AP Syllabus focus:

‘The rank-size rule helps explain patterns in city sizes within a country by comparing the largest city to progressively smaller cities.’

The rank-size rule provides a geographical framework for understanding how cities relate in size, revealing expected proportional patterns that help explain national urban organization and spatial hierarchy.

Rank-Size Rule: Expected City-Size Patterns

The rank-size rule is a foundational concept in urban geography used to examine the distribution of city sizes within a country. It asserts that there is a predictable relationship between a city’s rank in the national urban hierarchy and its population size, offering insight into how evenly or unevenly population and functions are distributed across a system of cities. This framework helps geographers analyze whether a country’s urban landscape is balanced, diversified, or dominated by one or a few major cities. The AP specification emphasizes that the rank-size rule “helps explain patterns in city sizes within a country by comparing the largest city to progressively smaller cities,” making it central to understanding expected urban-size relationships.

Core Concept of the Rank-Size Rule

The rank-size rule suggests that a city’s population is inversely proportional to its rank.

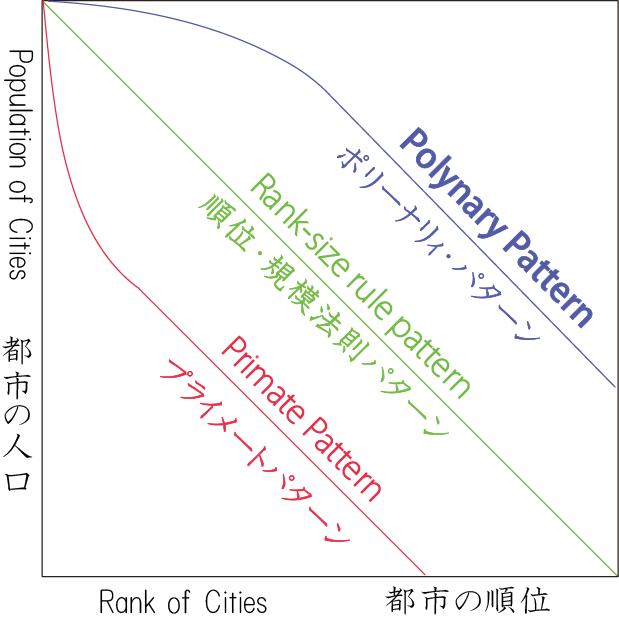

A log–log graph showing the relationship between city rank and population, illustrating how population decreases predictably with increasing rank. This visual reinforces the expected proportional pattern described by the rank-size rule. The image focuses solely on rank and population without introducing content beyond this subtopic. Source.

In an idealized version of this system, the second-largest city is expected to have half the population of the largest, the third-largest would have one-third, and so on. This relationship highlights the internal structure of urban systems and whether they display a balanced hierarchy, a dominant primate city, or an uneven distribution of population.

Rank-Size Rule: A geographic pattern in which a city’s population is inversely proportional to its rank in the urban hierarchy.

When the rank-size rule holds true, it often signals that a country has a well-integrated economy, with multiple cities providing significant services, economic functions, and regional connectivity.

Mathematical Expression of the Rule

Urban geographers frequently express the rank-size rule using a simple formula that relates rank and population. While the rule is conceptual, its mathematical form enables clearer comparisons across countries and time.

\text{Population of a City (P_r)} = \frac{P_1}{r}

= Population of the largest city

= Rank of the city within the national hierarchy

This equation does not claim perfect accuracy but serves as a benchmark for identifying whether cities deviate significantly from expected patterns.

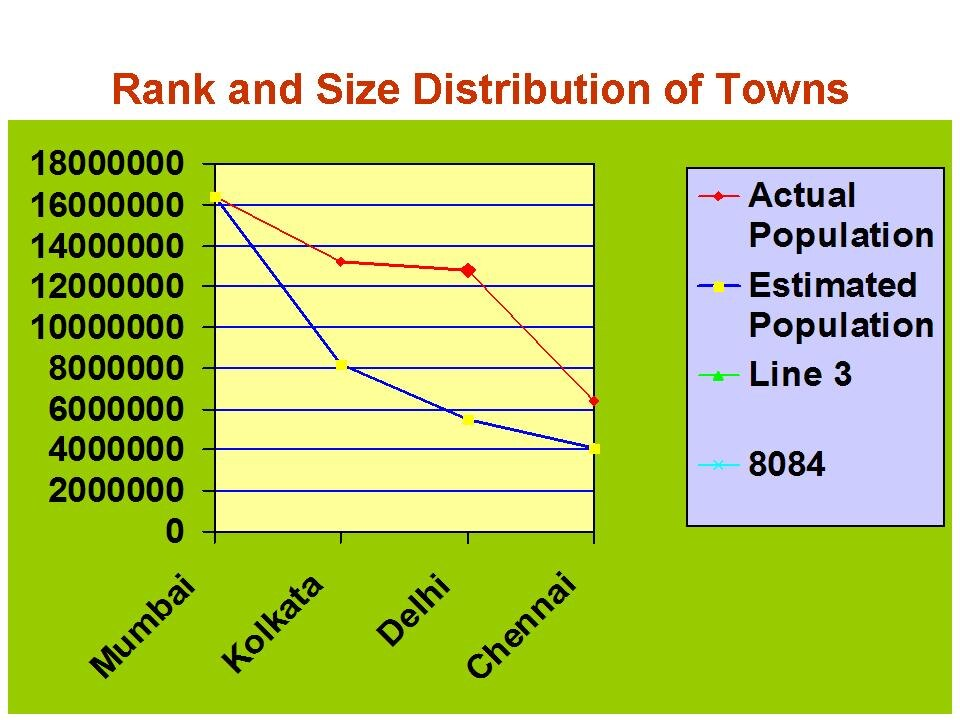

A graph displaying the ranked populations of towns in India, forming a pattern consistent with the rank-size rule. It visually demonstrates how real-world urban systems may approximate the expected relationship between rank and population. The figure contains many towns, but all information remains focused on rank and population distribution. Source.

A system closely matching this equation is said to exhibit urban regularity, while strong deviations often indicate different developmental, historical, or political influences.

Conditions That Support Rank-Size Distribution

Several conditions tend to support whether a country’s cities follow the rank-size rule. These conditions help explain why some nations display balanced city-size patterns while others diverge due to unique socioeconomic trajectories.

Historical and Economic Conditions

Countries with long-standing, well-distributed networks of trade and transportation often exhibit rank-size distributions. Over time, economic diversification spreads across multiple urban centers rather than concentrating exclusively in one city.

Political Influences

Government policies that promote regional equity, infrastructure distribution, and decentralization tend to produce rank-size patterns. When investment is evenly distributed, multiple cities grow in tandem.

Demographic Trends

Sustained patterns of internal migration, especially rural-to-urban flows into multiple regions, can reinforce proportional growth across cities rather than funneling migrants into a single dominant metropolis.

What the Rank-Size Rule Reveals About National Urban Systems

Geographers use the rank-size rule because it illuminates several aspects of city organization and spatial structure.

Economic Integration

Balanced city sizes often indicate robust intercity connectivity in trade, labor, and services.

Multiple competitive urban centers help reduce overdependence on a single dominant core.

Distribution of Services and Opportunities

When the rule holds, high-order services (e.g., finance, research) are more likely to be distributed across several large cities.

Residents gain broader access to employment, education, and cultural amenities.

Spatial Hierarchy and Urban Balance

A close match to the rule shows a tiered urban hierarchy where settlement sizes decrease gradually rather than abruptly.

This contrasts sharply with primate-city systems, where one city disproportionately dominates.

Deviations From the Rank-Size Rule

Few countries fit the rank-size rule perfectly; deviations are important to understanding national development patterns.

Primate City Deviations

In countries with a primate city, the largest city is disproportionately large compared to all others, violating rank-size expectations. This indicates centralized political power, colonial histories, or uneven economic investment.

Emerging and Rapidly Urbanizing Countries

Nations undergoing rapid urbanization may show irregular city-size distributions as growth occurs faster than infrastructure and investment can spread. Over time, some of these countries may move closer to rank-size patterns as their economies mature.

Advantages of Rank-Size Urban Systems

Urban systems that approximate the rank-size rule often experience several key benefits.

Reduced Urban Strain

Multiple large cities help distribute population pressures, lowering congestion and infrastructure overload in the largest city.

Economic Resilience

Diverse urban centers strengthen national economic stability, reducing vulnerability to downturns concentrated in a single metropolis.

Improved Regional Equity

More balanced city sizes support equitable access to jobs, services, transportation, and political power.

FAQ

Geographers usually examine population data for all major cities and plot city size against rank to observe the overall pattern. A straight or near-linear decline in population suggests a strong fit.

They also compare results across different years to see whether the pattern stabilises or shifts over time.

In some cases, geographers calculate statistical correlation values to measure how closely a country approximates a rank–size distribution.

Highly developed countries often have long-established transport networks, strong regional economies, and decentralised investment that support growth in multiple major cities.

These countries may also have:

• balanced migration flows

• diversified industrial and service bases

• strong governance structures that distribute resources more evenly

Such characteristics reduce the likelihood of a single dominant primate city emerging.

The rule becomes less meaningful when applied to countries with only a handful of major settlements. With too few cities, deviations may appear artificially large even when development is balanced.

However, geographers may still use the rule as a descriptive tool to highlight whether one settlement disproportionately dominates the urban hierarchy.

Historical patterns of colonisation, industrialisation, and state formation strongly affect urban size patterns.

For example:

• Colonial powers often concentrated infrastructure and administration in a single city, disrupting rank–size expectations.

• Countries that industrialised early tend to have multiple cities growing simultaneously, making a rank–size pattern more likely.

• Civil conflict or long-term political instability can cause temporary or permanent deviations.

Yes. This can occur when national development becomes more regionally balanced, allowing secondary cities to expand.

Shifts typically result from:

• major investment in regional transport or industry

• decentralisation of government institutions

• targeted policies encouraging population and economic growth outside the dominant city

Such transitions generally occur over decades rather than years, as secondary cities gradually gain economic and demographic weight.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain what the rank–size rule shows about the expected relationship between a city’s population size and its rank within a country’s urban hierarchy.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for stating that cities decrease in size as rank increases.

• 1 mark for describing that the second-largest city is expected to be about half the size of the largest, the third about one-third, etc.

• 1 mark for noting that the rule indicates a balanced or regular distribution of city sizes within a national urban system.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of urban geography, explain two ways in which a country might deviate from the rank–size rule and discuss what these deviations reveal about national development patterns.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a primate city as a deviation from the rank–size rule.

• 1 mark for explaining that primacy indicates concentration of population, power, or investment in one major city.

• 1 mark for identifying irregular or uneven city-size distributions in rapidly urbanising countries as another deviation.

• 1 mark for explaining that such irregularity may reflect economic imbalance, colonial history, or uneven regional development.

• 1–2 additional marks for clear discussion of what these deviations reveal about broader national patterns (e.g., political centralisation, lack of integrated infrastructure networks, uneven economic opportunities).