AP Syllabus focus:

‘Landscape features and resource use reflect cultural beliefs and identities, shaping how societies organize and use space.’

Cultural identity shapes how people perceive, organise, and interact with space, producing distinct spatial patterns that express shared beliefs, values, traditions, and social structures across landscapes.

Culture, Identity, and Spatial Expression

Culture plays a central role in determining how groups understand space, assign meaning to locations, and establish behavioural expectations within environments. The resulting spatial patterns reflect collective identities and communicate the norms of cultural communities. These patterns influence everything from settlement structure to the symbolic use of buildings, reflecting the lived experience of a group.

The term cultural identity refers to the shared sense of belonging and collective characteristics that define a cultural group. These identities become embedded in landscapes through everyday practices, visible structures, and spatial organisation.

Cultural Identity: The shared sense of belonging and collective traits—such as beliefs, values, and traditions—that define membership in a cultural group.

Because identity influences how groups perceive their environment, cultural landscapes are both expressions of identity and tools for reinforcing it.

How Culture Shapes the Use of Space

Cultural norms guide how societies divide, manage, and assign meaning to places. Spatial behaviour is rarely neutral; it reflects deep-seated cultural beliefs about community, privacy, gender, religion, and social hierarchy. Geographers examine these spatial expressions to understand the relationship between culture and place-based organisation.

Key Ways Culture Influences Spatial Use

Sacred versus secular spaces

Cultural groups distinguish between holy, ceremonial, and everyday areas, influencing land allocation and architectural forms.Public versus private spaces

Beliefs about social interaction shape the design of homes, markets, plazas, and gathering areas.

This image of Cleveland’s Public Square demonstrates how cultural expectations for community interaction shape the design of shared civic environments. Landscapes like this are intentionally structured to promote gathering, accessibility, and symbolic visibility. Architectural context surrounding the square provides additional detail beyond the scope of the AP syllabus but enhances conceptual understanding. Source.

Gendered spaces

Cultural norms may influence which spaces are associated with men or women and how each group is permitted to move through them.Hierarchy and social order

Spatial layout may reinforce class, caste, or status distinctions through proximity to central or prestigious locations.

These cultural preferences become visible across the landscape, producing identifiable patterns in settlement distributions, street networks, and building arrangements.

The Role of Symbolism in Cultural Landscapes

Cultural identity is often communicated through symbolic spaces—locations imbued with cultural meaning. These places function as markers of group presence and reinforce shared historical narratives or religious beliefs. Symbolic features may be material, such as monuments, or spatial, such as the orientation of buildings.

Symbolic Landscape: A landscape containing features that convey cultural meanings or express shared values, histories, or identities of a group.

Symbolic landscapes allow groups to reinforce social unity, articulate power, and express their worldview through spatial design.

Resource Use and Cultural Beliefs

The ways societies utilise natural resources are shaped not solely by economic concerns but also by cultural values and environmental knowledge.

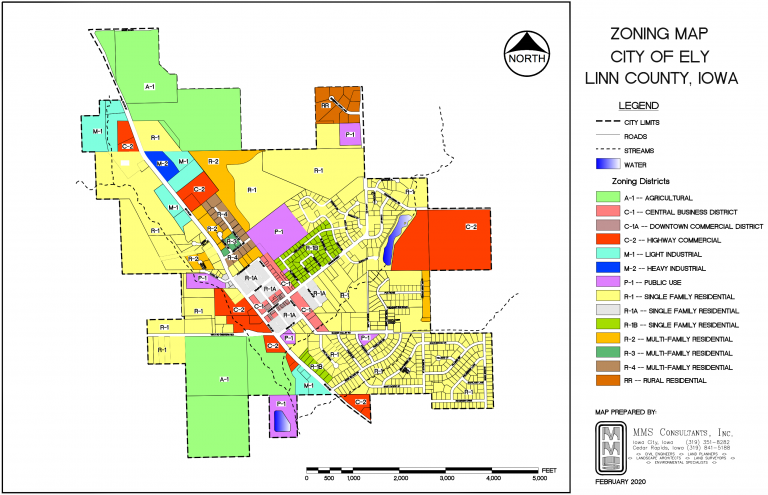

This zoning map demonstrates how cultural values and planning principles manifest in the allocation of residential, commercial, and industrial spaces. Such maps reveal how societies translate beliefs about community organisation, environmental stewardship, and economic activity into spatial rules. The detailed parcel boundaries go beyond syllabus requirements but assist with visual interpretation. Source.

Cultural Beliefs Guiding Resource Use

Agricultural practices

Crop choices, field systems, and land tenure systems are tied to cultural traditions and environmental worldviews.Environmental stewardship

Some societies emphasise conservation or sacredness of land, affecting logging, hunting, and water use.Technological preferences

Cultural acceptance or rejection of certain technologies influences settlement density, energy use, and industry.Collective versus individual resource management

Cultural expectations shape whether land is shared or privately owned, influencing spatial organisation.

These practices create distinctive resource landscapes that reflect deeply embedded cultural assumptions.

Cultural Identity and Territoriality

Territoriality—the control of space to express power or identity—is a key cultural process shaping spatial organisation. Groups use territorial markers to define boundaries, reinforce identity, and regulate interaction.

Territoriality: The attempt by an individual or group to influence, affect, or control people, phenomena, and relationships through the deliberate organisation and assertion of control over geographic area.

Territorial patterns may appear in neighborhood boundaries, religious complexes, ethnic districts, or governance structures that regulate movement and land access.

The Chinatown Gate in London marks the entrance to a culturally distinct district, symbolising collective identity and territorial presence. Its architectural style and inscriptions express heritage and reinforce community belonging. Additional urban surroundings in the background offer context beyond syllabus expectations. Source.

A normal sentence is needed here to maintain clarity and flow between conceptual elements before moving to further content.

Cultural Identity and the Built Environment

Built environments—houses, religious structures, public squares, and markets—serve as physical records of cultural identity. Architectural style, spatial organisation, and material choices reveal the values and societal roles shaping cultural life.

Features that Express Identity in Built Space

Building orientation

Some cultures orient structures toward sacred directions or environmental features.Residential patterns

House layout may reflect gender roles, kinship networks, or privacy norms.Commercial and civic spaces

Markets, temples, halls, and plazas often sit at the heart of cultural identity, acting as centres for ritual, trade, or governance.Neighbourhood clustering

Groups may cluster to maintain linguistic, religious, or ethnic identity, generating distinct cultural districts.

These spatial choices communicate how a group understands community, belonging, and social interaction.

Identity, Mobility, and Spatial Behaviour

Cultural identity influences how people move through space. Movement patterns—daily routes, gendered mobility norms, or ritual journeys—reflect cultural expectations about behaviour and belonging. Geographers analyse these patterns to understand how identity structures mobility.

Cultural Factors Shaping Mobility

Acceptance or restriction of women’s movement

Ritual journeys, pilgrimages, or processions

Social expectations about public behaviour

Cultural norms shaping commuting or work patterns

Mobility patterns demonstrate how identity and culture shape lived spatial experience, embedding cultural meaning into everyday movement.

FAQ

Cultural groups often embed hierarchy in subtle spatial cues such as seating arrangements, access routes, or visibility from central spaces.

These cues communicate who holds authority or prestige without relying on monumental structures.

Examples include restricted courtyards, elevated meeting areas, or pathways that require lower-status individuals to approach leaders from specific directions.

Migration introduces new cultural practices that interact with existing spatial norms.

This can lead to:

Hybrid spaces blending old and new traditions

Repurposed buildings gaining new cultural meanings

Changes in neighbourhood clustering as new groups settle

Over time, these shifts create more complex cultural identities embedded in everyday spatial behaviour.

Festivals and rituals often transform ordinary spaces into ceremonial or symbolic environments.

Streets become procession routes, markets convert to gathering spaces, and squares host cultural performances.

These temporary changes highlight how cultural identity is dynamic, revealing deeper meanings attached to space even outside formal religious or political contexts.

Territorial preferences depend on history, social organisation, and perceived threats.

Groups with histories of displacement or marginalisation may emphasise clear boundaries to protect identity.

Others with more flexible social structures may rely on symbolic markers rather than strict spatial control.

Commercial zones often reflect cultural tastes, values, and social interactions.

Shops, markets, and food districts can become expressions of community identity, especially when goods and services cater to specific cultural groups.

Over time, these areas may evolve into recognised cultural districts that blend economic activity with shared heritage.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how cultural identity can influence the organisation of public and private spaces within a settlement.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that cultural identity shapes expectations about how space should be used or divided (e.g., norms about interaction or privacy).

1 mark for describing a spatial distinction influenced by cultural beliefs (e.g., layout of plazas, markets, or household compounds).

1 mark for linking the spatial pattern to the cultural values that motivate it (e.g., emphasis on community, family structure, or social hierarchy).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how symbolic landscapes and territoriality together contribute to expressing cultural identity. Use a real or hypothetical example to support your explanation.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for defining or describing symbolic landscapes as spaces conveying cultural meaning or identity.

1 mark for defining or describing territoriality as the assertion of control or presence over a geographic area.

1–2 marks for explaining how the two concepts interact to strengthen expressions of cultural identity.

1–2 marks for a well-developed example showing these processes in practice (e.g., an ethnic district, religious precinct, or culturally marked boundary).

1 mark for clarity, coherence, and accurate use of geographic terminology.