AP Syllabus focus:

‘Voting districts are internal political boundaries that affect election outcomes; identify how district patterns shape representation at different scales.’

Voting districts structure how people are grouped for elections, shaping political power by influencing representation, electoral competitiveness, and how communities’ interests are translated into government decision-making.

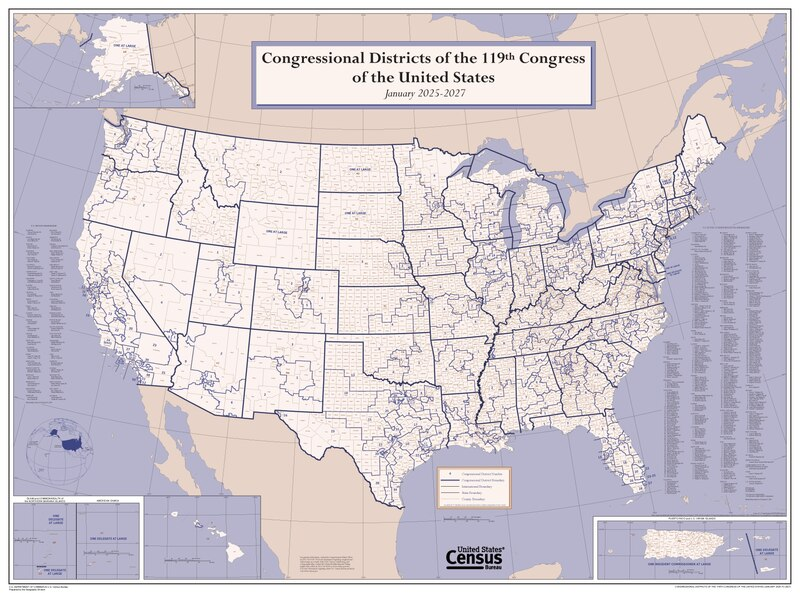

Congressional districts of the 119th U.S. Congress illustrate how the country is divided into geographic units, each electing one representative to the House. The boundaries show how every area is assigned to exactly one district, demonstrating the role of internal political boundaries in structuring representation. U.S. territories appear with non-voting delegate districts, which exceeds AP requirements but offers broader context. Source.

Understanding Voting Districts

Voting districts are the internal political subdivisions used to elect representatives to legislative bodies at local, state, and national levels. When a voting district is created or altered, it changes how populations are grouped, influencing whose voices are amplified or diluted in the political process. These districts are central to understanding how political geography affects representation.

Voting District: A geographically defined area from which residents elect representatives to a legislative body.

A voting district's size, shape, and demographic composition all affect political outcomes because they determine how many voters of particular backgrounds, interests, or ideologies are grouped together. This makes voting districts one of the most powerful internal political boundaries in shaping governance.

The Spatial Organization of Representation

How District Patterns Influence Representation

District patterns influence representation by shaping who is included in each district and how their votes count. Because legislative seats are typically allocated on a district-by-district basis, the way boundaries are drawn directly impacts the distribution of political power.

This map of New York’s congressional districts shows how one state is subdivided into numbered voting districts, each electing a representative to the U.S. House. The colors and labels highlight how boundary choices group populations into distinct constituencies, shaping representation. District numbers and their historical time frame exceed AP syllabus needs but effectively illustrate internal political boundaries. Source.

District design affects representation in several key ways:

Population Equality

Most systems require districts to contain roughly equal populations. This principle, known as “one person, one vote,” ensures that votes carry similar weight across districts.Community Cohesion

District boundaries may split or preserve communities of interest, which are groups with shared cultural, economic, or political identities. Keeping such communities intact increases the likelihood that their needs are represented.Competitiveness

Some district patterns create competitive elections, while others produce “safe seats,” where one party or group consistently wins. The competitiveness of a district can influence voter turnout, campaign strategies, and policy priorities.

Multiscale Impacts on Representation

Voting districts operate at multiple scales, which shapes political outcomes differently across levels of government:

Local Scale

City council wards or school board districts influence neighborhood-level governance, resource allocation, and local decision-making.State Scale

State legislative districts affect laws on education, taxation, transportation, and public health, often shaping daily life more than national policies.National Scale

Congressional districts determine representation in the national legislature, influencing national policy direction, federal funding, and party control of government.

Across all scales, the layout of districts reflects both demographic patterns and political interests, making district design a highly influential geographic process.

Processes in Creating and Adjusting Voting Districts

The Redrawing of Boundaries

District boundaries are periodically updated to reflect population changes, typically following a census. This process directly affects representation because population growth or decline shifts the balance of political power across regions.

Key steps in creating or altering districts include:

Mapping population distribution using census data to determine how many districts a state or locality requires.

Allocating populations into districts that meet legal requirements for equal population and compliance with civil rights protections.

Adjusting shapes to account for geographical features, municipal boundaries, or community cohesion where appropriate.

Even when designed with neutrality, the drawing of districts can reshape political power simply by shifting how populations are grouped.

Legal and Institutional Constraints

Voting district creation is governed by legal guidelines intended to protect fair representation. These include:

Equal Population Requirements

Districts must be roughly equal in population so each representative corresponds to a similar number of constituents.Protection of Minority Voting Rights

Districts cannot be drawn in ways that dilute the voting power of racial or ethnic minorities, a principle grounded in the Voting Rights Act in the United States.Contiguity and Compactness

Many systems require districts to be geographically connected and reasonably compact, although interpretations vary widely.

These rules create a baseline for equitable representation but still leave significant room for political influence.

Political Geography and the Effects of District Patterns

Spatial Patterns and Their Political Impact

The shape of a district is more than a line on a map; it reflects historical settlement patterns, demographic clusters, and political strategies. District maps often reveal the interplay between geography and political behavior:

Urban areas may be divided into multiple districts to distribute dense populations or consolidated into fewer districts that concentrate political power.

Rural districts may be geographically large but sparsely populated, often resulting in different policy priorities and representational styles.

Growing regions may gain new districts, increasing political influence, while shrinking regions may lose seats.

District patterns therefore help explain shifts in legislative control, emerging political coalitions, and long-term changes in voting behavior.

Representation and Voter Influence

The way boundaries are drawn affects whether different demographic groups feel represented or marginalized. District patterns can:

Enhance representation by grouping like-minded or culturally cohesive communities.

Weaken representation by splitting communities across districts.

Alter political engagement by making elections more or less competitive.

Because voting districts shape the connection between people and their government, they are a foundational element of political geography and essential to understanding how electoral systems translate population geography into political power.

FAQ

Most voting districts are reviewed every ten years following a national census, as population changes can disrupt equal representation.

In some countries or states, authorities may conduct mid-cycle adjustments if population shifts are large enough to create significant imbalances.

Occasionally, legal challenges or court orders can trigger additional redraws when existing districts violate fairness or minority-protection rules.

Voting districts may need to consider natural features such as rivers, mountains, or coastlines, which can act as practical boundaries.

Human-made features also matter, including major roads, municipal borders, or school catchment lines.

Some regions incorporate community cohesion by keeping culturally or economically linked neighbourhoods within the same district.

Communities of interest represent groups with shared concerns or identities, such as ethnic groups, economic sectors, or cultural communities.

Keeping these communities intact within a district helps ensure their collective needs are represented rather than diluted across multiple districts.

This approach can strengthen political engagement and improve the responsiveness of elected representatives.

Demographic data helps identify population densities, age structures, ethnic compositions, and socioeconomic patterns.

This information guides map-makers in achieving population equality while also complying with minority protection requirements.

Such data can reveal where districts may need to be expanded, contracted, or reconfigured to reflect real population changes.

Rapid population growth can cause severe imbalances between districts within a short period, reducing representational fairness.

Authorities may struggle to keep pace with shifting populations, leading to districts that become outdated before the next census.

Urban sprawl can also blur clear boundaries, requiring careful decisions about where to divide dense and diverse communities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how the principle of “one person, one vote” shapes the creation of voting districts within a state.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying the principle as requiring districts to have roughly equal populations.

• 1 mark for explaining that this ensures each vote has similar weight across districts.

• 1 mark for linking the principle to fair or equitable representation in legislative bodies.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of political geography, analyse how the design of voting district boundaries can influence patterns of political representation at different scales.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying that district boundaries determine which populations are grouped together.

• 1 mark for explaining an effect at the local scale (e.g., neighbourhood representation or resource allocation).

• 1 mark for explaining an effect at the state scale (e.g., influence over state-level policymaking).

• 1 mark for explaining an effect at the national scale (e.g., shaping party control in a national legislature).

• 1 mark for describing how boundary choices can enhance or weaken representation of specific communities or interests.

• 1 mark for showing a clear analytical link between boundary design and political outcomes (e.g., competitiveness, safe seats, or voter influence).