AP Syllabus focus:

‘A primate city dominates a country’s urban system, often concentrating population, power, and economic activity in one major city.’

Urban primacy reflects extreme concentration of people and functions in a single dominant city, shaping national development, spatial balance, governance, and economic and cultural opportunities across a country.

Primate Cities: Causes and Regional Impacts

Understanding Primate Cities

A primate city is a city that is disproportionately large and influential compared to all others in a country. It is typically more than twice the size of the next-largest city and holds outsized political, economic, and cultural power. This dominance creates spatial patterns distinct from countries that follow the rank-size rule.

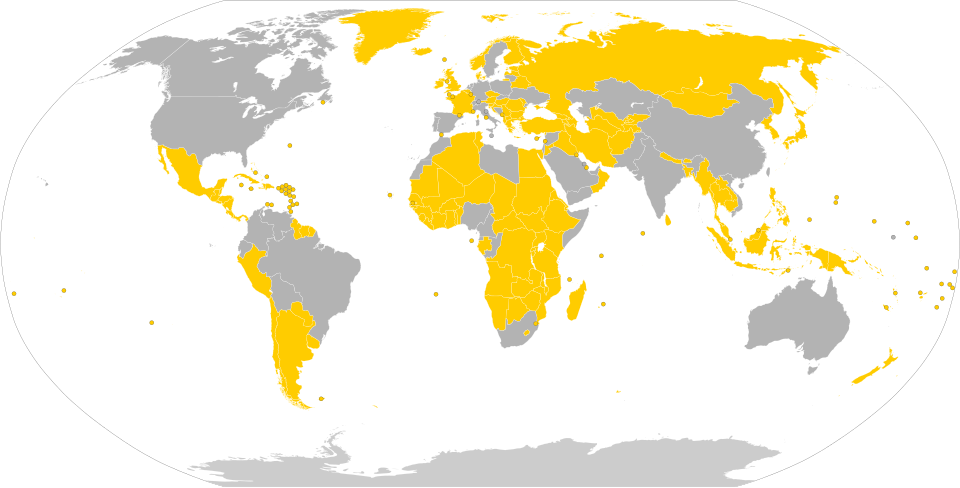

World map showing countries that have a primate city highlighted in yellow. This illustrates the global distribution of urban primacy across multiple world regions. The map includes only the presence of primate cities and excludes additional demographic or economic details. Source.

Primate City: A city that is more than twice the size of the country’s next-largest city and exerts dominance over political, economic, and cultural systems.

Primate cities develop through a combination of historical, political, and economic processes that reinforce their geographic centrality and national importance. Their emergence is rarely accidental; instead, it reflects long-term institutional and infrastructural choices that favor one urban center over others.

Causes of Primate City Development

Historical and Colonial Legacies

Many primate cities originated during colonial eras, when colonial powers concentrated administrative functions, trade infrastructure, and investment in one strategic urban center. This pattern often persisted after independence.

Key processes include:

Centralized colonial administration that created a single political and bureaucratic core.

Port cities favored for extraction and export, fostering early economic dominance.

Limited investment in interior or secondary cities, reinforcing spatial inequality.

Political Centralization

Highly centralized governments often channel national resources through one primary city, strengthening its dominance.

Drivers include:

Concentration of government ministries, national legislatures, and decision-making centers.

Preferential allocation of infrastructure spending, such as major transportation corridors radiating from the primate city.

Attraction of elite labor, embassies, and international organizations seeking proximity to decision-makers.

This political focus creates a feedback loop: the primate city attracts more institutions, which in turn strengthens its primacy.

Economic Forces and Agglomeration

Primate cities frequently benefit from agglomeration economies, the efficiencies gained when firms cluster together.

Agglomeration Economies: Cost advantages and productivity benefits that occur when related industries cluster in the same location.

Agglomeration leads firms, skilled workers, and consumers to concentrate in the primate city, further expanding its economic pull.

Contributing economic forces include:

Large consumer markets encouraging the location of national headquarters, media, and services.

Transportation hubs offering access to global trade and travel networks.

Early industrialization that took place in the primate city first, anchoring long-term urban primacy.

Regional Impacts of Primate Cities

Primate cities shape national development patterns profoundly, producing benefits and challenges that extend far beyond their boundaries.

Positive Regional Impacts

Primate cities can function as engines of growth with substantial national benefits.

Key positive impacts:

Economic dynamism driven by large labor markets and diverse industries.

Cultural influence through universities, media, and creative industries that strengthen national identity.

Efficient concentration of services, including finance, health care, and advanced business functions.

Global connectivity, enabling the country to insert itself into international trade, tourism, and investment flows.

These advantages can elevate national competitiveness and modernization.

Negative Regional Impacts

Despite their benefits, primate cities often deepen geographic inequalities and stress national infrastructure.

Major challenges include:

Overurbanization, where population growth outpaces housing, transportation, and service capacity.

Rural and secondary-city underdevelopment, as capital and labor drain toward the primate city.

Spatial imbalance, producing uneven economic landscapes and limited diversification outside the core region.

Congestion, pollution, and social inequality due to extreme concentration of population.

Vulnerability to political and economic shocks, because so much activity depends on a single city.

These disadvantages highlight the risks of excessive urban concentration.

Primate Cities and Urban Systems

Primate cities contrast sharply with urban systems that follow the rank-size rule, in which cities decrease in size predictably down the urban hierarchy.

In primate-city countries, the urban hierarchy is steep and uneven, creating a dominant core surrounded by much smaller secondary centers.

Urban System: The network of cities within a country and the relationships among them based on size, function, and connectivity.

In primate-city countries, the urban hierarchy is steep and uneven, creating a dominant core surrounded by much smaller secondary centers. This structure shapes national migration patterns, as people often move internally toward the primate city for employment and education.

Broader Geographic Significance

Primate cities influence transportation patterns, regional planning, and spatial decision-making at the national scale. Their dominance affects how roads, railways, and communication systems are built, often reinforcing the city’s centrality. They also shape demographic patterns by concentrating young, skilled populations in the core, while peripheral regions experience slower growth or decline.

Primate cities remain important case studies in AP Human Geography because they reveal the interaction between urban form, political power, economic forces, and geographic inequality across national space.

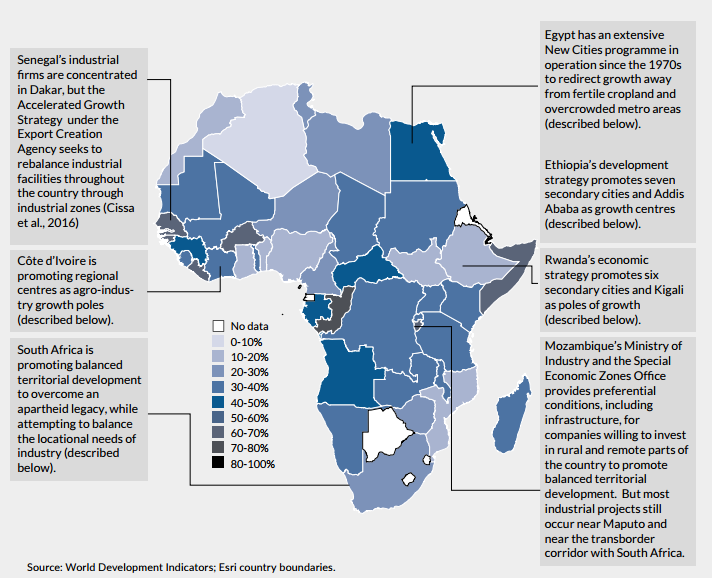

Choropleth map of Africa displaying the share of each country’s urban population residing in the largest city, with darker tones indicating stronger primacy. Surrounding callout boxes summarize various national strategies to strengthen secondary cities and reduce spatial imbalances. The policy examples exceed AP syllabus depth but clearly illustrate real-world responses to primate city dominance. Source.

FAQ

A primate city is defined by its disproportionate size and influence, whereas a capital city is defined by its political function. They may overlap, but they are not inherently the same.

A country can have a capital that is not a primate city, such as in nations where development is more evenly distributed. Similarly, a primate city does not need to be the capital if another city holds governmental functions while the primate city dominates economically or culturally.

Primate cities tend to accumulate cultural institutions because they attract large populations, diverse communities, and investment.

They frequently host:

• national museums and theatres

• creative industries

• major media outlets

• flagship universities

This concentration reinforces the city’s symbolic status and shapes national identity, often making cultural production uneven across a country.

Internal migration flows often move from rural regions and smaller cities toward the primate city.

This usually occurs because of:

• perceived job opportunities

• higher education availability

• better access to health and services

• strong transport links

These flows further enlarge the primate city while depopulating or stagnating surrounding regions, deepening spatial imbalance.

Primate cities often require governance structures that exceed typical municipal capacities. Their population size and economic importance create administrative complexities.

Key challenges include:

• coordinating infrastructure across vast metropolitan areas

• balancing national and local interests

• managing rapid resource demand

• handling migration pressures

Their dominance can also create tensions with other regions that feel neglected by central decision-making.

Governments sometimes attempt to reduce urban primacy to promote balanced development.

Typical strategies include:

• investing in secondary cities

• relocating government ministries or agencies

• improving regional transport networks

• establishing special economic zones outside the primate city

These policies aim to redirect people, investment, and functions to other urban areas, though success varies based on political will and economic stability.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why a primate city may develop within a country’s urban system.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid reason for primate city development (e.g., political centralisation, colonial history, economic agglomeration).

1 mark for describing how this factor contributes to the growth of a single dominant city.

1 mark for further elaboration showing clear geographic understanding (e.g., concentrated investment, infrastructure radiating from the capital, clustering of skilled labour).

Maximum: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using an example of a primate city, analyse two regional impacts it has on the country. Your answer should refer to both positive and negative effects.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for each well-developed impact (maximum 6 marks).

To earn full marks, answers must include one positive and one negative impact.

For each impact:

1 mark for identifying a relevant impact (e.g., economic dominance, overurbanisation, cultural influence, regional inequality).

1 mark for explaining how the primate city produces this impact.

1 mark for using an appropriate example or specific detail (e.g., Paris shaping France’s economic hierarchy; Bangkok drawing labour from rural Thailand).

Maximum: 6 marks.