AP Syllabus focus:

‘Industrial investors sought more raw materials and new markets, helping fuel colonialism and imperialism.’

Industrial capitalism reshaped global economic relationships by driving nations to secure essential inputs, expand market access, and build empires that supported industrial growth and competitive advantage during the nineteenth century.

Industrial Capitalism as a Global Force

Industrial capitalism emerged as factory-based production expanded and investors pursued profits through increased efficiency, competition, and economic growth. As industrial firms scaled up production, they required steady supplies of raw materials, new places to sell manufactured goods, and greater control over global trade routes. These needs linked industrialization directly to the expansion of European imperial power.

Key Drivers of Industrial Expansion

Several pressures encouraged industrial powers to look beyond their borders:

Growing factories required large, continuous quantities of raw materials.

Advanced transportation encouraged long-distance trade.

Expanding manufacturing output created the need for new consumer markets.

National rivalries incentivized states to secure overseas territories before competitors did.

Investors sought higher profits by accessing cheaper labor and resources abroad.

Raw Materials and the Industrial Economy

Industrial capitalism relied heavily on natural resources that were not always available in industrializing countries. This imbalance created global networks of extraction.

Resource Demands

Factories required essential inputs such as cotton, coal, rubber, metals, and food crops. Industrial powers looked to regions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to meet these needs, reshaping global trade flows.

When discussing raw materials, it is essential to understand commodities, which are goods traded primarily for their raw value rather than for processing at the site of extraction.

Commodity: A raw material or agricultural product that can be bought, sold, and shipped for industrial processing or manufacturing.

The geographic concentration of valuable commodities led industrial nations to develop strong economic and political interests in controlling overseas territories.

Industrial powers often justified direct intervention by claiming they were “modernizing” these regions, though the true motivation centered on securing uninterrupted access to valuable resources. These extraction-focused relationships linked colonies to industrial cores through unequal exchange.

New Markets and Expanding Trade

As industrial output increased, domestic markets became insufficient. Manufacturers needed global consumers to maintain profits.

Why New Markets Were Necessary

Industrial output exceeded what domestic populations could purchase.

Overseas markets allowed firms to sell manufactured goods at higher profit margins.

Colonies provided guaranteed markets because imperial governments restricted or shaped trade to favor the colonizing power.

Manufactured Goods and Colonial Dependence

Industrial production created a flow of inexpensive manufactured goods back to colonies, fostering economic dependence. Colonies often lacked the industry to compete and relied heavily on imported products from core countries.

Economic Dependence: A condition in which a region relies on another for manufactured goods, capital investment, or technological expertise.

This relationship reinforced a global economic system where industrial cores gained wealth while colonies remained suppliers of primary goods.

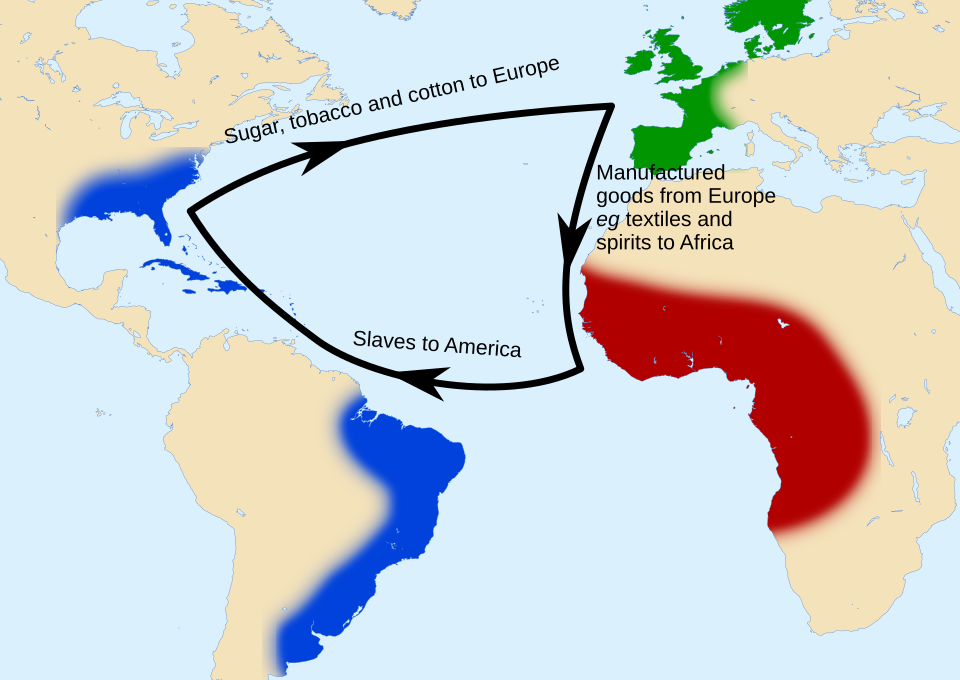

This diagram shows the triangular Atlantic trade linking Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with arrows indicating movements of enslaved people, raw materials, and manufactured goods. Although focused on the earlier slave-based economy, it illustrates how colonies exported primary commodities while the metropolitan core exported finished products. Extra contextual detail related to the slave trade goes beyond this subsubtopic but helps visualize colonial economic dependence. Source.

Industrial Capitalism and the Expansion of Empire

Industrial capitalism played a central role in both colonialism and imperialism, which involved political and economic domination of foreign territories.

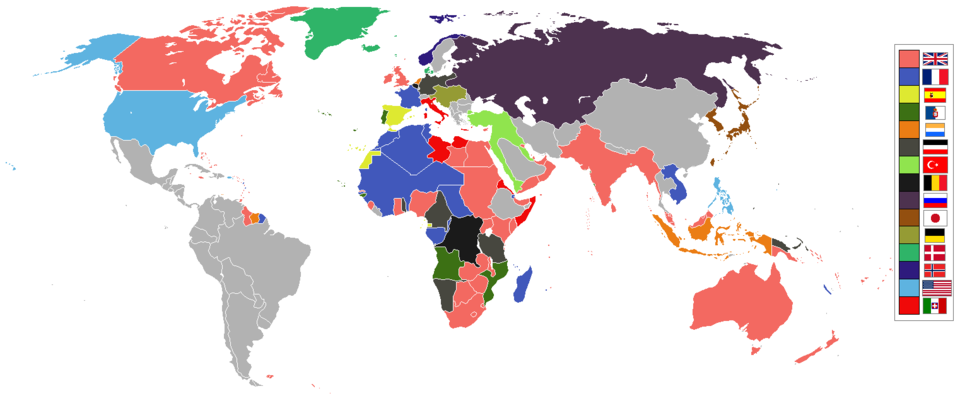

This world map shows major colonial empires and their territories in 1914, illustrating how industrial powers controlled vast regions across Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. It highlights the connection between industrial capitalism and territorial expansion for raw materials and markets. Regions are color-coded to show each empire’s holdings. Source.

Motivations for Imperial Expansion

Industrial nations expanded control overseas for several linked reasons:

Securing raw materials critical for production.

Protecting new investments in transportation and resource extraction.

Establishing naval bases and coaling stations to support global trade.

Preventing rival powers from gaining strategic advantages.

Creating new markets to absorb industrial output.

Forms of Imperial Control

Imperialism varied by region and time period:

Direct rule, such as French West Africa, where colonial governments replaced local political structures.

Indirect rule, notably in British colonies, incorporating local leaders into colonial administration.

Economic imperialism, where foreign companies exerted large influence without formal political takeover, such as the British-controlled opium trade in China.

Each system aimed to ensure industrial investors could access resources and markets with minimal disruption.

Transportation, Infrastructure, and Imperial Networks

Industrial powers invested heavily in transportation systems within colonies to improve resource extraction and trade efficiency.

Infrastructure Used to Support Capitalist Goals

Railways connected interior resource zones with coastal ports.

Telegraph lines facilitated rapid communication between colonies and core nations.

Steamships reduced travel time across oceans, enabling fast delivery of goods.

Canals, such as the Suez Canal, dramatically shortened global shipping routes.

These networks rarely served local populations; instead, they enhanced the ability of industrial cores to control and profit from colonial economies.

Global Consequences of Industrial Capitalism and Empire

Industrial capitalism reshaped the world by deepening global interconnections and widening inequalities between core and peripheral regions.

Major Patterns

Colonies became specialized suppliers of raw materials.

Industrial cores concentrated manufacturing and wealth.

Global trade became structured around unequal economic relationships.

Cultural, social, and political systems in colonized regions were transformed by foreign rule.

Industrial capitalism intensified competition among imperial powers, contributing to international conflicts.

These processes demonstrate how industrialization’s demand for raw materials and markets reshaped global geography and expanded imperial influence, directly reflecting the AP syllabus focus for this subsubtopic.

FAQ

Industrial capitalism shifted demand towards materials that supported mechanised production and mass manufacturing. Colonies that had previously supplied precious metals or small-scale agricultural goods were reorganised to provide bulk commodities such as cotton for textiles, rubber for machinery and transport, and palm oil for industrial lubricants.

This transition often required new plantation systems, forced labour structures, or expanded mining operations, dramatically altering local economies and landscapes.

Industrial powers prioritised regions with accessible high-value resources, favourable climates, and navigable transport routes. Coastal zones with natural harbours and major river systems were especially attractive because they reduced the cost of moving materials to ports.

In areas with difficult terrain or limited infrastructure, colonial governments commonly invested in railways or roads—but only when projected extraction profits justified the expense.

Labour systems were reorganised to maximise extraction efficiency while minimising cost. This produced a range of labour forms, including indentured labour, coerced wage work, and taxation policies that forced local people into colonial economies.

These systems were often racialised and hierarchical, embedding social divisions that persisted well beyond the end of colonial rule.

Chartered companies acted as intermediaries between private investors and imperial governments. They operated with significant autonomy, holding rights to extract resources, build infrastructure, and control local trade.

Their activities frequently preceded formal colonial rule, as seen with the British South Africa Company or the Dutch East India Company, creating economic footholds that later evolved into direct imperial administration.

Colonial cities were structured to support the flow of resources and goods rather than local development. Port districts, railway terminals, and commercial zones were placed at the centre of urban planning, often forming segregated areas controlled by colonisers.

Residential and labour districts for colonised populations typically developed on the periphery, reflecting unequal access to services, political power, and economic opportunity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why industrialising countries in the nineteenth century sought colonies for raw materials.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a basic reason (e.g., factories needed more raw materials).

2 marks: Provides a more detailed explanation linking industrial production to increased demand for specific resources (e.g., cotton, rubber, metals).

3 marks: Clearly explains how limited domestic supplies pushed states to secure overseas territories to guarantee continuous access to essential inputs.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the search for new markets contributed to the expansion of imperial control during the period of industrial capitalism.

Question 2

1–2 marks: Identifies that industrial nations needed new markets to sell manufactured goods.

3–4 marks: Explains how surplus production and competition between industrial powers encouraged expansion into foreign regions.

5–6 marks: Analyses how imperial governments structured colonial economies to ensure guaranteed markets, restrict competition, and integrate colonies into global trade networks; references geographic patterns such as concentrated control in Africa or Asia.