AP Syllabus focus:

‘Changing social, economic, and political roles for women influence patterns of fertility and mortality in different parts of the world.’

Changing roles of women reshape demographic patterns worldwide, as shifts in education, employment, rights, and autonomy alter decisions about childbearing and influence health, longevity, and mortality trends.

Changing Roles of Women and Demographic Outcomes

The relationship between women’s roles and demographic change is central to understanding global variations in fertility and mortality. As women gain wider access to education, employment opportunities, and political voice, family formation patterns and health outcomes shift significantly. These transformations influence how quickly populations grow, age, or stabilize.

Expanding Educational Opportunities

Education is one of the strongest predictors of demographic change. When women access higher levels of schooling, they typically experience rising autonomy and delayed life transitions.

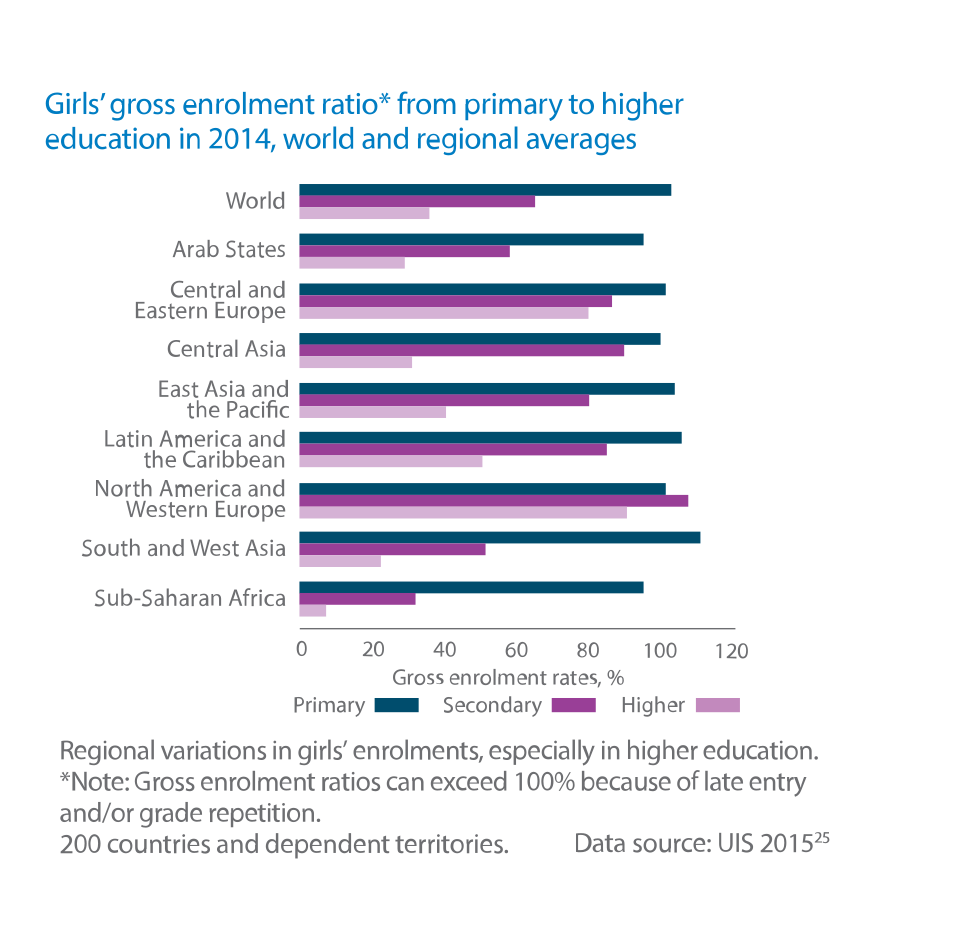

Girls’ enrollment ratios by education level show how access to schooling varies across regions. Higher secondary and tertiary enrollment correlate with delayed marriage and reduced fertility. The detailed breakdown exceeds syllabus depth but strongly reinforces the demographic importance of women’s expanding education. Source.

How Education Influences Fertility

Increased school enrollment encourages women to delay marriage and postpone childbearing, reducing total fertility levels.

Schooling provides knowledge about health, reproductive rights, and contraception, enabling informed decisions about family size.

More-educated women often prioritize career development alongside family goals, leading to smaller desired families.

Autonomy: The ability of individuals to make independent decisions regarding their lives, including family formation, employment, and health.

These educational effects contribute to substantial declines in fertility rates across many middle-income countries, especially where gender equity policies support women’s continued schooling.

Women in the Labor Force

As women enter and remain in the workforce, household economic structures and demographic patterns evolve.

Economic Participation and Demographic Shifts

Higher labor-force participation lowers fertility by increasing the opportunity cost of early or frequent childbearing.

Dual-income households often invest more heavily in each child, which can favor having fewer children overall.

Urban labor markets create lifestyles that value mobility and delay parenthood.

Opportunity Cost: The benefits or income given up when choosing one option over another, such as leaving work to have or care for children.

Countries with strong protections—maternity leave, childcare access, and workplace equality—tend to experience moderated fertility decline, as women can balance career and family more easily.

Changing Social Norms and Gender Expectations

Shifting cultural values play a major role in demographic transitions. Traditions that once prioritized early marriage or large families increasingly give way to norms supporting gender equality.

Social Transformations Affecting Fertility

Delayed marriage and greater acceptance of nontraditional family structures reduce early births.

Growing social support for women’s independence leads to more decision-making power in reproductive choices.

In many societies, declining emphasis on patriarchal norms correlates with reduced fertility and greater spacing between births.

These cultural changes help explain why fertility decline is rapid in some regions even before major economic development occurs.

Political Empowerment and Demographic Decisions

Women’s participation in governance and policymaking influences demographic outcomes both directly and indirectly.

Political Factors

When women hold political office, governments are more likely to invest in public health, education, and family planning, improving maternal health and reducing mortality.

Gender-equal legal structures—property rights, inheritance laws, and protections against discrimination—create more stability for women, influencing decisions about marriage and childbirth.

Policies supporting reproductive rights expand access to contraception and safe medical care, lowering fertility and maternal mortality simultaneously.

Maternal Mortality: The death of a woman from pregnancy-related causes during pregnancy, childbirth, or shortly afterward.

A single sentence here ensures appropriate separation before the next thematic discussion.

Health Care Access and Its Mortality Implications

Women’s changing roles often coincide with expanded access to health services, which significantly shapes mortality patterns.

Improved Health Outcomes

Access to prenatal and postnatal care decreases risks during pregnancy and childbirth.

As women become health decision-makers for households, child mortality also declines.

Expanding access to modern healthcare, nutrition, and preventive services increases life expectancy for women and their families.

In many rapidly developing countries, falling mortality precedes or accelerates fertility decline, creating new demographic structures and age compositions.

Regional Differences in Demographic Effects

Although global trends are broadly similar, demographic outcomes vary across regions due to differences in economic development, political systems, cultural norms, and gender policies.

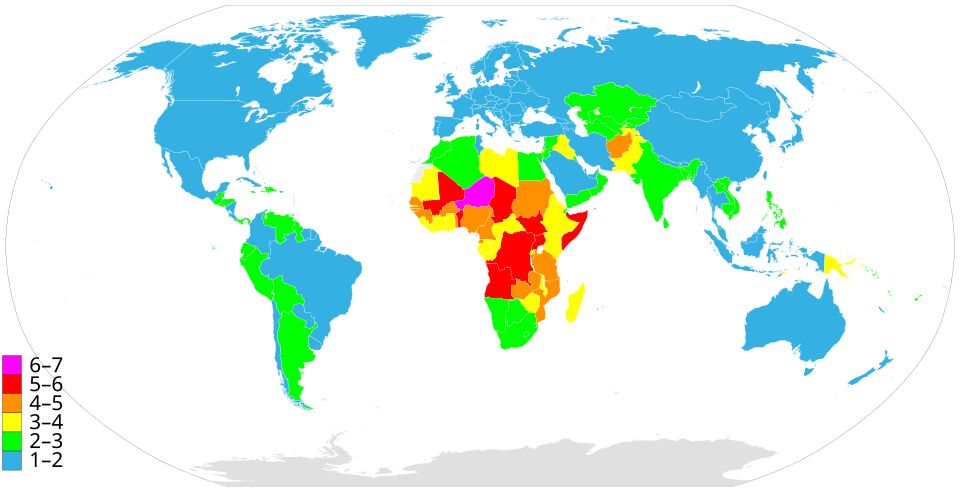

This world map displays total fertility rates by country, revealing where fertility remains high and where it has fallen to low levels. These spatial differences reflect regional contrasts in women’s education, employment, gender norms, and policy environments. The map focuses solely on fertility, so students should interpret it alongside the text on women’s changing roles. Source.

Variation Across the World

In high-income regions, women’s equality and economic participation often correlate with very low fertility, sometimes below replacement level.

In middle-income regions, rapid improvements in education and employment create swift declines in fertility and mortality, accelerating demographic transition.

In lower-income regions with limited gender equality, fertility remains high and maternal mortality is elevated, though gradual shifts in schooling and employment are beginning to transform these trends.

Understanding these regional distinctions helps geographers explain why demographic transitions unfold at different rates and in different ways worldwide.

Interconnected Outcomes

Women’s shifting roles across social, economic, and political spheres create compound effects that reshape demographic landscapes. These changes influence fertility decisions, health outcomes, and long-term population structures, making the study of gender central to population geography.

FAQ

Countries where women gain access to education, employment, and legal rights earlier tend to enter later stages of the demographic transition more quickly.

This happens because fertility declines faster when women delay marriage, have greater autonomy in family planning, and participate more fully in formal employment.

In contrast, regions where gender norms change slowly may experience prolonged high fertility and slower improvements in mortality.

Women in political positions tend to prioritise policies linked to family welfare, such as vaccination programmes, nutrition support, clean water systems, and maternity services.

These investments improve not only maternal health but also infant and child survival, leading to lower mortality at multiple life stages.

Urban environments generally provide better access to education, healthcare, and formal employment for women, all of which support greater reproductive autonomy.

Urban living also increases the cost of raising children—housing, childcare, transport—which encourages smaller families.

Daily routines in urban areas often favour career development and later family formation, contributing to lower fertility.

Cultural changes often include:

• Reduced pressure for early marriage

• Increased acceptance of women’s career aspirations

• Shifts from extended-family to nuclear-family expectations

• Greater acceptance of diverse family forms

These cultural adjustments reshape expectations around childbearing and reduce social pressure to have larger families.

Regions offering strong economic opportunities for women—such as access to formal employment, equal pay, and workplace protections—tend to experience slower population growth due to reduced fertility.

Areas with restricted economic participation for women see higher fertility, reinforcing faster population growth and often deeper economic dependency.

Over time, these differences contribute to widening demographic and economic disparities between regions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which increased participation of women in the labour force can influence a country’s fertility rate.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a valid influence (for example, delayed childbirth).

• 1 mark for explaining the mechanism (for example, employment increases the opportunity cost of having children).

• 1 mark for linking this to the overall effect on fertility (for example, women choose to have fewer children).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how changing social, economic, and political roles of women can lead to variations in fertility and mortality rates between regions.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a social factor (for example, changing gender norms or delayed marriage).

• 1 mark for explaining how this affects fertility or mortality.

• 1 mark for identifying an economic factor (for example, higher female labour force participation).

• 1 mark for explaining its demographic effect (for example, reduced fertility due to increased work commitments).

• 1 mark for identifying a political factor (for example, representation or supportive policies).

• 1 mark for linking political changes to demographic outcomes (for example, improved maternal health reducing mortality).