AP Syllabus focus:

‘A cultural landscape combines physical features with human cultural expressions visible on the land.’

A cultural landscape reflects how human societies shape and interpret the environment, revealing visible evidence of cultural beliefs, economic activities, and historical development across geographic space.

Defining the Cultural Landscape

The term cultural landscape refers to the visible imprint of human activity on the physical environment. This foundational idea in human geography emphasizes that landscapes are not purely natural; they are shaped by people’s choices, values, technologies, and interactions with the physical world.

Cultural Landscape: The combined result of physical features and human cultural expressions that are visible on the land.

Human geographers rely on cultural landscapes to interpret how societies organize space, modify environments, and express identity. Because landscapes change over time, they offer key evidence of cultural processes and spatial patterns.

Key Components of Cultural Landscapes

Cultural landscapes are composed of both environmental elements and cultural factors, which interact to form distinctive spatial signatures.

Physical features

Landforms such as mountains or plains

Natural resources like rivers, forests, and fertile soils

Climate patterns that shape agricultural and settlement choices

Human cultural expressions

Architectural styles and building materials

Settlement layouts, from grid-pattern cities to dispersed rural villages

Economic practices such as agriculture, industry, or tourism

Religious features including temples, cemeteries, or sacred sites

Linguistic markers like signage and place names

These features combine to produce landscapes that communicate how communities live, what they value, and how they adapt to their surroundings.

How Geographers Interpret Cultural Landscapes

Cultural landscapes act as a text that can be read by geographers. Observation, mapping, and spatial analysis reveal cultural patterns embedded in the landscape.

Geographers evaluate cultural landscapes using several approaches:

Spatial analysis to examine distributions and patterns of cultural features

Historical interpretation to trace changes due to migration, technology, or political shifts

Comparative study of landscapes across regions to identify cultural similarities or differences

Environmental analysis to understand how physical conditions influence cultural expression

These methods help geographers identify relationships between culture and the environment that may not be visible at first glance.

A cultural landscape is produced through ongoing human–environment interaction as people adapt to, use, and reshape the land.

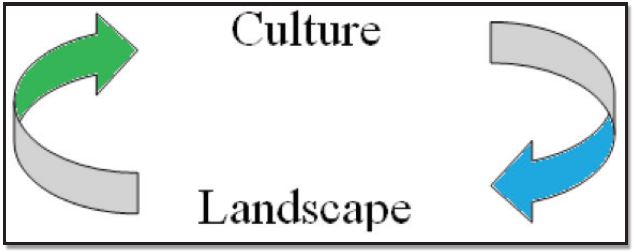

This diagram illustrates the reciprocal relationship between culture and landscape. Cultural values and practices shape how people modify physical environments, while existing landscapes influence cultural choices. It visually reinforces the idea that cultural landscapes are co-produced by people and place. Source.

Cultural Landscapes as Evidence of Human–Environment Interaction

The concept of a cultural landscape directly reflects human–environment interaction, a core theme of AP Human Geography. Landscapes show how cultural groups modify natural settings to meet needs or express beliefs.

Examples of this interaction include:

Converting forests into farmland

Constructing irrigation systems in arid regions

Building transportation networks such as roads, ports, or railways

Creating parks, plazas, and monuments that reflect political or social values

Such modifications demonstrate how societies respond to physical constraints and opportunities while leaving lasting marks on the landscape.

Why Cultural Landscapes Matter in Human Geography

Cultural landscapes allow geographers to identify cultural regions and understand how culture varies across space. Because landscapes are shaped by cultural processes such as diffusion, migration, and technological change, they reveal:

Cultural identity shown through architecture, land use, or symbolism

Economic structure reflected in agricultural fields, factories, or commercial areas

Political organization visible in borders, administrative buildings, or planning decisions

Social values expressed in religious architecture, public spaces, or memorials

These landscapes serve as living records of cultural development and social organization.

Types of Cultural Landscapes

Geographers often categorize cultural landscapes based on the processes that created them. While classifications may vary, they commonly include:

Designed landscapes

Landscapes intentionally shaped for aesthetic or functional purposes

Examples include planned cities, gardens, and ceremonial spaces

Vernacular landscapes

Everyday landscapes shaped gradually through local traditions and needs

Housing types, agricultural areas, and community layouts fit here

Historic landscapes

Landscapes preserved or recognized for their cultural or historical significance

Battlefields, heritage districts, and ancient settlement sites fall into this category

Each type highlights different aspects of how culture becomes embedded in the land.

Terraced rice fields in mountainous regions, where steep hillsides are carved into stepped paddies and lined with villages, are iconic examples of cultural landscapes.

This photograph shows the Batad Rice Terraces in the Philippine Cordilleras, a UNESCO-recognized living cultural landscape. The image highlights how farmers engineered steep slopes into layered paddies integrated with settlements and footpaths. Although it includes a specific UNESCO context beyond the syllabus, it clearly demonstrates how human labor and local ecology shape cultural landscapes.Source.

Reading Cultural Landscapes Through Material and Nonmaterial Culture

A cultural landscape contains both material culture—physical, tangible cultural expressions—and nonmaterial culture, which includes values and beliefs that influence spatial patterns.

Material Culture: Physical objects, structures, and spaces created by a society, such as buildings, tools, and infrastructure.

Material culture is the most directly visible in landscapes, but nonmaterial culture shapes decisions about how space should be used or organized. For example, religious beliefs may determine the placement of sacred structures, while economic values may influence land-use zoning.

Understanding both cultural dimensions allows geographers to interpret cultural landscapes with greater depth and accuracy.

Cultural Landscapes as Dynamic Spaces

Cultural landscapes constantly evolve as societies change. New technologies, demographic shifts, political transformations, and cultural diffusion all leave visible traces. This dynamism means that landscapes capture change over time as well as continuity.

Geographers study these transformations to understand cultural resilience, adaptation, and the forces shaping spatial organization.

Historic and sacred sites—such as temple complexes, pilgrimage valleys, or ancient ruins embedded in everyday farmland—also form cultural landscapes where past and present uses overlap on the same land.

This view of the Bamiyan Valley shows a cultural landscape where agricultural fields, cliffs, and archaeological remains coexist. It demonstrates how historic sacred features become embedded within everyday working land. Although it includes specific local geological and heritage details, it clearly visualizes the combination of cultural and physical features that define a cultural landscape. Source.

Cultural Landscapes in AP Human Geography

The AP Human Geography course emphasizes cultural landscapes because they provide a tangible lens for understanding abstract cultural processes. They offer real-world evidence of:

How culture shapes space

How human–environment interaction varies

How cultural identities become visible

How political, economic, and social systems influence land use

Recognizing and interpreting these landscapes is essential for analyzing cultural patterns and processes across scales.

FAQ

Cultural landscapes include visible human modifications, whereas natural landscapes consist only of physical features shaped by environmental processes.

Cultural landscapes show how people adapt to or transform the environment through features such as settlements, agricultural fields, routes, and religious structures.

Natural landscapes lack these imprints of human activity, although they still influence the type and form of cultural features that eventually appear.

Cultural landscapes reveal clusters of similar practices, architectural styles, land-use patterns, or symbolic features that can indicate shared cultural identities.

Geographers use these patterns to outline cultural regions because consistent traits across space show how groups organise, value, and interact with their environment.

This allows researchers to infer cultural boundaries even when political or linguistic borders are unclear.

Variation often results from differences in:

• Local physical conditions such as slope, soil type, or access to water

• Distinct community traditions or belief systems

• Resource availability that shapes building materials or farming practices

Neighbouring areas may therefore express different cultural identities even with similar climates, producing highly localised landscape patterns.

Landscapes retain traces of earlier cultural groups, including abandoned structures, old field systems, or repurposed buildings.

By examining these layers, geographers can identify processes such as migration, colonisation, economic shifts, or cultural replacement.

This makes cultural landscapes valuable archives, revealing change even when written records are limited or absent.

Authorities may shape landscapes intentionally through planning, zoning, monumental architecture, or land redistribution.

Landscape features such as public squares, government buildings, military sites, and transport routes can reflect political priorities or control.

Power can also determine which cultural expressions are promoted, preserved, or erased, influencing whose identity becomes visible in the landscape.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define the term “cultural landscape” and explain how one visible feature in a cultural landscape can reflect the beliefs or practices of a society.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of “cultural landscape” (e.g., a landscape shaped by the interaction of physical features and human cultural expressions).

1 mark for identifying a visible cultural feature (e.g., religious building, agricultural practice, settlement pattern).

1 mark for explaining how that feature reflects cultural beliefs or practices (e.g., a temple indicates the importance of religion; terraced fields reflect agricultural adaptation and tradition).

Maximum: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of cultural geography, analyse how both physical features and human cultural expressions combine to create a cultural landscape. In your answer, refer to at least two different types of cultural features and explain how geographers use these landscapes to interpret cultural patterns.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for describing how physical features contribute to the formation of cultural landscapes (e.g., climate, topography, natural resources shaping land use or settlement).

1–2 marks for describing how human cultural expressions contribute to the landscape (e.g., architecture, agricultural systems, religious structures, linguistic markers).

1–2 marks for explaining how geographers use these combined features to interpret cultural patterns (e.g., identifying cultural identity, historical processes, economic organisation, or spatial patterns).

Answers showing a clear analytical link between the features and their cultural significance should receive marks at the higher end.

Maximum: 6 marks.