AP Syllabus focus:

‘Changing social values and access to education, employment, health care, and contraception have reduced fertility rates in many regions.’

Education, Health, and Fertility Decline

A more educated and healthier population tends to have fewer children as social values shift, opportunities expand, and families adjust reproductive decisions in response to changing conditions.

Understanding the Link Between Social Change and Fertility

The decline in fertility—the average number of children born per woman—is closely tied to improvements in education, health, women’s rights, and access to contraception. As societies develop socially and economically, households reassess family size, and women gain greater autonomy over reproductive choices. These interrelated forces shape demographic behavior across world regions and form a central concept in AP Human Geography.

Education as a Driver of Fertility Decline

Education influences nearly every dimension of demographic change. When women receive more years of schooling, they gain knowledge, opportunities, and decision-making power that reshape reproductive outcomes.

Expanding Schooling Opportunities

Access to formal education increases literacy, employment options, and awareness of family-planning tools.

In this classroom in South Sudan, girls engage in formal schooling as part of a girls’ education project. The image highlights how expanding access to education for girls in lower-income regions can alter life chances and future family-size decisions. The photograph focuses on education and does not directly depict fertility or contraception, but it provides a concrete visual example of one key driver of fertility decline discussed in the notes. Source.

Educated women often delay marriage, enter the workforce, and develop different expectations for family life.

Fertility Rate: The average number of children a woman is expected to have during her lifetime.

After education expands, fertility commonly declines because women experience additional pathways for social and economic fulfillment beyond childbearing.

Key mechanisms linking education and fertility decline include:

Delayed marriage and childbirth, as schooling continues into later adolescence and early adulthood.

Higher labor force participation, increasing opportunity costs of having large families.

Greater knowledge of reproductive health, including how to plan and space pregnancies.

Shifts in gender norms, as education promotes expectations of equality and autonomy.

Health Conditions and Demographic Outcomes

Health improvements also contribute directly to fertility decline. In many developing regions, fertility has historically been high because child mortality was high. As health care expands and survival improves, families choose to have fewer children.

Improvements in Infant and Child Health

Access to vaccination, prenatal care, and basic medical services reduces deaths among infants and young children. When parents are confident their children will survive into adulthood, they no longer feel pressure to have many children to ensure family continuity.

Child Mortality Rate: The number of deaths of children under age five per 1,000 live births.

Enhanced health systems therefore shape fertility preferences by reducing uncertainty about child survival. This process is strongly associated with economic development and state investment in health infrastructure.

The Role of Contraception and Reproductive Health Access

Reliable contraception is a critical factor enabling individuals to control the number and timing of births. As contraceptive access expands, fertility falls because people are able to align reproductive behavior with personal goals.

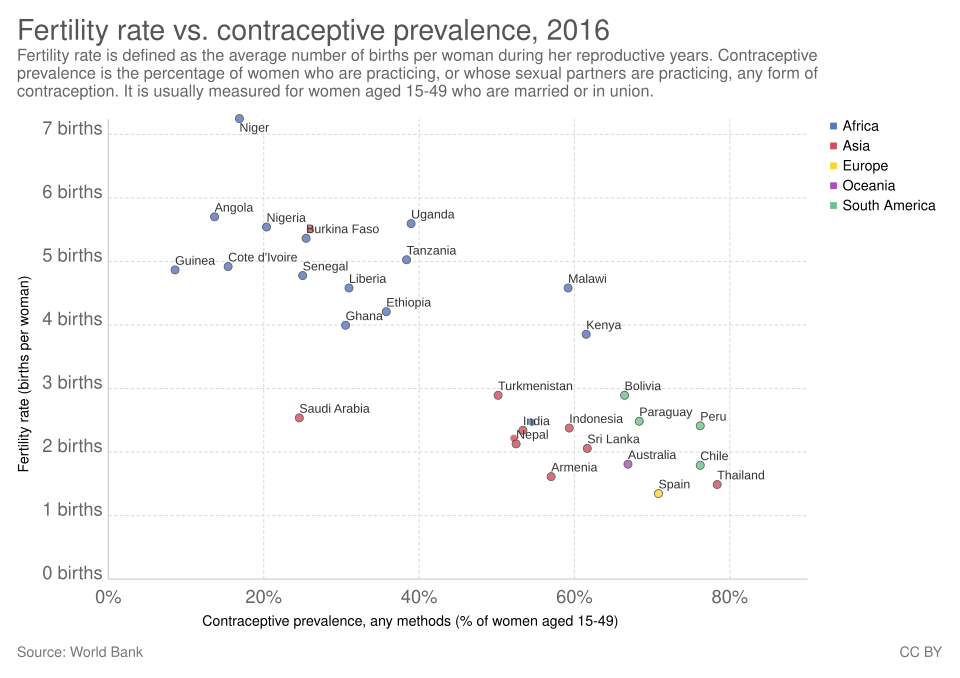

This scatterplot compares the average number of children per woman to the share of women using contraception in different countries. Most points slope downward, showing that higher contraceptive prevalence is strongly associated with lower fertility. The chart includes specific country markers and exact percentages that go beyond the syllabus, but all added detail reinforces the core relationship between contraception and fertility decline. Source.

Modern Family-Planning Resources

Family-planning programs increase the availability of methods such as oral contraceptives, condoms, injectable hormones, and long-acting reversible devices. These allow families to space pregnancies, reduce unintended births, and pursue education or employment with fewer interruptions.

Key outcomes of increased contraceptive availability include:

Greater reproductive autonomy, especially for women.

Lower rates of unintended pregnancy.

More predictable household planning, improving economic and social stability.

A shift toward smaller, planned families, reflecting changing social expectations.

Social Values and Fertility Preferences

Beyond measurable indicators like education and health access, shifts in social values also reduce fertility. Cultural change can be gradual, but its effects on family size are powerful.

Evolving Gender Norms

As gender roles shift, societies increasingly view women as full participants in economic and political life. These changing expectations influence decisions about childbearing.

Important social factors shaping fertility preferences include:

Norms surrounding marriage, with later marriages and fewer arranged unions.

Changing attitudes about ideal family size, influenced by media, urbanization, and global cultural flows.

Rising aspirations, as families prioritize high-quality education for fewer children.

Household economic strategies, emphasizing investment in human capital rather than large family labor forces.

Employment and Fertility Decisions

Women’s participation in the workforce often leads to declines in fertility because employment creates new economic roles and raises the cost of taking time away from work to raise children.

Expanding Work Opportunities

As women enter jobs outside the home, they gain income and financial independence. This broader range of life choices can lead to delayed childbirth or decisions to have fewer children.

Employment contributes to fertility decline through:

Increased opportunity costs, where career progress may slow during periods of childrearing.

Higher household income, reducing reliance on children for economic support.

Greater autonomy, as women negotiate family size jointly rather than having decisions determined by traditional norms.

Regional Variation in Fertility Decline

While the general pattern of declining fertility occurs worldwide, the pace and intensity vary by region.

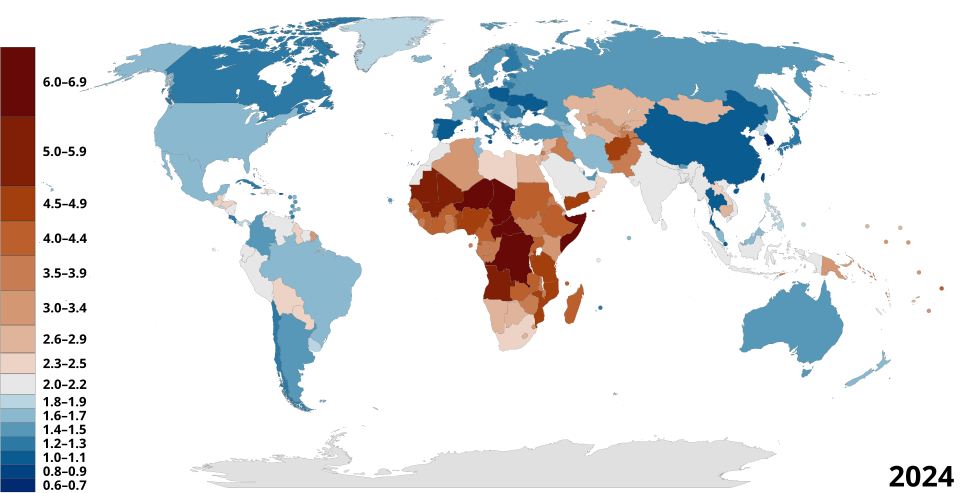

This choropleth map shows total fertility rates by country, with darker shades representing higher average numbers of children per woman. It helps illustrate that many regions in sub-Saharan Africa still have high fertility, while much of Europe, East Asia, and North America have low fertility. The image includes country-level detail beyond the syllabus, but all information supports understanding regional contrasts in fertility decline. Source.

Understanding these geographic differences helps explain why fertility decline is not uniform and highlights the importance of local context in demographic processes.

FAQ

Cultural expectations determine how much influence education has on women’s life choices. In societies where early marriage is strongly valued, even educated women may face pressure to begin childbearing soon after marriage.

Where cultural norms support women’s autonomy, the effect of education on fertility is stronger, as women can apply their skills to employment and delay childbirth without social penalty.

When child mortality is high, parents often plan for more children to ensure that some survive into adulthood. As health systems improve, these survival uncertainties decline.

Parents then shift towards having fewer children because they can expect each child to reach adulthood, reducing the need for large families as a form of social or economic security.

Urban areas typically provide better access to clinics, pharmacies, and trained health professionals, making contraception more accessible and reliable.

In addition, urban living raises the cost of raising children due to housing, childcare, and schooling expenses, encouraging smaller family sizes and greater use of family-planning services.

When women hold stable jobs, the opportunity cost of having many children increases. Employment encourages strategic planning of births to avoid long interruptions from the labour market.

Contraception supports this planning by enabling women to delay or space pregnancies while maintaining participation in paid work, reinforcing long-term trends toward smaller families.

Fertility decline depends on more than health care alone. Regions may experience slower change due to limited contraceptive access, strong pronatalist cultural norms, or low female education levels.

Political instability, rural isolation, and weak infrastructure can also hinder the spread of reproductive health services, reducing the pace of demographic transition despite better health conditions.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which increased access to education can lead to a decline in fertility rates.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid link between education and fertility decline (e.g., delayed marriage or childbearing).

1 mark for explaining the mechanism (e.g., increased knowledge of family planning, greater career aspirations).

1 mark for providing a clear demographic consequence (e.g., fewer children per woman, reduced overall fertility rate).

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how improvements in women’s health care and access to contraception contribute to long-term reductions in fertility in different world regions.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1 mark for identifying at least one health-related factor reducing fertility (e.g., improved child survival, maternal health services).

1 mark for identifying at least one contraception-related factor (e.g., availability of modern contraceptive methods).

1–2 marks for explaining how each factor influences fertility behaviour (e.g., reduced need for large families when child mortality falls).

1–2 marks for using examples or regional contrasts (e.g., fertility decline in South Asia linked to expanded reproductive health services; sub-Saharan Africa showing slower change).

Answers that demonstrate well-developed analysis with accurate geographical understanding should receive the highest marks.