AP Syllabus focus:

‘Congress can limit the Court’s impact through legislation that modifies prior decisions, proposing and ratifying constitutional amendments, and restricting appellate jurisdiction by removing the Court’s authority over certain cases.’

Congress can respond to Supreme Court rulings without overruling cases directly. Its main tools are rewriting statutes, changing the Constitution, and narrowing which cases federal courts—especially the Supreme Court—may hear.

Why Congress Checks the Courts

Judicial review lets courts invalidate laws and executive actions that conflict with the Constitution. Because federal judges have life tenure, Congress’s checks tend to be structural and long-term rather than case-by-case.

These checks aim to:

Reduce a decision’s practical effects

Restore a policy outcome the Court blocked

Prevent the Court from hearing certain categories of disputes

Check 1: Laws That Modify the Effect of Decisions

Congress can often blunt a Court decision by passing a new statute that changes the legal rule the Court was applying.

When legislation works

Legislation is most effective when the Court’s ruling interpreted a federal statute (not the Constitution). Congress may:

Clarify ambiguous wording the Court relied on

Add procedural requirements or enforcement mechanisms

Redefine key statutory terms to change how the law operates

Replace the invalidated provisions with new, constitutionally permissible ones

Key limitation

Congress cannot “override” the Court’s constitutional interpretation with an ordinary law. If the Court said a policy violates the Constitution, Congress must either:

Design a different policy that fits constitutional limits, or

Use the constitutional amendment process

Check 2: Constitutional Amendments

A constitutional amendment can supersede a Supreme Court decision by changing the Constitution itself, altering the standard the Court must apply in future cases.

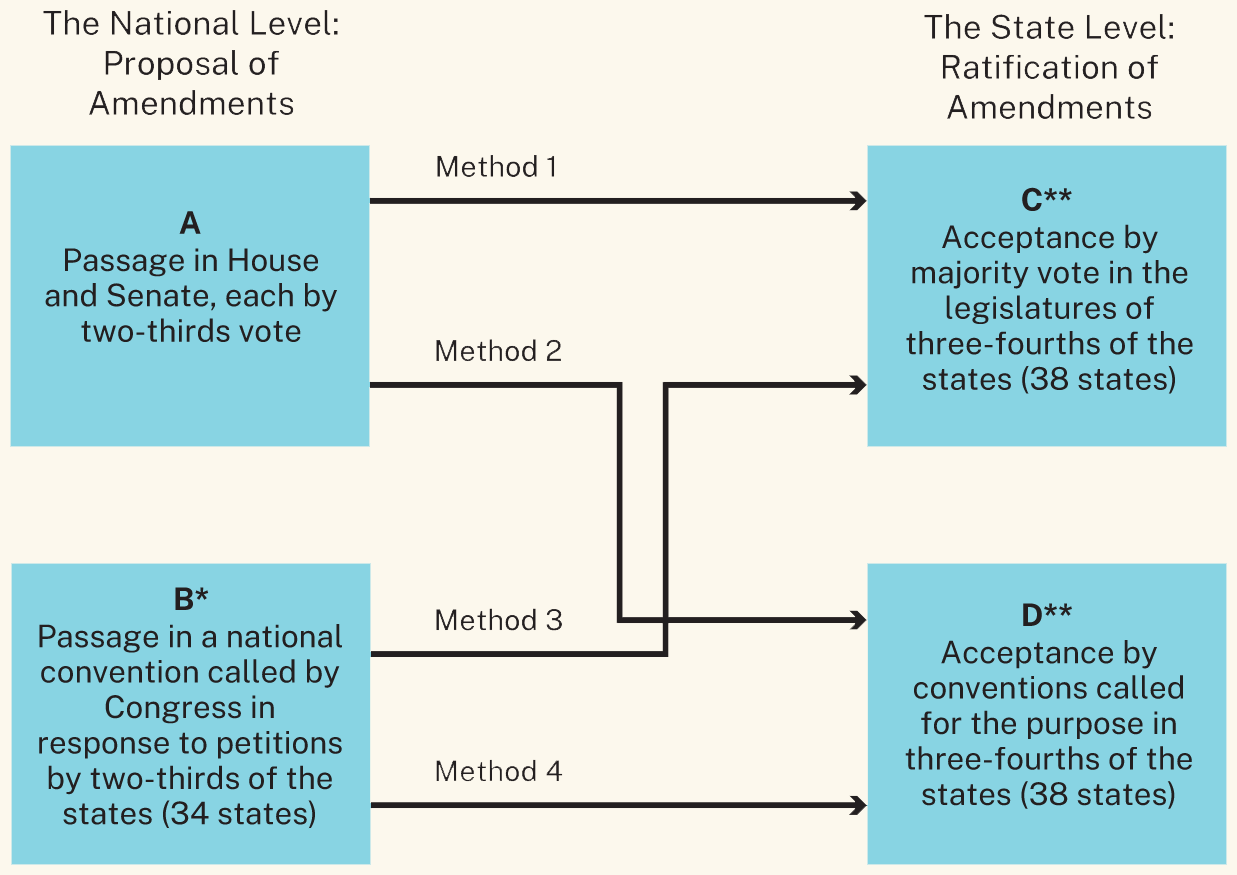

The amendment process is intentionally difficult, requiring broad national agreement:

Proposal (typically) by a two-thirds vote in both chambers of Congress

Ratification by three-fourths of the states

Flowchart of the Article V amendment process showing the two proposal routes (two-thirds of both chambers of Congress, or an Article V convention called by two-thirds of state legislatures) and the two ratification routes (three-fourths of state legislatures, or three-fourths of state ratifying conventions). It visually highlights why amendments are a rare but decisive response to Supreme Court constitutional rulings: the process requires broad, multi-level agreement. Source

Amendments are rare as a response to Court rulings because they require cross-party and cross-state consensus, but they are the strongest congressional check because they change the legal foundation of judicial review.

Check 3: Jurisdiction Limits (Appellate Jurisdiction)

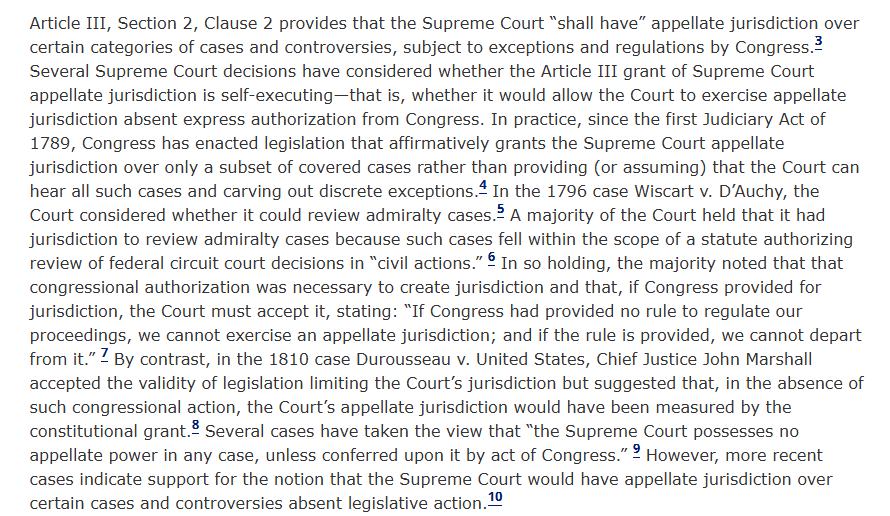

Congress can restrict the Court’s impact by limiting the kinds of cases federal courts may hear—especially through control over appellate jurisdiction.

Excerpted constitutional text of Article III, Section 2, Clause 2 (the Exceptions Clause) distinguishing the Court’s original jurisdiction from its appellate jurisdiction and explicitly authorizing Congress to make “Exceptions” and “Regulations.” This primary-source framing helps students connect jurisdiction-stripping debates to the Constitution’s actual wording and structure. Source

Appellate jurisdiction: A court’s authority to review decisions of lower courts and change, affirm, or reverse those outcomes.

How jurisdiction limits work

Under Article III, Congress has significant power to shape the federal judiciary’s reach. It may:

Make exceptions to the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction in certain subject areas

Route disputes into alternative forums (for example, leaving some matters primarily to state courts)

Structure the lower federal courts (because Congress creates and organizes them)

Why this is a powerful but contested tool

Limiting jurisdiction can prevent the Supreme Court from issuing binding nationwide rulings on targeted issues. However, jurisdiction restrictions raise major debates about:

Access to federal courts for rights claims

Whether limits undermine uniform interpretation of federal law

Separation of powers concerns if Congress appears to be insulating laws from review

Practical Limits on Congressional Checks

Congressional checks are meaningful, but they operate within constitutional boundaries and political realities:

Separation of powers: Congress cannot dictate outcomes in specific cases, and courts retain authority to interpret the Constitution.

Political feasibility: Overriding a decision through legislation requires bipartisan coalition-building (and often presidential agreement), and amendments require overwhelming support.

Policy design constraints: After a constitutional ruling, Congress may need to pursue narrower or differently structured approaches to withstand renewed judicial scrutiny.

FAQ

No. A statute cannot override the Court’s interpretation of the Constitution.

Congress must instead:

change the policy design to fit constitutional limits, or

pursue a constitutional amendment.

It usually refers to Congress removing federal court authority over a defined category of cases, often by limiting the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction.

Debates focus on legitimacy, rights enforcement, and uniformity of federal law.

Not necessarily. Depending on how a law is drafted, review might still occur through:

the Court’s original jurisdiction (narrow), or

alternative litigation pathways in other courts.

The effectiveness depends on statutory design and constitutional constraints.

Because amendments change the constitutional rule itself. Once ratified, they control future judicial interpretation, whereas statutes remain subject to constitutional review and later repeal.

Even when constitutionally possible, Congress may face:

intense party polarisation

veto threats requiring supermajorities to overcome

disagreement over how to rewrite the policy without triggering new constitutional challenges

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks) Describe one way Congress can limit the impact of a Supreme Court decision.

1 mark: Identifies a valid method (new legislation / constitutional amendment / limiting appellate jurisdiction).

1 mark: Accurately describes how the method operates.

1 mark: Applies the description specifically to limiting the Court’s impact (not merely “checks and balances” in general).

(4–6 marks) Explain how congressional jurisdiction limits and constitutional amendments differ as checks on the Supreme Court, and evaluate one strength and one weakness of each

1 mark: Correctly explains jurisdiction limits as restricting what cases the Court may hear (especially appellate jurisdiction).

1 mark: Correctly explains amendments as changing the Constitution and thereby superseding the Court’s interpretation.

1 mark: Strength of jurisdiction limits (e.g., can quickly narrow review in targeted areas if enacted).

1 mark: Weakness of jurisdiction limits (e.g., contested legitimacy/rights access concerns; may not eliminate all judicial review routes).

1 mark: Strength of amendments (e.g., most authoritative/lasting; binds future Courts).

1 mark: Weakness of amendments (e.g., very difficult to pass; requires + support).