AP Syllabus focus:

‘Attitudes toward ethnicity and gender, women’s workforce roles, ethnic neighborhoods, and indigenous lands all shape spatial use in a society.’

Human societies organise and use space in ways influenced by cultural beliefs about ethnicity, gender, and social roles. These beliefs guide settlement patterns, mobility, resource access, and social interaction, creating recognisable spatial structures visible at multiple geographic scales.

Ethnicity, Identity, and Spatial Patterns

Ethnicity shapes how groups form communities, use territory, and maintain cultural identity within larger societies. Ethnic groups often cluster to preserve shared language, traditions, or social support systems, producing spatial patterns that reflect both cultural choices and historical circumstances.

The term ethnicity refers to shared cultural traits and ancestry that distinguish a group from others.

Ethnicity: A cultural classification based on shared ancestry, traditions, language, or heritage that differentiates one group from another.

Ethnic identity becomes spatially expressed through neighbourhood formation, land rights, migration flows, and community institutions that anchor identity to particular locations.

Spatial Expressions of Ethnicity

Ethnic neighbourhoods

Urban areas where people of similar ethnic backgrounds cluster for cultural, social, or economic reasons.Cultural institutions

Religious centres, markets, and community halls strengthen place-based identity.Historical segregation

Past discriminatory policies can create persistent spatial divisions that continue to influence housing, access to services, and economic opportunities.

These patterns shape how groups experience urban and rural environments and how they interact with other cultural communities.

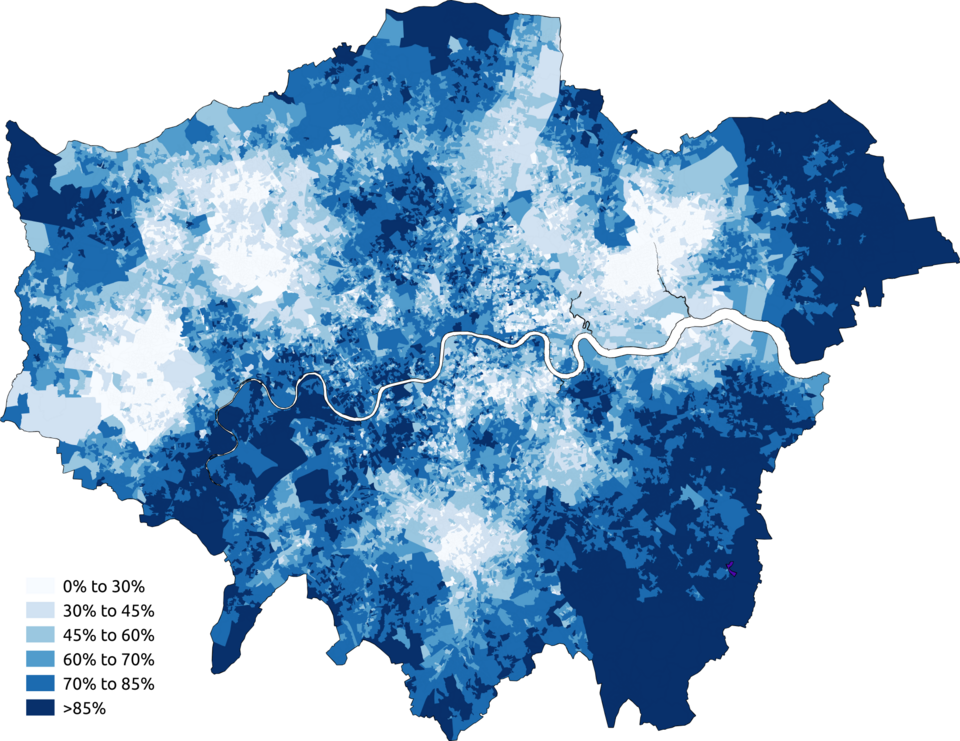

This map displays the uneven spatial distribution of white-identifying residents across Greater London, revealing patterns of ethnic clustering and separation. The contrasting shades visually reinforce how ethnicity shapes neighbourhood formation. The map includes extra detail by focusing specifically on the white population rather than showing all ethnic groups together. Source.

Indigenous Lands and Spatial Rights

Indigenous groups maintain longstanding cultural, spiritual, and historical connections to specific territories. Their land-use practices and territorial rights shape spatial patterns, especially in regions where indigenous claims influence resource management, governance, or cultural preservation.

Indigenous territories often function as spaces where cultural traditions, environmental knowledge, and political authority converge.

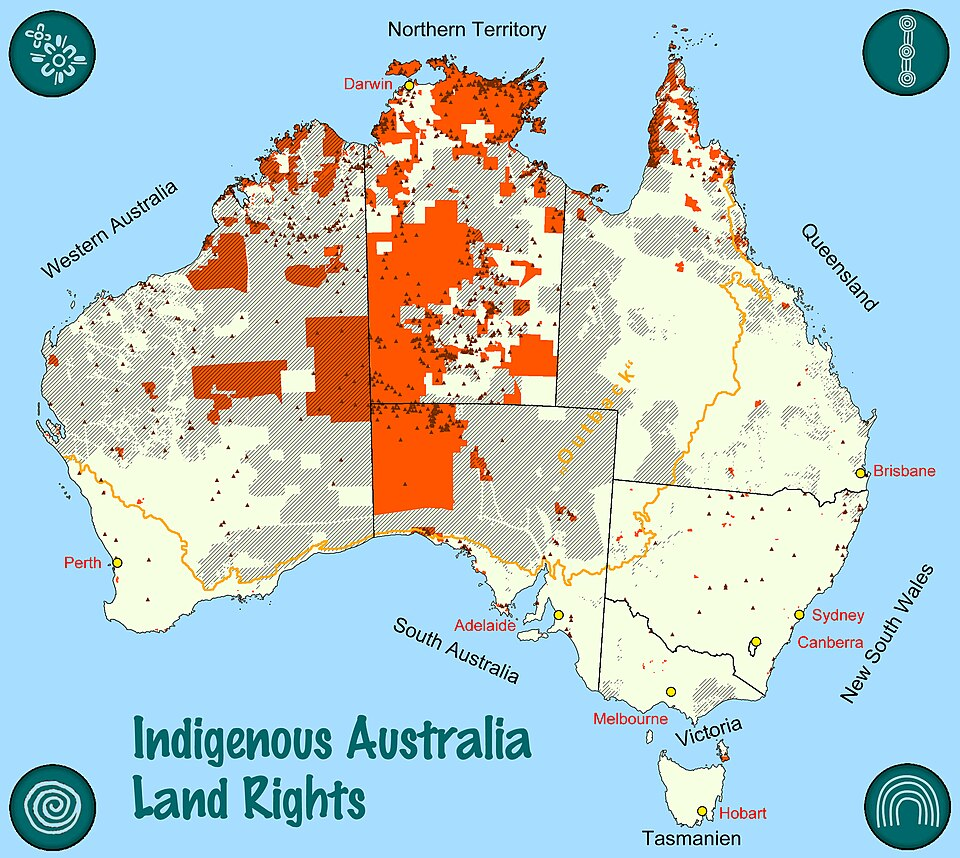

This map shows legally recognised Indigenous land rights and native titles across Australia, illustrating how cultural and political claims shape control of geographic areas. These spatial patterns reflect deep historical and cultural relationships to land. The detailed legend provides additional categories beyond syllabus requirements but aids interpretation of territorial variation. Source.

Key Spatial Factors Shaped by Indigenous Presence

Control over natural resources such as forests, rivers, or agricultural land

Protection of sacred sites and culturally significant landscapes

Governance systems that organise land according to traditional laws or collective ownership

Restricted access zones intended to preserve ecological and cultural integrity

These spatial dynamics reflect deep-rooted cultural relationships with the land, influencing regional planning and conservation.

Gender, Culture, and Use of Space

Gender norms shape how individuals navigate and occupy space within homes, workplaces, and public environments. Cultural expectations regarding gender roles influence mobility, labour patterns, and the design of spaces used for work, education, and domestic life.

The term gendered spaces refers to areas shaped by cultural expectations about appropriate behaviour, presence, or roles for men and women.

Gendered Spaces: Physical or social spaces where cultural norms designate different roles, behaviours, or levels of access for men and women.

Gendered patterns reveal how societies structure daily activities and define who belongs where within a cultural landscape.

How Gender Norms Influence Spatial Patterns

Mobility restrictions

Some cultures limit women’s movement in public spaces or require male accompaniment.Workforce roles

Gendered labour divisions create distinct patterns in industrial, agricultural, and service-sector locations.Public versus private zones

Homes, workplaces, and streets may reflect gendered expectations about privacy, caregiving, or social interaction.Safety and accessibility

Lighting, transportation routes, and public design often reflect assumptions about which groups use space at particular times.

These factors collectively shape the lived experience of gender across landscapes.

A normal sentence is introduced here to ensure clarity between conceptual sections before proceeding.

Women’s Workforce Roles and Spatial Organisation

Women’s participation in the workforce has significant spatial implications.

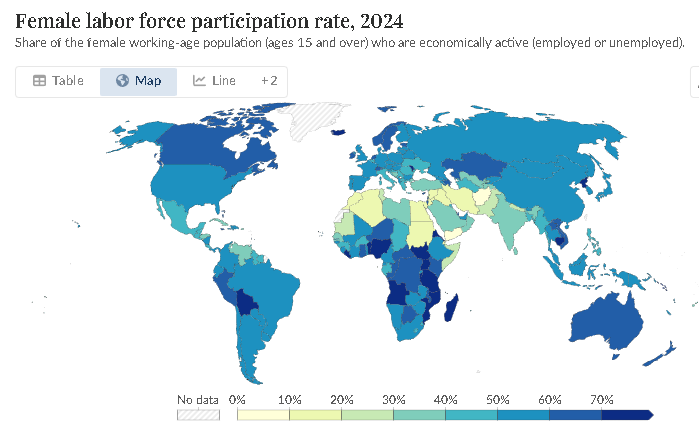

This world map shows where legal restrictions limit the types of jobs women can hold, demonstrating how gender norms are formalised into labour regulations. Such barriers create distinct spatial patterns in women’s workforce participation. The map includes additional classification detail beyond syllabus requirements, shown through colour-coded country categories. Source.

Spatial Effects of Women’s Workforce Participation

Changes in commuting flows

Increased workforce participation influences transportation demand and urban connectivity.Growth of childcare and social services

Rising demand for supportive institutions affects commercial and residential zoning.Shifts in household spatial organisation

Dual-income households may alter living arrangements, home-work proximity, and mobility routines.Economic diversification of neighbourhoods

Areas with growing female employment may develop new service sectors or commercial functions.

These changes reflect evolving gender norms and contribute to broader transformations in cultural landscapes.

Interactions Between Ethnicity, Gender, and Spatial Inequality

Ethnicity and gender intersect to produce varied spatial experiences and access levels within societies. Marginalised groups may face limited access to housing, education, transportation, or employment, reinforcing spatial inequality across urban and rural regions.

How Intersecting Identities Shape Spatial Outcomes

Differential access to public services

Ethnic minorities or women may experience disparities in healthcare, schooling, and transportation networks.Housing patterns

Combined ethnic and gender discrimination can influence affordability, location, or safety of available housing.Economic zones and workforce segregation

Women and ethnic minorities may be concentrated in specific industries or geographic areas due to cultural expectations or structural barriers.Political representation and land rights

Access to decision-making power affects whose spatial needs are prioritised in planning and development.

These patterns highlight how cultural attitudes toward ethnicity and gender shape the organisation and use of space throughout societies.

FAQ

Ethnic neighbourhoods often shift as migration flows, economic opportunities, and housing markets evolve. Early clusters may disperse as later generations achieve upward mobility or move into more diverse areas.

However, new arrivals may form fresh clusters in the same locations, creating a cycle of changing ethnic presence while maintaining the area’s cultural character in different ways.

Safety concerns influence when and where women feel comfortable travelling. Poor lighting, limited public transport, or isolated areas may restrict women’s mobility even when no formal rules exist.

This can create informal gendered patterns in urban space, shaping daily routines such as commuting, leisure, and use of public facilities.

Indigenous claims are usually tied to ancestral territories rather than recent migration. These claims emphasise cultural stewardship, sacred sites, and collective ownership systems.

As a result, indigenous spatial patterns tend to be more territorially anchored, covering larger land areas and including resource management practices specific to cultural heritage.

Segregation can arise when cultural norms encourage men and women to pursue different types of work. Over time, this concentrates each gender in distinct sectors or regions.

This division may be reinforced by schooling systems, informal expectations, or policies that restrict access to certain jobs, shaping geographic patterns of employment.

People who experience both ethnic and gender marginalisation may face compounded barriers in housing, employment, and public services.

For example:

Limited access to transport may disproportionately affect ethnic minority women.

Housing shortages may push these groups into less safe or less well-served areas.

Employment discrimination may concentrate them in lower-paid sectors tied to specific locations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how gendered spaces reflect cultural expectations within a society.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that gendered spaces arise from cultural norms about appropriate roles or behaviours for men and women.

1 mark for describing how these norms influence the design, use, or accessibility of specific locations (e.g., workplaces, public spaces, or domestic areas).

1 mark for linking the spatial pattern to broader cultural beliefs about gender, safety, labour, or social interaction.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using an example, analyse how ethnicity can influence spatial patterns in an urban environment. In your answer, refer to at least two different spatial factors.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for correctly defining or describing ethnicity as a cultural or ancestral identity.

1 mark for identifying at least one spatial pattern shaped by ethnicity (e.g., ethnic neighbourhoods, clustering, service areas, or community institutions).

1 mark for identifying a second spatial factor influenced by ethnicity (e.g., access to housing, segregation, land rights, or mobility patterns).

1–2 marks for explaining how historical, cultural, or socio-economic processes led to the observed spatial pattern.

1 mark for clarity, depth, and accurate use of geographic terminology.