AP Syllabus focus:

‘Industrialization changed class structures by expanding industrial workers and creating new groups of factory owners and managers.’

Industrialization reshaped social hierarchies by creating new economic roles, reorganizing labor systems, and redefining relationships between owners, managers, and workers within rapidly growing industrial societies.

Changing Social Hierarchies in Industrializing Societies

Industrialization transformed preindustrial social systems dominated by agrarian hierarchies, typically composed of landowning elites and rural peasants. As production shifted from farms to factories, these older structures gave way to new divisions based on ownership of industrial capital, access to wages, and control over labor.

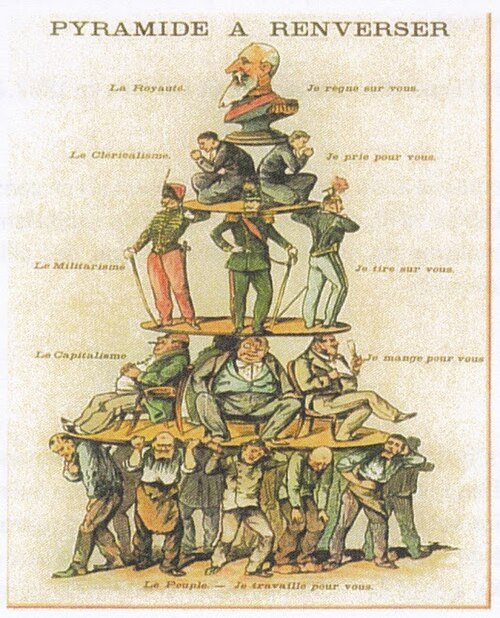

This early-1900s cartoon uses a pyramid to represent a stratified class society, with elites standing on the backs of workers at the base. It visually echoes how industrial capitalism concentrated power and wealth at the top while relying on a broad working class below. The specific figures reflect the Belgian context but still illustrate the general structure of industrial-era class hierarchies. Source.

The Emergence of the Industrial Capitalist Class

Factory Owners and Investors

The industrial capitalist class consisted of individuals who owned factories, machines, and the financial capital used to run them. These owners occupied the top of the new class structure because they controlled the means of production and accumulated profits from industrial output.

Owners invested in machinery, hired laborers, and sought to expand production.

They benefited from increasing demand for manufactured goods in both domestic and global markets.

Their economic power often translated into political influence, particularly in places where voting rights expanded alongside industrialization.

Capitalist Class: The group of individuals who own and control productive industrial assets such as factories, machinery, and investment capital.

Industrial capitalists also shaped urban landscapes by funding mills, mines, and transport infrastructure, reinforcing their central role in industrial society.

The Rise of the Managerial and Professional Middle Class

Supervisors, Engineers, and Clerical Workers

Industrialization generated a managerial middle class, which included supervisors, accountants, engineers, and other salaried professionals needed to coordinate complex factory operations. Their emergence reflected growing organizational needs within large-scale production systems.

Managers oversaw day-to-day work processes and enforced discipline on factory floors.

Engineers developed and maintained new technologies essential for mass production.

Clerical workers handled records and logistics, bridging communication between owners and laborers.

Middle Class (Industrial): A social group of salaried professionals and managers who do not own the means of production but hold higher-status, skill-based positions.

These middle-class roles created more occupational mobility, encouraging formal education and specialized training as pathways to economic advancement.

Expansion of the Industrial Working Class

Factory Laborers and Wage Earners

At the base of the new social hierarchy stood the industrial working class, which grew rapidly as people left rural areas to seek wages in urban factories.

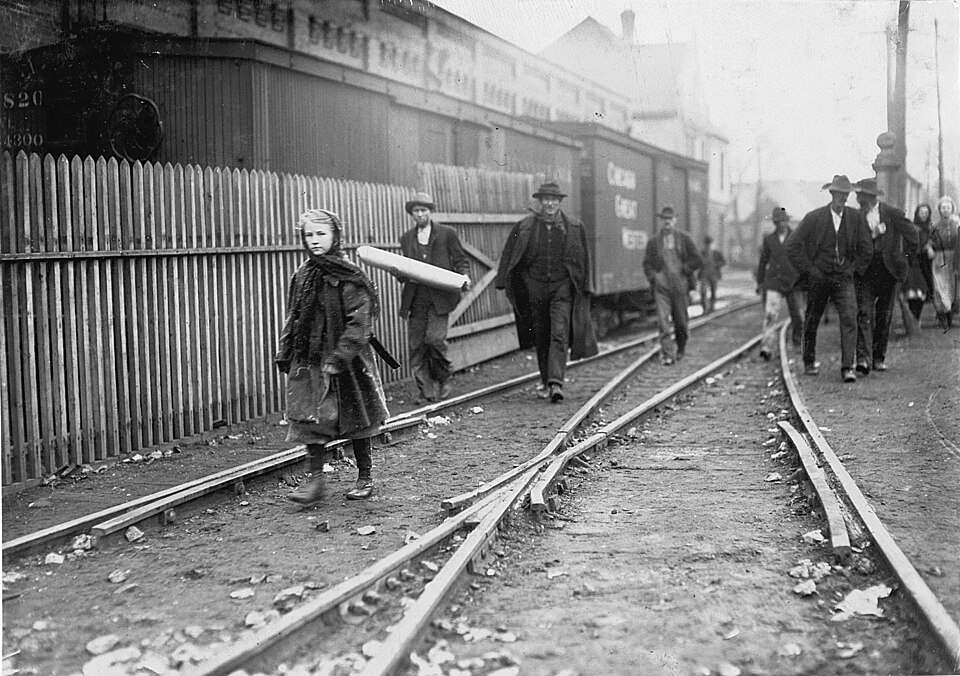

This photograph by Lewis Hine shows workers outside the Brookside Cotton Mill in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1910. Their clothing, ages, and proximity to the factory highlight how industrialization drew entire families into waged labor and concentrated the working class around mills. Child workers provide historical detail beyond the syllabus while illustrating wider inequalities in industrial labor systems. Source.

Workers performed long hours of repetitive tasks in textile mills, steelworks, and other industrial sites.

Wages were often low, and living conditions in overcrowded urban neighborhoods were difficult.

The division between skilled and unskilled labor widened, shaping workers’ economic opportunities.

Working Class (Proletariat): Wage-earning laborers who rely on paid employment in factories or industrial sectors and do not own productive assets.

A sentence to separate definition blocks ensures clarity before introducing new conceptual material.

Industrial workers’ experiences contributed to the growth of labor movements, strikes, and calls for workplace reforms, which eventually influenced legislation on hours, safety, and child labor.

Urbanization and Spatial Class Divisions

Industrialization concentrated populations in cities, where new spatial class patterns emerged. Urban areas often displayed distinct divisions between working-class districts and wealthier neighborhoods.

Working-class families lived near factories to reduce commute time and cost.

Middle-class groups settled in cleaner, more spacious areas farther from industrial pollution.

Wealthy industrialists frequently moved to suburban or elite residential districts, emphasizing their social distance from laborers.

These spatial divisions shaped access to services, education, transportation, and political engagement.

Class Conflict and Social Reform

Reactions to New Inequalities

As class structures changed, tensions emerged between owners seeking higher profits and workers demanding improved conditions. These tensions fueled broader social debates about inequality, justice, and economic rights.

Labor unions formed to advocate for collective bargaining.

Reform movements pushed for expanded suffrage, public education, and social safety nets.

Governments eventually intervened to regulate labor conditions and reduce some of the harshest effects of industrialization.

Middle-class reformers sometimes supported these movements, motivated by moral concerns, fear of social unrest, or belief in orderly progress.

Global Variations in Industrial Class Structures

Though the general pattern of capitalists, managers, and workers appeared across industrializing countries, specific class structures varied based on local resources, political traditions, and cultural norms.

Britain’s early industrialization produced stark class divides tied to coal and textile industries.

Germany’s industrialization emphasized technical education, strengthening the engineer-led middle class.

The United States saw rapid growth in both working-class immigrants and entrepreneurial capitalists in cities like Chicago and Pittsburgh.

These variations show how industrialization both standardized and diversified social structures across the modern world.

FAQ

Industrialisation created a structured dependency: workers relied on owners for wages, and owners relied on workers to operate machinery and sustain production. This interdependence formalised economic roles but also deepened power imbalances.

Factory owners controlled working hours, discipline, and the pace of production, which changed daily life for workers who previously had more autonomy in agricultural settings.

Over time, this relationship shaped debates around rights, regulation, and the moral responsibility of employers toward labourers.

Class rigidity often depended on pre-industrial social systems. Societies with entrenched elites, such as aristocracies, tended to maintain sharper boundaries between classes even as factories expanded.

In contrast, countries with more fluid social structures or frontier economies allowed greater mobility into middle-class or entrepreneurial roles.

Government policy also mattered. Nations investing early in mass education or technical training enabled more movement into skilled industrial occupations.

Education became a key mechanism for accessing middle-class and technical positions. As factories became more complex, literacy and numeracy grew in importance.

Industrial employers increasingly favoured workers with specialised skills, reinforcing schooling as a pathway to higher status.

Middle-class families invested in education to preserve or advance social position, helping formalise distinctions between manual labourers and professional groups.

Gender significantly shaped one’s role within the industrial class structure. Women in working-class households often worked in textiles or domestic service, contributing wages but receiving lower pay and status.

Middle-class women were expected to focus on domestic roles, reinforcing class identity by separating them from industrial labour.

These differences meant that the experience of class varied not just by income or occupation but by gender norms embedded in industrial society.

Industrial jobs created new routes out of rural poverty by offering regular wages and chances to acquire skills unavailable in agricultural work.

However, mobility was uneven. Many migrants faced hazardous conditions and unstable employment, limiting long-term advancement.

Some individuals entered supervisory or skilled trades after gaining experience, but opportunities depended on literacy, training access, and the structure of local labour markets.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain one way industrialisation contributed to the emergence of a new middle class in industrial societies.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid way industrialisation created middle-class roles (e.g., need for managers, accountants, engineers, supervisors).

1 mark for explaining why industrial production required these new professional or managerial positions (e.g., larger factories needed coordination, technical expertise, or administrative oversight).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how industrialisation reshaped the class structure of nineteenth-century societies. In your answer, refer to changes affecting at least two different social groups.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for describing changes to the industrial working class (e.g., rapid growth in wage labourers, factory employment, urbanisation).

Up to 2 marks for describing changes to the industrial capitalist class or factory owners (e.g., accumulation of capital, increased economic power, influence over production).

Up to 1 mark for explaining changes to the managerial or professional middle class (e.g., growth of supervisors, clerks, engineers).

Maximum 5 marks: credit well-developed examples, clear links to industrialisation, and accurate use of key terms.