AP Syllabus focus:

‘Gerrymandering alters voting districts to influence election results at various scales; explain how boundary design can advantage certain groups or parties.’

Gerrymandering reshapes electoral districts to favor particular political interests, influencing representation, voter power, and election outcomes across multiple scales in ways that challenge democratic fairness and spatial equity.

Gerrymandering and Election Outcomes

Gerrymandering is a form of electoral boundary manipulation in which political actors redraw district lines to secure an advantage. Because voting districts are internal political boundaries, altering them reshapes how political power is distributed geographically and who ultimately gains representation. This process directly aligns with the syllabus emphasis on how boundary design can advantage certain groups or parties, making gerrymandering a significant political-geographic force.

When the practice first appears in a course context, students must understand that gerrymandering refers to the purposeful modification of district boundaries to favor one political group at the expense of another.

Gerrymandering: The intentional redrawing of electoral district boundaries to benefit a particular political party, group, or incumbent.

This practice affects political outcomes by changing the spatial arrangement of voters, often without altering population totals. It exemplifies how political power operates through territorial control, demonstrating the close link between boundary design and electoral geography.

How Gerrymandering Operates

Gerrymandering typically involves strategic manipulation of district shape, voter composition, and spatial arrangement to create partisan or group-based advantages. These strategies emerge during redistricting cycles, when new lines are drawn after population counts.

Key methods include:

Cracking: Dividing a concentrated group of voters across several districts to dilute their voting strength.

Packing: Concentrating opposition voters into a single district to reduce their influence in surrounding districts.

Stacking: Merging areas of dissimilar populations to create districts with predictable outcomes.

Hijacking and Kidnapping: Altering boundaries to disadvantage specific incumbents.

Each method highlights how districts that appear neutral on a map may embed deliberate political intentions. Because these decisions occur at various scales—from local school boards to national legislatures—they reveal how spatial arrangements shape political power.

Because seats, not raw vote totals, determine control of legislatures, manipulating where voters are grouped can significantly change election outcomes.

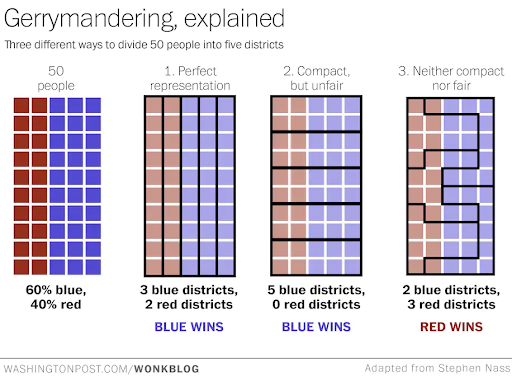

This diagram illustrates how the same voter distribution can yield different electoral outcomes depending on boundary design. It demonstrates how manipulating district lines can advantage particular parties or groups. The visual reinforces the principle that electoral geography shapes representation independently of vote totals. Source.

Spatial Patterns Produced by Gerrymandering

Gerrymandered districts often exhibit recognizable spatial patterns that differ sharply from those produced by organic or community-based boundary drawing.

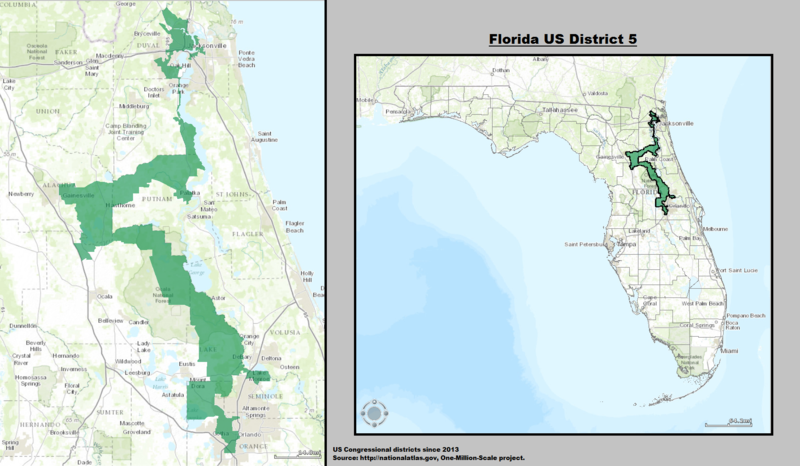

This map shows Florida’s 5th congressional district, an example of a highly irregular and elongated shape produced through gerrymandering. Its configuration demonstrates how districts may link distant communities to concentrate particular voters. Additional geographic information is included for context beyond the syllabus requirements. Source.

Common patterns include:

Highly irregular district shapes designed solely for political gain.

Disconnected or barely connected territories, sometimes linked through thin corridors.

Clusters of demographically similar voters, often resulting from packing or stacking.

Fragmented communities, where culturally or economically unified areas are split across multiple districts.

These spatial outcomes show how boundary design can reshape political landscapes even when population numbers stay constant.

Why Gerrymandering Matters for Representation

Because voting districts determine how people are grouped for elections, gerrymandering influences representation by shaping which voices are amplified or suppressed.

Important effects include:

Partisan Advantage: One party may secure disproportionately large numbers of seats relative to its share of votes.

Incumbent Protection: Manipulated districts reduce electoral competition and entrench political power.

Reduced Electoral Accountability: Safe seats created through packing or cracking weaken incentives for responsive governance.

Altered Demographic Representation: Minority populations may be either empowered or diluted depending on boundary design.

These outcomes relate directly to the AP focus on how gerrymandering influences election results at various scales—local, state, and national—by structurally shaping voter influence.

Gerrymandering and Spatial Scale

Scale is a foundational concept in AP Human Geography, and gerrymandering provides a clear example of how political processes change across scales. The effects of boundary manipulation vary based on the level at which districts operate:

Local scale: School boards, municipal councils, and city districts may experience changes that directly impact neighborhood-level representation and resource allocation.

State scale: State legislative districts influence intrastate political power, budget decisions, and policy.

National scale: Congressional gerrymandering shapes the composition of national legislatures, affecting federal policymaking and political balance.

Understanding these scale relationships is essential for analyzing how boundary design influences both the allocation of power and broader national electoral patterns.

Geographic, Legal, and Technological Contexts

Gerrymandering is shaped not only by political intent but also by broader geographic and institutional forces.

Key contextual factors include:

Legal frameworks: Courts may restrict certain practices, such as racial gerrymandering, but allow others, like partisan gerrymandering in some jurisdictions.

Technological advances: Mapping software and demographic data allow for increasingly precise boundary manipulation.

Population distribution: Urban-rural divides and demographic clustering influence the opportunities available to gerrymander effectively.

Political decentralization or centralization: States with highly centralized redistricting control may see stronger partisan influence.

These elements show how gerrymandering is embedded within the broader political-geographic system and how spatial technologies and demographic patterns shape political outcomes.

Broader Political Consequences

The design of electoral boundaries can produce far-reaching political effects, reinforcing the syllabus focus on how boundary manipulation changes election outcomes.

Consequences include:

Shifting policy priorities as parties with manufactured majorities gain legislative control.

Increased polarization caused by uncompetitive districts that reward ideological extremity.

Challenges to democratic legitimacy, as manipulated boundaries reduce public trust in electoral fairness.

Long-term entrenchment of power structures even when voter preferences change.

FAQ

Gerrymandering involves deliberately redrawing district boundaries to engineer political advantage, while malapportionment refers to districts having unequal populations due to outdated or improper redistribution.

The distinction matters because gerrymandering is an intentional manipulation of spatial patterns, whereas malapportionment is often a result of demographic change or failed redistricting.

Gerrymandering reshapes political geography through strategic boundary design, whereas malapportionment undermines representation by violating the principle of equal population across districts.

Legal constraints vary widely and can shape how much control political actors have over boundary drawing.

Common limiting factors include:

• independent redistricting commissions

• constitutional population equality requirements

• judicial scrutiny of discriminatory districting

• public transparency rules during map-making

These mechanisms reduce direct partisan influence and increase oversight, making it harder for political actors to manipulate districts freely.

Certain groups tend to be geographically clustered, making them easier to pack or crack.

Groups disproportionately affected include:

• ethnic minorities concentrated in urban areas

• younger voters in university towns

• low-income populations in dense housing areas

Geographic clustering allows map designers to target these groups more effectively, amplifying or weakening their collective political voice.

Digital mapping tools offer unprecedented precision in predicting political outcomes at the level of individual streets or neighbourhoods.

These technologies allow political actors to:

• model voting behaviour using extensive demographic datasets

• simulate thousands of map outcomes to find the most advantageous design

• evaluate the impact of boundary adjustments before finalising a district

This data-driven approach has made contemporary gerrymandering more targeted and durable.

Early signs often appear before election results are available.

Indicators include:

• unusually irregular or elongated district shapes

• communities of interest being split despite geographic continuity

• extreme election predictions compared with past voting patterns

• disproportionately safe seats emerging across a state

These clues suggest intentional boundary manipulation designed to entrench political advantage.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how cracking operates as a method of gerrymandering.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for stating that cracking involves dividing a concentrated group of voters across multiple districts.

• 1 mark for explaining that this reduces the group’s ability to influence election outcomes.

• 1 mark for linking cracking to the broader aim of weakening an opposition party or group.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of political geography, analyse how gerrymandering can influence representation at different spatial scales.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying that gerrymandering alters electoral district boundaries to favour certain parties or groups.

• 1 mark for describing effects at the local scale (e.g., neighbourhood representation, school board elections).

• 1 mark for describing effects at the state scale (e.g., legislative seat distribution, policy direction).

• 1 mark for describing effects at the national scale (e.g., composition of the national legislature, national policy outcomes).

• 1 mark for explaining how these scale-based effects shape political power or voter influence.

• 1 mark for showing clear analytical understanding of how altered district boundaries redistribute political advantage across scales.