AP Syllabus focus:

‘These urban principles can be used to explain and predict the distribution, size, and interaction of cities across regions and countries.’

Geographers apply classic urban models to interpret how cities grow, interact, and organize space, using theories to understand real-world patterns of settlement size, spacing, function, and connectivity.

Applying Urban Models to Real-World City Patterns

Urban models offer structured ways to interpret the complex distribution and behavior of cities. By applying urban hierarchy, the rank-size rule, primate city dynamics, the gravity model, and central place theory, geographers can identify predictable patterns of size, spacing, and interaction across regions. These models help reveal why some cities dominate national systems, why others specialize, and how flows of people, goods, and services link urban areas into functional networks. While no single model fits every context, each illuminates important principles of urban structure and spatial relationships.

Using Urban Hierarchy to Explain City Roles

Urban hierarchy refers to the organization of settlements based on their size, functions, and service provision. Larger cities typically offer more specialized and high-order services, while smaller towns provide basic, low-order needs. This framework allows geographers to understand:

How cities occupy different levels within a regional system

Why higher-order cities attract larger market areas

How economic specialization increases as city size increases

The hierarchy clarifies how settlements depend on one another and highlights interconnections that structure regional urban networks.

Applying the Rank-Size Rule to City-Size Distributions

The rank-size rule predicts that the population of a city is inversely proportional to its rank within the national urban system. When countries follow this regular pattern, their urban systems tend to be functionally balanced, with multiple large cities distributing services and economic activity.

= Size of the top-ranked city

= Position of a city in the national hierarchy

This equation enables geographers to measure whether a country’s settlement pattern shows proportional distribution or diverges toward primacy. A close match to the model often signals diversified economic geography, strong regional cities, and widespread connectivity.

Identifying Patterns of Primate City Dominance

A primate city is a settlement that is more than twice as large as the next-largest city and dominates national cultural, political, and economic life.

Primate City: A city that is disproportionately large and influential compared to others in the national hierarchy.

Understanding primacy helps explain uneven development, internal migration flows, and the concentration of investment in a single urban center. Applying this concept reveals how political centralization, colonial histories, or economic forces create imbalanced urban systems.

Between these models, geographers can differentiate systems that are evenly distributed from those skewed toward one dominant urban core.

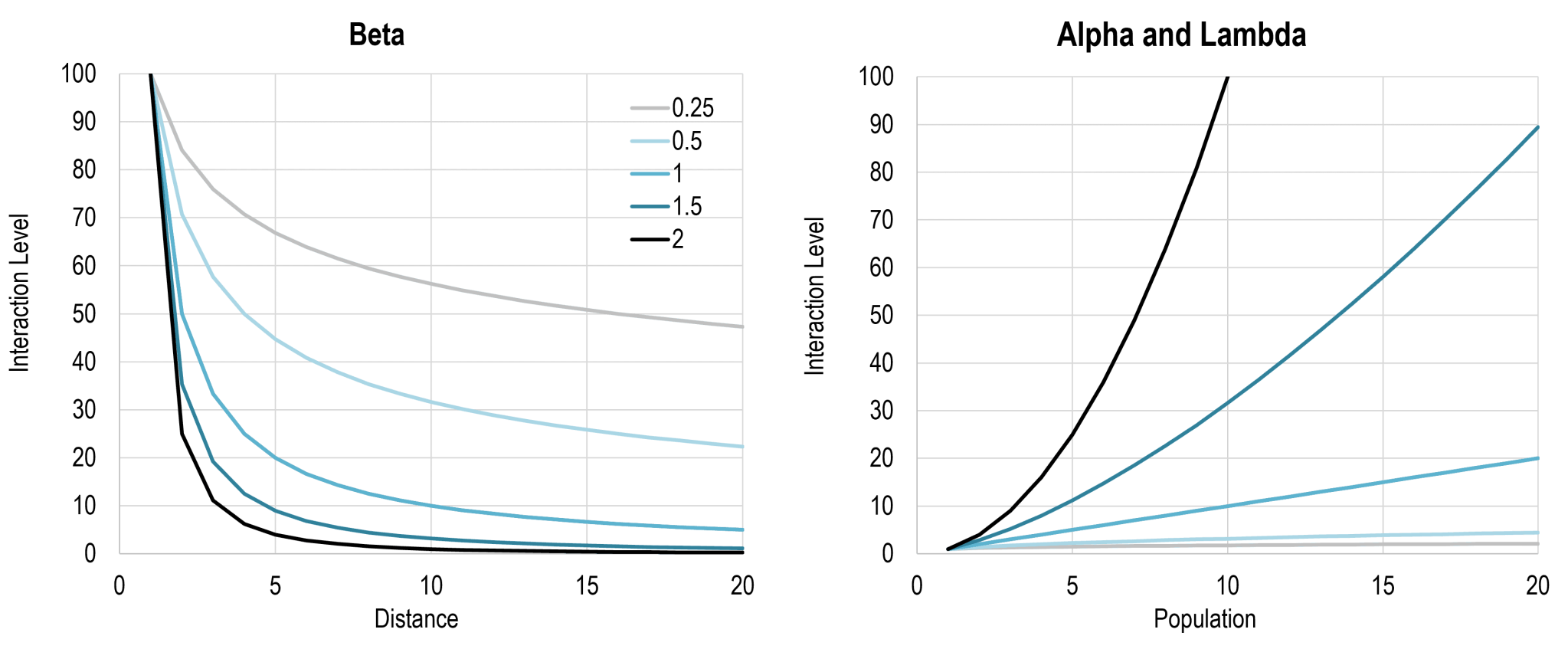

Predicting City Interaction with the Gravity Model

The gravity model estimates the level of interaction between two cities based on their population sizes and distance. Larger and closer cities interact more intensely through commuting, trade, communication, and migration. The model helps explain:

Why major metropolitan pairs (e.g., nearby regional hubs) form strong corridors

How transportation improvements increase interaction

Why distant or smaller settlements maintain weaker connections

Through its mathematical approach, the model provides a predictive tool for understanding flows linking cities within regional and national systems.

This diagram illustrates spatial interaction through the gravity model, showing how flows between cities increase with population (mass) and decrease with distance. It visually reinforces the concept that larger and closer urban areas experience stronger interactions. Some additional parameters appear, but they still support the model’s core AP-relevant principles. Source.

After applying the gravity model, geographers can compare predicted interactions with observed patterns to identify anomalies caused by political boundaries, cultural ties, or infrastructure constraints.

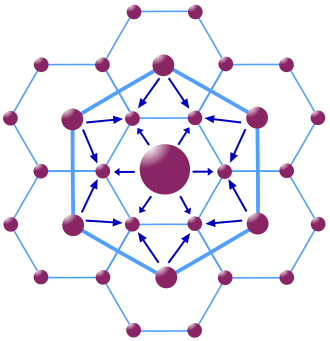

Interpreting Settlement Spacing with Central Place Theory

Central place theory uses ideas of range and threshold to explain settlement spacing and the distribution of services.

Range: The maximum distance consumers are willing to travel to access a service.

Threshold: The minimum population required to support a service.

The model illustrates how cities and towns emerge in a hexagonal pattern of service areas, minimizing overlap and ensuring efficient access.

This graphic shows Christaller’s hexagonal market-area system, with higher-order centers surrounded by progressively lower-order centers. The hexagonal tiling demonstrates how services can be efficiently arranged without gaps. The diagram includes extra geometric detailing, but all elements reinforce the model’s essential concepts. Source.

One normal sentence is required before presenting additional structured information, ensuring conceptual clarity as students examine how theoretical spacing contrasts with real geographic landscapes.

Integrating Models to Understand Real-World Urban Systems

When applied together, these models provide a multifaceted perspective on city patterns:

Urban hierarchy frames settlement relationships.

Rank-size rule measures proportionality.

Primate city analysis identifies dominance or imbalance.

Gravity model predicts flows and interactions.

Central place theory explains spacing and service distribution.

Geographers use these principles to analyze regional urbanization, anticipate growth, and interpret the alignment—or misalignment—between theoretical models and actual city systems across the world.

FAQ

Geographers choose models based on the characteristics of the region, the quality of available data, and the scale of analysis. Regions with strong infrastructural networks may fit interaction-based models, while areas with evenly spaced settlements may align more closely with central place theory.

They also consider historical context, political structure, and economic organisation to match model assumptions with real conditions. No model is universally applicable, so geographers often compare multiple models before selecting the most suitable one.

Several dynamic processes can cause this shift:

Concentration of political power in a single capital

Rapid industrialisation in one urban centre

Colonial legacies that channelled investment into one port or administrative hub

As one city becomes disproportionately important, migration, infrastructure development, and economic opportunity become increasingly centralised, reinforcing primacy.

Natural landscapes create barriers that distort theoretical spacing. Mountains, rivers, coasts, and climate conditions influence where settlements can develop.

Human factors also disrupt ideal patterns, including transport corridors, planning decisions, and historical settlement origins. Because of these variables, actual settlement patterns reflect an interplay of accessibility, opportunity, and constraint rather than a pure geometric layout.

They compare predicted interaction levels with real-world data such as commuting flows, trade volumes, transport usage, and communication patterns.

If discrepancies arise, geographers check for additional influences not captured by the model, including cultural ties, political boundaries, or infrastructural bottlenecks. Adjustments to distance decay or population weighting may be made to improve accuracy in future analyses.

Each model highlights different spatial relationships. Applying more than one helps geographers capture complexity in city systems.

For example:

Central place theory explains spacing and service areas.

The gravity model clarifies interactions and movement flows.

Rank–size considerations reveal balance or imbalance in city size distribution.

Combined, these perspectives allow for more nuanced interpretations of how cities develop, compete, and function within wider regional networks.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how the rank–size rule can help geographers identify whether a country’s urban system is evenly distributed or dominated by a primate city.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

• 1 mark for stating that the rank–size rule predicts a proportional relationship between a city’s population and its rank in the urban hierarchy.

• 1 mark for explaining that close alignment with the rule indicates a more balanced and evenly distributed urban system.

• 1 mark for explaining that significant deviation from the rule (e.g., one city much larger than expected) suggests primacy or disproportionate dominance.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using two urban models, analyse how geographers apply theoretical principles to interpret real-world patterns in the size, spacing, or interaction of cities.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

• 1 mark for identifying a valid urban model (e.g., central place theory, gravity model, rank–size rule, primate city concept, urban hierarchy).

• 1 mark for identifying a second valid and distinct model.

• 1 mark for explaining how one model is used to interpret real-world city size or spacing (e.g., hexagonal market areas, thresholds, or range in central place theory; proportional size distribution in the rank–size rule).

• 1 mark for explaining how the second model is applied to real-world interaction or distribution (e.g., predicting flows using population and distance in the gravity model; identifying dominance through primate city analysis).

• 1 mark for making a clear analytical link between model predictions and observed urban patterns.

• 1 mark for demonstrating depth, such as noting limitations, variation across regions, or why models may not perfectly match actual city systems.