AP Syllabus focus:

‘Changes in women’s roles also influence migration patterns, as illustrated by Ravenstein’s laws of migration.’

Women’s shifting social, economic, and political roles reshape migration patterns worldwide, influencing who moves, why they move, and how these patterns align with Ravenstein’s laws of migration.

Women’s Evolving Roles and Their Migration Impacts

Changing roles for women—especially increased access to education, employment, and political participation—affect both the likelihood of migration and the types of migration women undertake. As women gain greater autonomy, they increasingly make independent mobility decisions rather than migrating only as dependents within households. These dynamics reshape long-standing gendered migration trends historically observed by geographers.

Shifts in Women’s Education and Employment

Expanding educational attainment gives women the skills and qualifications needed to participate in diverse labor markets. Greater access to paid employment strengthens financial independence, making voluntary migration more feasible. Women may now migrate for:

Professional and career opportunities

Domestic and care-work jobs in global labor markets

Access to higher education

Escape from gender-based discrimination or restricted social roles

Increasing participation in skilled and unskilled labor markets creates distinct spatial patterns, including flows from low-income to high-income regions where demand for female labor has grown.

Changes in Social and Cultural Expectations

As gender norms shift, families and societies increasingly support women’s mobility. Changing expectations can reduce constraints on movement, allowing women to migrate at younger ages, over longer distances, and for a wider range of reasons. These trends also reflect broader transformations in family life, fertility patterns, and household structures.

Ravenstein’s Laws of Migration and Gendered Patterns

Ravenstein’s foundational ideas, developed in the late 19th century, continue to guide geographic analysis of migration flows. Although the laws were based on male-dominated patterns of the industrial era, they help explain how women’s changing roles modify traditional trends.

Key Elements of Ravenstein’s Laws Relevant to Women’s Migration

Many of Ravenstein’s laws intersect with gender, particularly those concerning distance, motives, and demographic characteristics of migrants.

Short-distance movement dominates: Women historically moved shorter distances, often for marriage or family reasons. Increasing female participation in the workforce has expanded women’s long-distance voluntary migration.

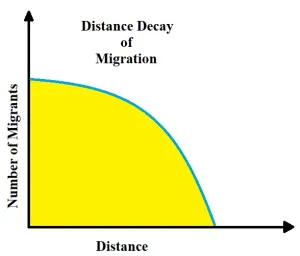

This diagram shows the principle that the number of migrants declines as distance increases, illustrating Ravenstein’s distance-decay concept. It visually reinforces why short-distance moves historically dominated migration patterns. The diagram includes only the distance–migration relationship and no additional concepts beyond the syllabus requirement. Source.

Economic motives drive most migration: Ravenstein identified economic opportunity as a primary motivator. This remains true, but growing female economic agency broadens the gender composition of labor migration streams.

Long-distance migrants are more likely to be adults seeking employment: Women now constitute a rising share of such migrants, especially in global care economies centered in cities and wealthy nations.

Urban areas attract more migrants: Women migrate to cities for education, employment in manufacturing and services, and improved social freedoms, reinforcing urbanization processes.

As women’s autonomy increases, the traditional gender divisions Ravenstein observed—men traveling long distances for work and women staying closer to home—continue to weaken.

Defining Chain Migration and Its Gender Dimensions

Chain migration plays a significant role in women’s mobility. It occurs when migrants follow family or community members to a destination previously established by earlier migrants.

Chain Migration: The process by which migrants move to places where networks of family, friends, or community members have already settled.

Women have long participated in chain migration, but their increasing agency means they may initiate—rather than simply follow—migration chains. Female-led chains can reshape household migration strategies, encouraging additional family members to join later.

Women’s participation in chain migration often depends on social networks that facilitate finding employment, housing, and childcare, making it especially important for female migrants navigating unfamiliar places.

A sentence placed here ensures proper spacing before the next definition block.

Step Migration: A form of migration in which movement occurs in stages, such as from a rural area to a town, then to a city, and possibly onward to a more distant urban center.

Women’s step migration frequently reflects layered decision-making shaped by safety concerns, access to jobs, and cultural expectations. For example, women may migrate first to a nearby small city where networks exist before moving to larger metropolitan regions with broader opportunities.

Female Migration and Intervening Obstacles

While women migrate for many of the same reasons as men, they often encounter distinct intervening obstacles, including gender-based violence, legal restrictions, household responsibilities, and cultural limitations on female mobility. These obstacles influence route choice, timing, and destination.

Women may also benefit from intervening opportunities, such as:

Availability of domestic or service-sector jobs

Safe housing networks organized by migrant communities

NGOs providing legal and social support for female migrants

Educational access not available in their origin regions

These opportunities intersect with Ravenstein’s emphasis on economic motivations and urban attractions, further reinforcing gendered migration patterns.

Women, Forced Migration, and Ravenstein’s Insights

Although Ravenstein focused primarily on voluntary migration, analyzing women’s mobility also requires acknowledging forced migration, including displacement caused by conflict, persecution, environmental stress, and gender-based violence. Women often migrate under threats unique to their gender, shaping global refugee flows and altering demographic compositions of origin and destination regions.

Spatial Patterns Resulting from Women’s Migration

Contemporary migration shows several spatial patterns tied to women’s changing roles:

Increased female participation in global labor migrations, especially in domestic, health care, and manufacturing sectors

Today, many women migrants from low- and middle-income countries work in agriculture, domestic service, manufacturing, and care work, often moving as part of regional migration systems.

This image shows a Cambodian woman migrant worker celebrating a successful rice harvest. It illustrates how women’s migration is closely tied to rural livelihoods, agricultural labor, and remittances. The broader participatory-photography context is not required by the AP syllabus but helps highlight women migrants’ lived experiences. Source.

Growth of female-headed migration chains supporting newcomers

Rising representation of women in rural-to-urban migration, especially in rapidly industrializing countries

Greater engagement in international education migration, expanding long-distance flows

These patterns illustrate how transitions in women’s societal positions reshape the geography of migration, altering trends that Ravenstein first observed and providing modern examples of his enduring migration principles.

FAQ

Gender norms influence whether women are permitted, encouraged, or discouraged from travelling alone. In societies with strict expectations around female mobility, women may require family approval or accompaniment, reducing independent migration.

In contexts with more flexible norms, women have greater autonomy to pursue education, employment, or safety elsewhere. This increases both the frequency and distance of female-led migration.

Women often rely more heavily on trusted networks for safety, accommodation, and job access, especially in unfamiliar destinations.

These networks reduce risks associated with gender-based violence or exploitation.

They also provide child care support, cultural familiarity, and socially acceptable pathways into employment sectors dominated by migrant women.

Global care chains emerge when women migrate to perform care work abroad, creating a sequence of caregiving responsibilities stretching across multiple households and countries.

This process is heavily gendered because women make up the majority of workers in domestic service, nannying, and elder care.

It links migration to both labour demand in wealthy destinations and the redistribution of caregiving duties within migrant-sending households.

Urban areas often offer women safer employment, more diverse job opportunities, and greater social freedoms than rural settings.

Women may migrate to cities to escape restrictive gender norms or forced early marriage.

Urban centres also provide access to education, health care, and support organisations that make settlement more sustainable.

Women frequently choose routes with better lighting, public transport, and community support, even if longer or more expensive.

Key concerns include:

Risk of trafficking or gender-based violence

Availability of shelters and legal assistance

Presence of diaspora groups offering safe accommodation

Reliability of border enforcement practices

These factors can significantly modify both the path and end point of women’s migration journeys.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how changes in women’s social roles can influence patterns of voluntary migration.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Identifies a relevant change in women’s social roles (e.g., increased autonomy, education, employment opportunities).

1 mark: States how this change affects migration (e.g., increased likelihood of independent migration).

1 mark: Provides a clear link to voluntary migration patterns (e.g., women moving for work or study rather than family dependence).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using Ravenstein’s laws of migration, analyse how women’s migration patterns have shifted over time. Refer to both traditional and contemporary trends in your response.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Identifies at least one of Ravenstein’s laws relevant to gender (e.g., most migrants move short distances; long-distance migrants are typically adults seeking employment).

1 mark: Describes traditional gendered migration patterns (e.g., women moving shorter distances, often for family or marriage).

1 mark: Explains contemporary changes in women’s roles (e.g., increased labour force participation, educational opportunities).

1 mark: Links these changes to shifts in migration patterns (e.g., more women in long-distance or international labour migration).

Up to 2 additional marks (max 6): Provides detailed analysis comparing historical and contemporary patterns, or gives relevant examples illustrating how women’s migration increasingly aligns with or diverges from Ravenstein’s laws.