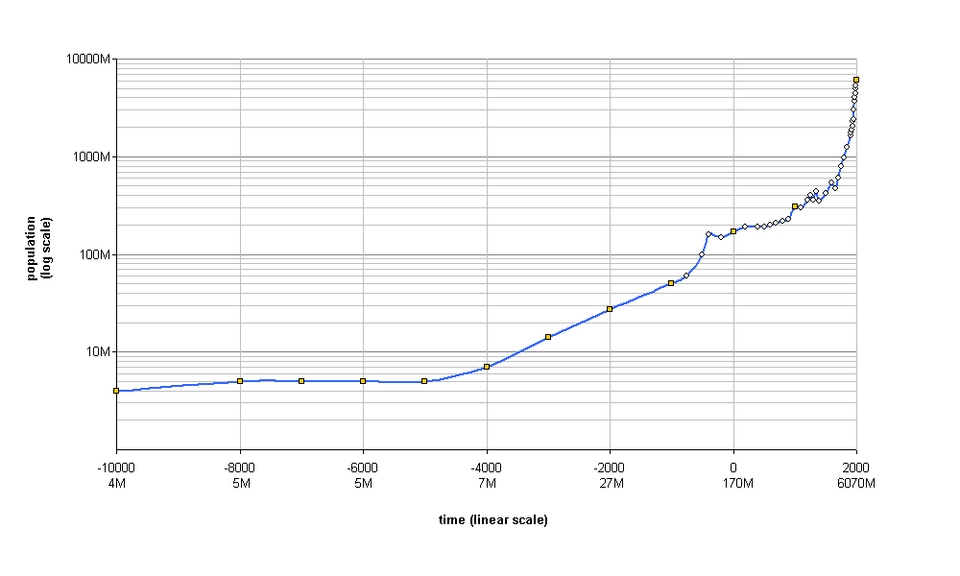

This graph displays global population growth from early human history through 2000 CE, highlighting how slowly population grew for most of history and how sharply it accelerated in the modern era. The logarithmic vertical axis makes early and recent growth visible on the same chart. The log scale is an extra detail not required by the syllabus but clarifies long-term demographic change. Source.

Before industrialization, both fertility (the number of children born per woman) and mortality (rates of death across a population) were high, resulting in slow or unstable growth.

The spread of modern agriculture, improved transportation, and better food storage gradually reduced famine-related mortality.

Major declines in death rates during the Industrial Revolution accelerated population growth as public health systems, sanitation, and medicine improved.

Fertility remained high during early industrialization, producing rapid natural increase.

Over time, fertility declined in many regions as urbanization, rising education levels, and shifting cultural expectations influenced family size.

These changes demonstrate how mortality and fertility do not always fall simultaneously, producing periods of population expansion followed by stabilization.

Contemporary Variations in Growth and Decline

Modern demographic trends show significant regional differences in population change.

Many less economically developed regions continue to experience high fertility alongside declining mortality, creating rapid population growth.

More developed regions often exhibit low fertility and low mortality, resulting in slow growth, zero growth, or natural decline.

Some countries face sub-replacement fertility, meaning the average number of births per woman falls below the replacement level necessary to maintain population size.

Improved medical care, nutrition, and technology contribute to increased life expectancy worldwide, reducing mortality even where fertility decreases.

These contemporary trends reveal global divergence: some regions grow quickly while others confront aging and shrinking populations.

Fertility Trends Over Time

Fertility has played a central role in shaping population patterns historically and today. When fertility is first introduced, it requires a definition.

Fertility: The average number of children born to women of childbearing age within a population.

Fertility trends have shifted substantially across eras and regions.

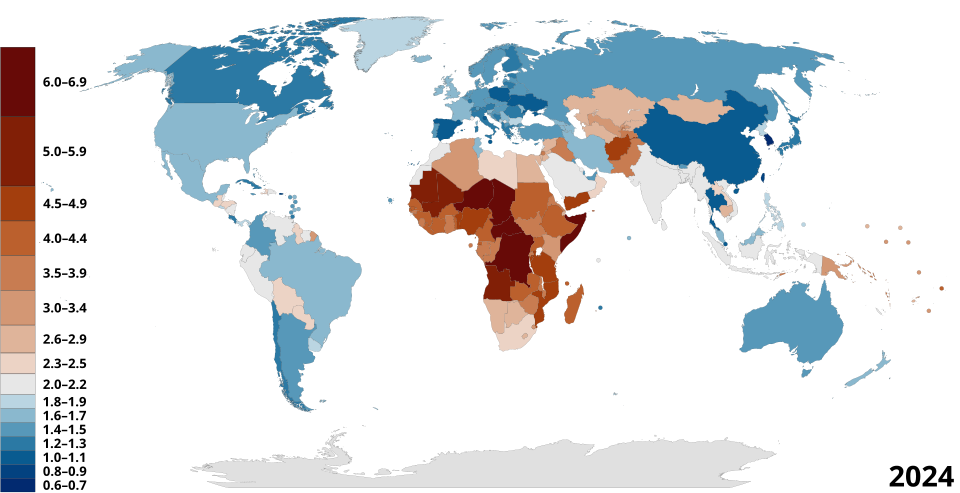

This map shows total fertility rates by country, illustrating global variation in average births per woman. Regions of high fertility contrast sharply with areas experiencing low or sub-replacement fertility. The map includes additional category ranges beyond the syllabus requirement but simply provides more detailed examples of fertility differences. Source.

Major influences include:

Urbanization, which often reduces family size because children are more costly to raise in urban environments.

Education, especially of women, which correlates strongly with delayed childbirth and fewer children.

Economic change, including movement from agricultural to industrial and service economies.

Cultural expectations, such as norms around marriage, gender roles, or ideal family size.

Government policies, including pronatalist or antinatalist initiatives, which encourage larger or smaller families.

Changing fertility levels directly influence long-term population growth trajectories by altering the number of births across generations.

Mortality Trends Over Time

Mortality decline has consistently been a major driver of population growth.

Mortality: The frequency of deaths within a population, typically measured by the crude death rate.

Advances affecting mortality over historical and contemporary periods include:

Public health improvements, such as sanitation, clean water systems, and vaccinations.

Medical innovations, including antibiotics, surgical techniques, and expanded health-care access.

Nutrition improvements, which reduce vulnerability to disease.

Reduced infant mortality, which especially impacts population trends because children represent a large share of potential future adults.

Modern mortality rates are generally lower than at any time in history, although disparities persist across regions due to socioeconomic inequality, conflict, and uneven access to health care.

Migration Trends Over Time

Migration contributes to population growth or decline depending on whether a country or region experiences net in-migration or out-migration.

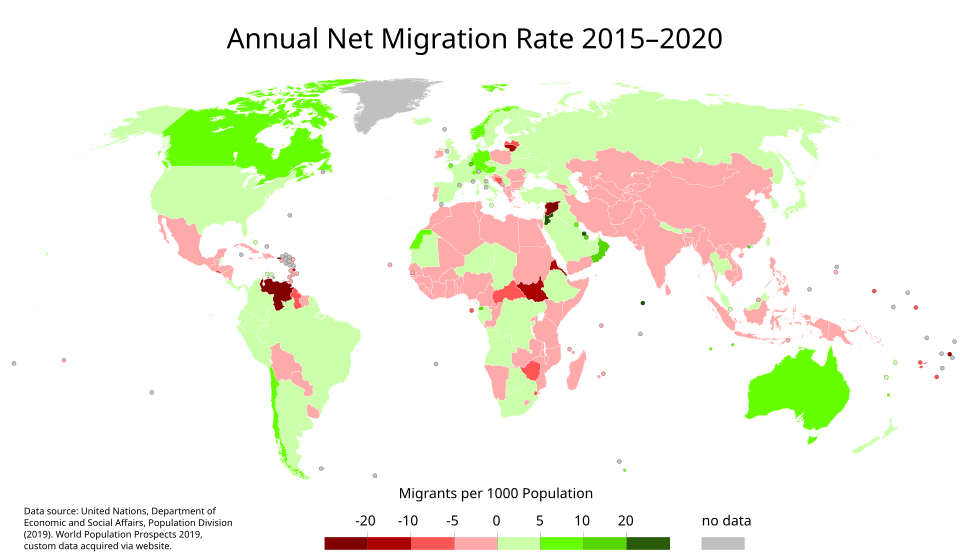

This world map illustrates net migration rates from 2015–2020, showing where more people arrive than leave and where departures exceed arrivals. It demonstrates migration’s ability to increase or decrease national populations. The specific time window is more detailed than the syllabus requires but offers a clear contemporary example of migration patterns. Source.

Unlike fertility and mortality, migration can shift rapidly in response to political or economic circumstances.

Key influences on migration trends include:

Economic opportunities that attract workers to growing regions or urban centers.

Political instability, conflict, or persecution that drives forced migration and refugee flows.

Environmental change, including droughts, sea-level rise, or natural disasters.

Policy changes, such as immigration quotas or border enforcement, which can expand or restrict movement.

Migration can offset low fertility in some countries by increasing the working-age population, while sustained out-migration can intensify population decline in others.

Linking Fertility, Mortality, and Migration to Growth and Decline

Population trends emerge from the combined effects of all three demographic components. Their interactions produce several recognizable patterns:

Rapid growth occurs when mortality declines faster than fertility and when migration adds to population size.

Slower growth or stabilization occurs when fertility declines to balance mortality, often in middle-income or transitioning economies.

Population decline arises when fertility falls below replacement, mortality remains low or stable, and migration does not compensate for fewer births.

Aging populations develop when fertility stays low and life expectancy rises, shifting the population structure toward older age groups.

These interconnected processes explain why populations change over time and why different regions experience distinct demographic trajectories within the same historical period.

FAQ

Policies in areas such as housing, childcare, education, and labour markets shape demographic behaviour by influencing the cost and practicality of raising a family or remaining in a country.

For example:

High housing costs can discourage family formation.

Limited childcare availability may reduce the number of children parents decide to have.

Restrictive employment conditions may prompt out-migration of young workers.

These indirect effects accumulate, reinforcing long-term growth or decline even in the absence of explicit population policy.

Cultural factors can reshape fertility independently of economics by altering expectations around family size, marriage age, and gender roles. Shifts in norms related to women’s autonomy, relationship timing, and personal lifestyle priorities can reduce birth rates even in societies without major economic transformation.

Cultural globalisation can also spread ideas that favour smaller families, influencing fertility over multiple generations.

Countries may experience modest growth when mortality falls but fertility is already low or declining. If the number of children born each generation decreases, reduced mortality does not translate into significant population expansion.

In addition, out-migration can offset the population gains produced by lower death rates, particularly in regions where younger adults leave in search of employment.

Migration typically involves specific age groups, especially young adults. When these groups move in or out in large numbers, the age structure shifts noticeably.

In-migration of young workers lowers the median age.

Out-migration of young adults accelerates population ageing.

Migration of dependent groups (such as older retirees) creates different pressures on services and labour markets.

These shifts accumulate over time, producing long-term demographic impacts.

Sustained sub-replacement fertility leads to shrinking cohorts of children, which gradually reduces the working-age population as smaller generations move through the age structure.

Over time, this creates:

A rising dependency ratio

Increasing pressure on pension and health-care systems

Potential labour shortages that can alter immigration policies

Urban contraction in regions unable to attract migrants or retain younger workers

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way declining mortality rates have contributed to population growth over time.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that declining mortality reduces the number of deaths in a population.

1 mark for explaining that more people surviving into adulthood increases overall population size.

1 mark for linking this trend to historical developments such as improvements in sanitation, medicine, or public health that lowered death rates.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how changes in fertility, mortality, and migration together shape long-term trends in population growth and decline.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing how falling fertility affects long-term population change (e.g., slowing growth or leading to decline).

1 mark for describing how falling mortality contributes to growth by increasing life expectancy and reducing early death.

1 mark for explaining how migration can offset low fertility or accelerate decline depending on net in- or out-migration.

1 mark for providing at least one example that accurately links a demographic trend to a specific region or country.

1 mark for analysing the interaction between two demographic components (e.g., low fertility combined with low mortality leading to ageing).

1 mark for a coherent explanation showing how all three components collectively influence long-term demographic trends.