AP Syllabus focus:

‘Demographic change is driven by three factors: fertility, mortality, and migration.’

Population change results from measurable demographic processes that alter the size and structure of populations over time, shaping regional patterns and influencing broader geographic trends.

Components of Population Change

Population geographers analyze three essential demographic forces that determine whether a population grows, declines, or remains stable over time. These components—fertility, mortality, and migration—operate across diverse spatial scales and vary with social, economic, political, and environmental conditions.

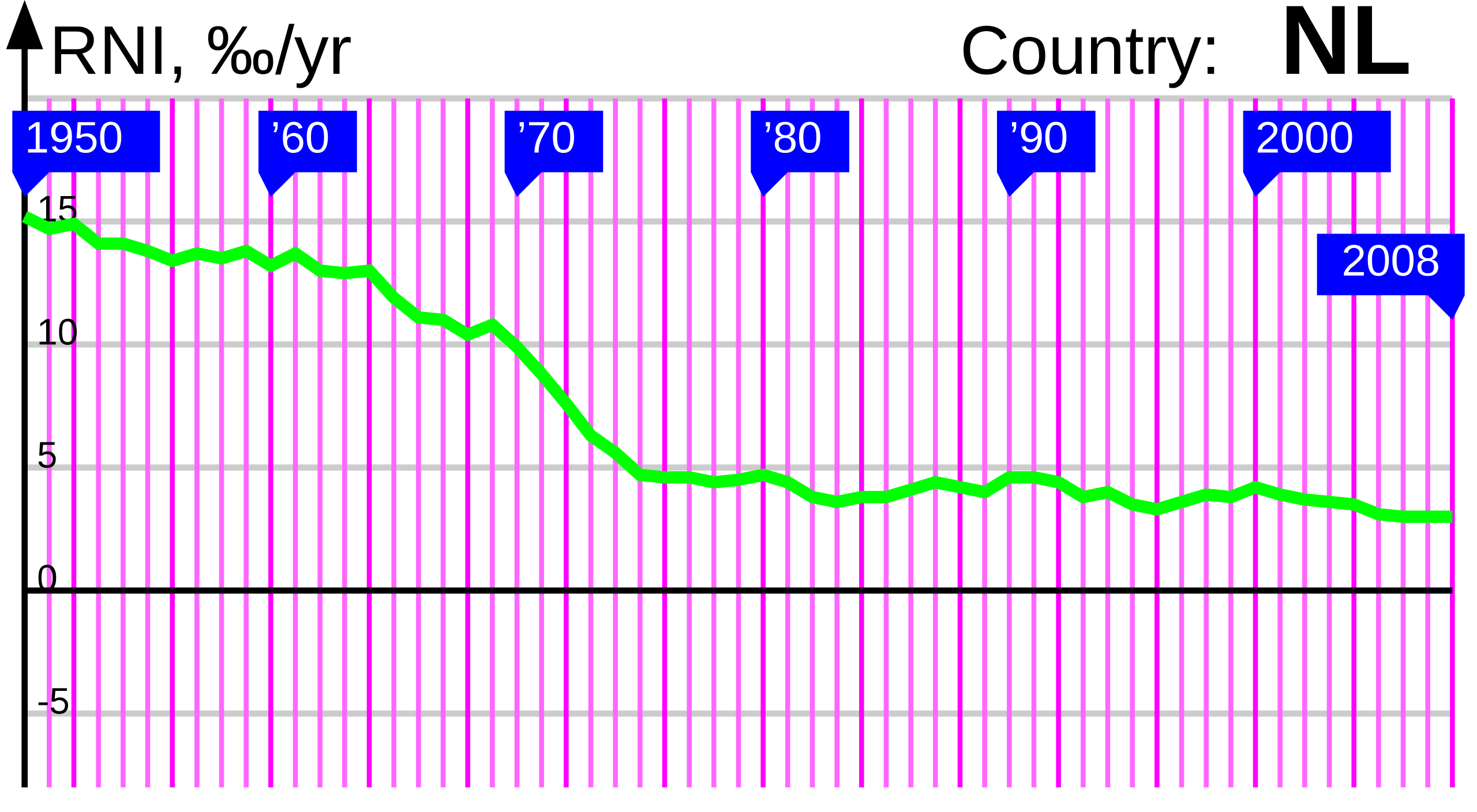

This line graph shows the rate of natural increase in the Netherlands from 1950 to 2008, demonstrating how the difference between birth and death rates declines over time in a high-income country. It visually reinforces the idea that natural increase can approach very low or negative values. The example is specific to one country but clearly illustrates patterns discussed in this subtopic. Source.

Fertility

Fertility refers to the frequency of childbearing within a population and directly contributes to natural population increase.

Fertility: The demographic process involving the number of live births occurring in a population.

Fertility levels differ substantially across regions due to cultural expectations, access to health services, economic opportunities, government policies, and the social roles of women. Geographers often rely on specialized measures to understand fertility patterns. One key measure is the crude birth rate (CBR), introduced here because it is central to analyzing fertility’s influence on population change.

Crude Birth Rate (CBR): The number of live births per 1,000 people in a population per year.

Fertility affects age structure, dependency ratios, and long-term population momentum. Regions with persistently high fertility tend to experience youthful populations, rapid natural increase, and heightened demand for services such as education and maternal health care. In contrast, regions with low fertility frequently face slowing growth and emerging challenges tied to population aging.

Mortality

Mortality refers to the incidence of death within a population, shaping the pace at which population size changes through natural decrease or slower natural increase.

Mortality: The demographic process involving the number of deaths occurring within a population.

Geographers employ the crude death rate (CDR) to evaluate mortality at different scales.

Crude Death Rate (CDR): The number of deaths per 1,000 people in a population per year.

Mortality varies with access to nutrition, medical care, sanitation, political stability, environmental risks, and socioeconomic inequality. Declining mortality, especially due to improved health care and reduced prevalence of infectious diseases, has historically been one of the most significant drivers of population growth. Shifts in mortality strongly influence life expectancy, which reflects broader living conditions and quality of life.

Natural Increase

The relationship between fertility and mortality determines natural increase, which measures population change excluding migration. Natural increase grows when births outnumber deaths and declines when the opposite occurs. This indicator helps geographers assess whether internal demographic processes alone can sustain population growth.

= Crude Birth Rate (births per 1,000 people per year)

= Crude Death Rate (deaths per 1,000 people per year)

Natural increase varies worldwide, with high-income regions often showing low or negative RNIs, while many low- and middle-income regions experience higher natural increase rates due to younger age structures and higher fertility.

Migration

Migration is the permanent or semi-permanent movement of people from one location to another. Unlike fertility and mortality, which produce natural increase or decrease, migration produces net migration, which adds to or subtracts from population totals depending on whether more people enter or leave a place.

Migration: The movement of people across significant distances that results in a change of residence.

Migration is influenced by economic opportunities, environmental conditions, political conflict, cultural ties, demographic pressures, and global interconnections. Geographers distinguish between immigration (movement into a place) and emigration (movement out of a place). When immigration exceeds emigration, a region experiences positive net migration; when emigration exceeds immigration, net migration is negative.

Migration uniquely affects population composition. Because migrants are often working-age adults, migration can reshape labor forces, alter dependency ratios, and change the cultural and social landscapes of both sending and receiving regions. It may also modify population growth, either accelerating it where immigration is high or contributing to decline where emigration predominates.

Combined Effects on Population Change

The interplay of fertility, mortality, and migration produces distinct population trajectories across the world. Geographers examine these components together because they rarely operate independently. For example, high fertility may coincide with declining mortality, amplifying natural increase, while strong out-migration may offset growth from high birth rates.

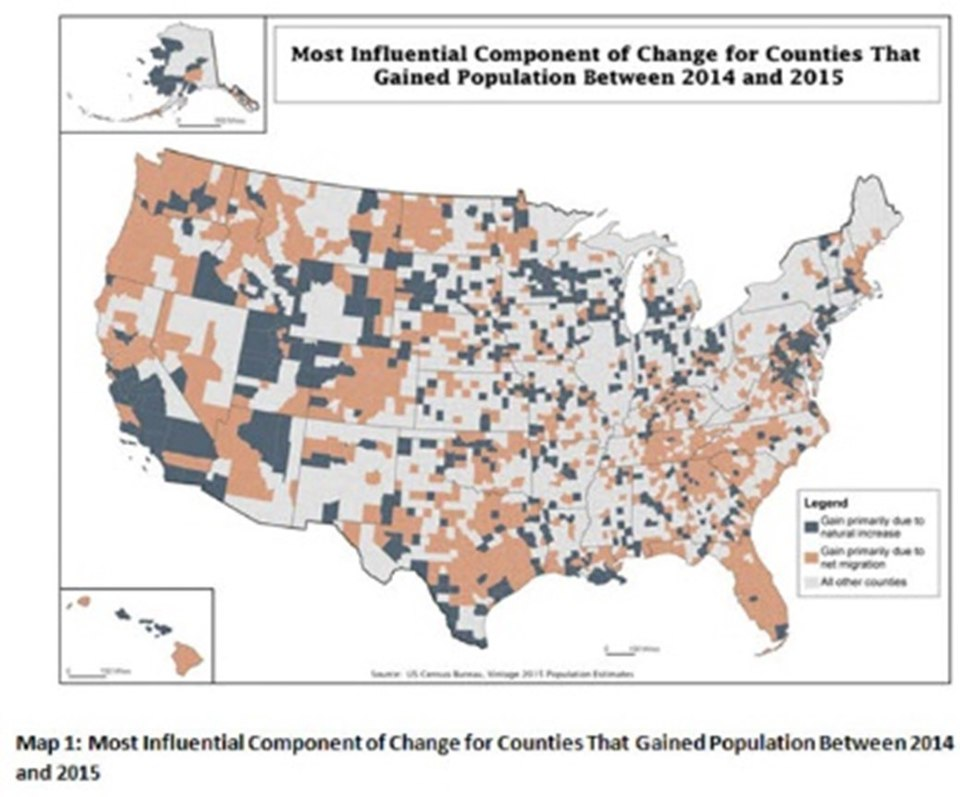

This map illustrates whether population growth in U.S. counties between 2014 and 2015 was driven more by natural increase or by net migration. It demonstrates how births, deaths, and migration combine differently across regions to produce overall population change. Although focused on one country, it effectively reinforces the demographic processes described in this subtopic. Source.

Key interactions shaping population outcomes include:

High fertility + declining mortality: Rapid natural increase and youthful age structures.

Low fertility + low mortality + positive net migration: Slow but stable growth.

Low fertility + rising mortality + negative net migration: Population decline or aging.

High fertility + high out-migration: Moderated growth or even stagnation.

These components form the foundation of demographic analysis, enabling geographers to interpret past trends and anticipate future population patterns.

FAQ

Age structure affects fertility, mortality, and migration because different age groups contribute differently to each process.

• A youthful population typically has higher fertility because a larger share of people are in reproductive ages.

• Mortality patterns shift as populations age, with older populations experiencing higher death rates.

• Migration is often dominated by working-age adults, which can temporarily reshape age structure and, in turn, influence future fertility and mortality trends.

Standardised measures such as crude birth and death rates allow geographers to make meaningful comparisons across places with different population sizes.

This helps reveal whether differences in population change stem from underlying social, economic, or political conditions rather than simple variation in population scale.

Using consistent measures also helps identify global patterns, regional outliers, and long-term demographic transitions.

Policies not explicitly about population can still shape demographic patterns.

• Investments in healthcare reduce mortality and may influence fertility decisions.

• Education reforms, especially for girls and women, tend to lower fertility rates.

• Economic policies that affect job availability can drive migration flows.

These indirect effects are significant because they demonstrate how population change is tied to broader governance.

Migration can rapidly alter population size because movement happens over short time frames, whereas births and deaths change population numbers more gradually.

Migrants are often concentrated in specific age groups, giving migration an outsized influence on labour force size, dependency ratios, and population structure.

This immediacy makes migration a key factor in short-term demographic change.

Environmental factors can shape fertility, mortality, and migration in different ways.

• Environmental hazards such as droughts and floods may increase mortality or drive migration.

• Areas with stable climates and reliable resources may support higher fertility by reducing uncertainty.

• Long-term environmental degradation can trigger sustained out-migration, altering regional population dynamics.

These links highlight the importance of considering environmental context in demographic analysis.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one component of population change that contributes to natural increase.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for correctly identifying either fertility or mortality.

• 1–2 marks for explaining how the chosen component contributes to natural increase (for example, higher fertility increases natural increase; higher mortality decreases natural increase).

• Maximum 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how migration can influence population change in a region, and explain why its effects may differ from those of fertility and mortality.

Mark scheme:

• 1–2 marks for describing migration as movement of people into or out of a region (immigration/emigration).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how migration alters population size through net migration (positive or negative).

• 1–2 marks for analysing why migration’s effects differ from natural increase processes (for example, migration often involves working-age adults, may rapidly alter population structure, can offset low fertility or high mortality).

• Maximum 6 marks.