AP Syllabus focus:

‘Redistricting can change internal boundary lines and affect election results at various scales; explain how shifting boundaries can change patterns on maps and in data.’

Redistricting adjusts electoral boundaries within states, reshaping how populations are grouped for representation. These shifts influence voting outcomes, political power, and spatial patterns observable across multiple geographic scales.

Redistricting and Its Geographic Foundations

Redistricting refers to the periodic redrawing of internal political boundaries to reflect population changes. In the United States, this occurs every ten years following the census. Because redistricting reshapes how people are grouped into voting districts, it has significant effects on political representation, resource allocation, and spatial patterns of electoral outcomes across local, state, and national scales.

This map displays all U.S. congressional districts as distinct internal boundaries, illustrating how states are subdivided into numerous voting districts. It highlights the spatial organization underlying redistricting. The map contains no additional information beyond district shapes and outlines, keeping the visual focus clear. Source.

Redistricting: The process of redrawing electoral district boundaries to ensure equal population representation following demographic change.

Redistricting is inherently geographical because it determines how territory and population are organized for political decision-making. It also reflects the relationship between population distribution, urbanization, migration trends, and changing demographic patterns that evolve over time.

Why Redistricting Occurs

Redistricting is primarily driven by the constitutional requirement of “one person, one vote.” Electoral districts must contain roughly equal populations so that all citizens’ votes carry comparable weight. When population shifts—such as suburban growth, rural decline, or immigration-driven urban expansion—create imbalances, district boundaries must adjust.

Major demographic drivers requiring redistricting

Population growth or decline altering district size

Urbanization, shifting populations from rural to metropolitan areas

Migration, both domestic (e.g., Sun Belt growth) and international

Changes in population composition, especially age or ethnicity distributions

These drivers ensure that redistricting is not merely a political exercise but also a demographic and geographic one.

Scale Effects in Redistricting

The syllabus emphasizes that shifting boundaries can change patterns on maps and in data, and this occurs because redistricting reshapes political geography at multiple levels.

Local Scale

At the local scale, changes to voting districts immediately affect neighborhoods and communities.

A neighborhood may be split, combining it with areas that share fewer social or economic interests.

Community representation may strengthen or weaken depending on how boundaries group populations.

State Scale

At the state scale, redistricting determines representation in the state legislature and affects the balance of power.

Shifts can change which political party holds a majority.

Urban areas may gain seats if population density increases.

Rural regions with population decline may lose representation, altering the political landscape.

National Scale

At the national scale, redistricting shapes each state’s districts for the U.S. House of Representatives.

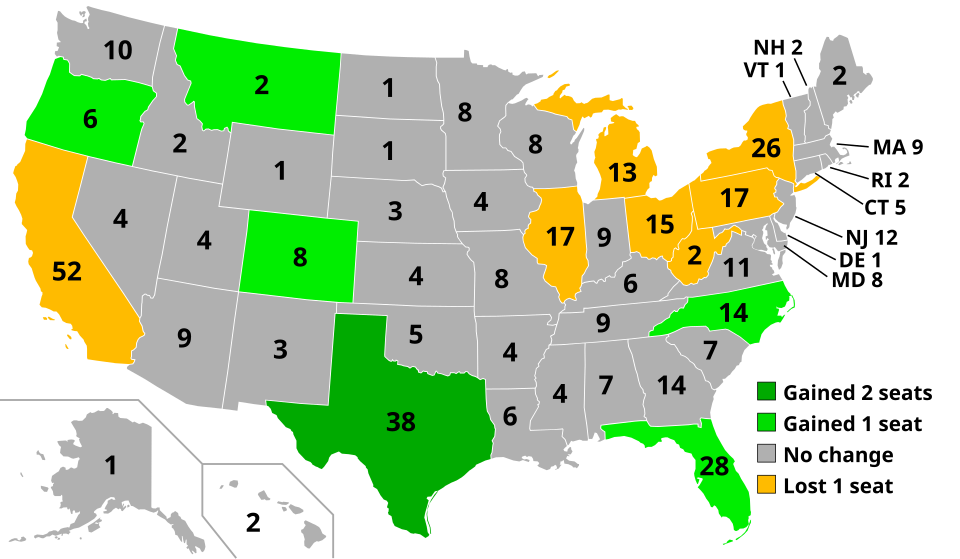

States gaining population may gain congressional seats, while states losing population may lose seats.

This reapportionment map shows how states gained or lost congressional seats after the 2020 census, demonstrating national-scale consequences of population change. It highlights geographic shifts that later require redistricting within states. Some color-coded numerical details extend slightly beyond the syllabus but directly support understanding scale effects on representation. Source.

Boundary changes can recalibrate how electoral maps display political competitiveness.

These scale effects reveal how redistricting transforms not only political representation but also how spatial data appear in maps, charts, and demographic summaries.

Geographic Consequences Visible in Maps and Data

Redistricting produces new spatial patterns, reshaping the geographic distribution of voters.

How shifting boundaries alter map patterns

Previously compact districts may become elongated or fragmented.

Urban and suburban regions may expand district coverage due to growth.

Minority-majority districts may strengthen representation when boundaries group communities with shared identities.

How redistricting affects data patterns

Vote-share percentages shift as populations are recombined.

Demographic data, such as ethnicity proportions or median income, change across newly drawn districts.

Statistical measures of district equity or competitiveness, such as the efficiency gap or compactness scores, may change significantly after maps are redrawn.

These changes illustrate why geographers analyze redistricting using qualitative maps, quantitative data, and spatial analysis tools.

Key Geographic Concepts Connected to Redistricting

Redistricting intersects with several foundational AP Human Geography concepts, illustrating how internal boundaries shape political processes.

Territoriality and power

The drawing of districts reflects territoriality, the attempt by political actors to influence and control space. Redistricting allows state governments to assert political authority by determining how voting power is distributed geographically.

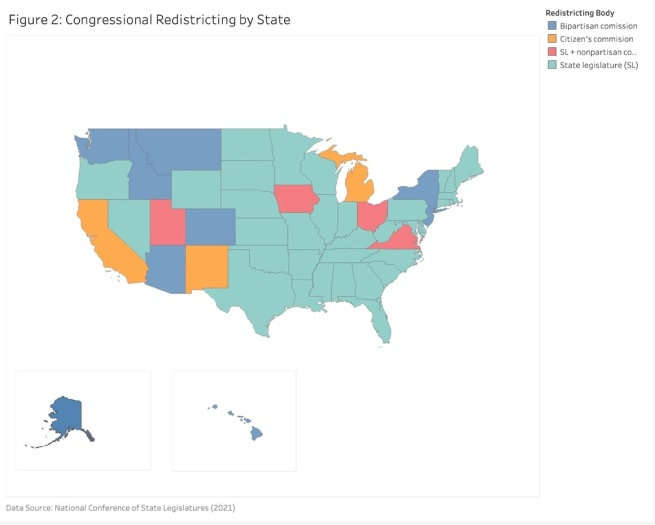

This map shows which type of institution—legislature or commission—controls congressional redistricting in each state, illustrating variations in political authority over internal boundaries. It reinforces how territoriality shapes decision-making in boundary drawing. The classification of commission types includes detail slightly beyond the syllabus but helps contextualize state-level governance differences. Source.

Spatial organization and representation

Redistricting affects the spatial organization of governance because it determines how representatives connect to their constituents.

Compact districts may facilitate easier communication and political accountability.

Fragmented districts can complicate representation and dilute community interests.

Community identity and cohesion

How boundaries are drawn can affirm or disrupt community identity. Districts that group together people with shared cultural or socioeconomic characteristics may strengthen representation, while those that split communities may weaken cohesion.

Processes and Criteria Used in Redistricting

Most redistricting efforts consider a set of geographic and political criteria. While laws vary by state, the following are common guiding principles:

Equal population across districts

Contiguity (districts must be one connected piece)

Compactness, minimizing irregular shapes

Preservation of communities of interest, including social, cultural, or economic groups

Respect for existing boundaries, such as counties or municipalities

Compliance with the Voting Rights Act, protecting minority representation

These criteria shape the geography of new districts while influencing electoral outcomes and representation across multiple scales.

FAQ

Redistricting can shift the demographic balance within districts by drawing boundaries that merge or split communities with distinct cultural, socioeconomic, or ethnic characteristics.

These demographic shifts may alter the visibility and influence of minority groups, change the composition of voters, or reshape the types of public services prioritised by elected representatives.

Redistricting does not directly cause demographic change, but the new boundaries can create incentives for population movement, particularly when residents seek districts that better reflect their political or community identity.

Governments and commissions use a wide range of spatial datasets to develop district maps, including:

• Census population counts and demographic breakdowns

• Housing density and urban growth patterns

• Transport infrastructure maps

• Voter registration and turnout data (where permitted)

These datasets help ensure districts meet population requirements while also reflecting geographic realities such as settlement patterns and community structure.

Suburbanisation often leads to uneven population growth, with suburban districts becoming disproportionately large by the end of a census cycle.

When redistricting occurs, these fast-growing suburban areas typically need to be divided into multiple districts, which can reduce the political dominance previously held by rural or inner-city areas.

The process can also increase suburban political influence, as newly formed districts may prioritise issues like transport, schooling, and housing development.

Yes. Even when districts have equal populations, the way boundaries are drawn can significantly affect minority influence.

For instance, minority groups can be split across several districts, lowering their electoral impact, or concentrated into a single district, increasing influence locally but reducing regional representation.

Such outcomes depend on how communities are spatially arranged and how map-drawers choose to combine or separate them.

Modern GIS software allows map-drawers to analyse demographic and electoral data with high precision, producing district proposals that would have been impossible using manual techniques.

These tools amplify scale effects by modelling how small changes in local boundaries ripple outward to affect state and national outcomes.

High-resolution spatial analysis also enables faster scenario testing, revealing how alternative district maps would alter voting patterns, demographic distributions, and political competitiveness.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how redistricting can change patterns on electoral maps at the state scale.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying that redistricting changes the boundaries of voting districts.

• 1 mark for explaining that these altered boundaries can shift which areas are grouped together politically.

• 1 mark for stating that these shifts can alter which political party or demographic group is more likely to win in specific districts, therefore changing the appearance and distribution of results on state-level electoral maps.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how redistricting reflects both geographic processes and political decision-making, and analyse how its effects differ across local, state, and national scales.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1 mark for describing redistricting as the redrawing of internal electoral boundaries.

• 1 mark for referencing demographic or geographic processes such as population change, urbanisation, or migration.

• 1 mark for recognising political decision-making, such as how state governments or commissions control boundary drawing.

• 1 mark for explaining effects at the local scale (e.g., neighbourhoods being split or grouped, affecting representation).

• 1 mark for explaining effects at the state scale (e.g., changes to legislative balance or district competitiveness).

• 1 mark for explaining effects at the national scale (e.g., seat gains or losses influencing overall political representation).