AP Syllabus focus:

‘The president and state governments can delay or resist implementing Supreme Court decisions, affecting how quickly and fully court rulings take effect in practice.’

Supreme Court rulings do not enforce themselves.

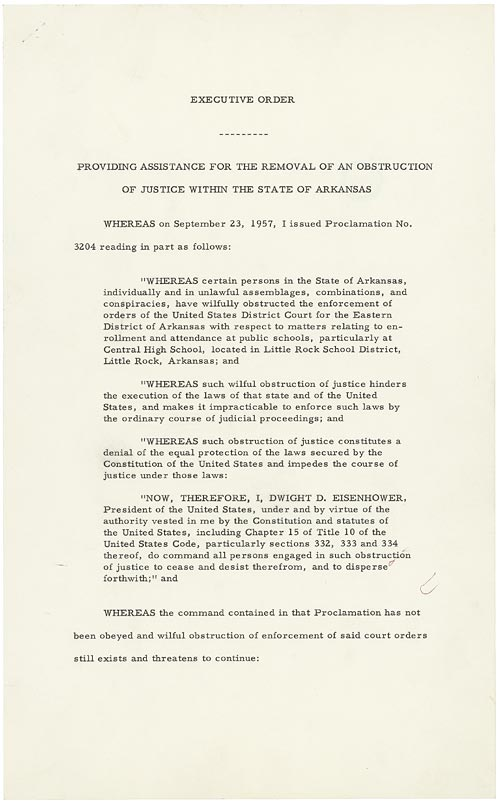

This image shows Executive Order 10730 (1957), issued by President Dwight D. Eisenhower during the Little Rock Crisis. It illustrates how implementation of constitutional rulings can depend on executive action—here, the federal government used its enforcement capacity to carry out federal court orders connected to school desegregation. Source

Implementation depends on cooperation from the executive branch and state governments, which can comply quickly, comply slowly, or resist in ways that shape real-world policy outcomes.

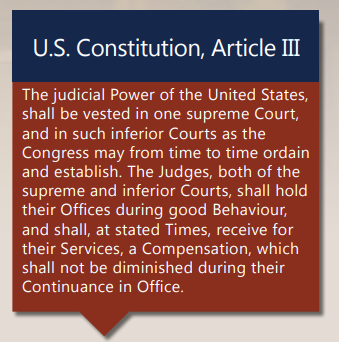

This educational diagram-style page from a U.S. Courts publication summarizes core features of the federal system, including the executive branch’s role in executing/enforcing the laws and the judicial branch’s role in interpreting them. It reinforces the implementation concept by showing that a Supreme Court decision is not self-executing: operational change typically requires action by executive-branch officials and administrators. Source

What “implementation” means after a Supreme Court decision

A Supreme Court decision typically announces a constitutional rule and resolves the parties’ dispute, but practical change requires government actors to carry it out through administration, policing, education, licensing, and elections.

Implementation: The process of putting a court ruling into effect through executive action and state/local administration (e.g., issuing guidance, changing procedures, enforcing new legal standards).

Implementation varies because rulings may be broad, may require new procedures, and often rely on lower courts and officials to interpret details.

Presidential role: enabling, delaying, or narrowing implementation

Tools that can speed up compliance

Presidents can promote implementation when they agree with a ruling or want to avoid legal and political conflict:

Department/agency guidance interpreting the decision for federal programs (e.g., regulations, compliance letters)

DOJ enforcement priorities and litigation strategy (e.g., supporting plaintiffs, seeking injunctions, settling cases)

Federal coordination with states through grants, standards, and technical assistance

Public signalling that compliance is expected, reducing uncertainty for agencies and lower-level officials

Tools that can slow down or limit compliance

Even without openly defying the Court, presidents can affect timing and reach:

Slow rulemaking or limited administrative capacity devoted to enforcement

Narrow legal interpretations that confine a ruling to specific facts

Selective enforcement choices (what cases to bring, what remedies to seek)

Personnel and management decisions that shape agency enthusiasm and follow-through

Because most enforcement is executive-led, presidential priorities influence whether a decision becomes an immediate operational change or a gradual, contested shift.

State role: cooperation, resistance, and “policy feedback”

Why states matter

States administer many systems that court rulings touch—elections, criminal justice, education, public health, and licensing. Even when a case is federal constitutional law, state implementation often determines whether residents experience meaningful change.

Forms of state compliance

Rapid legislative fixes (rewriting statutes to match the constitutional rule)

Administrative updates (training, forms, directives to local officials)

Settlements and consent decrees to standardise compliance across agencies

Forms of resistance and delay

States can resist without formally “nullifying” a ruling:

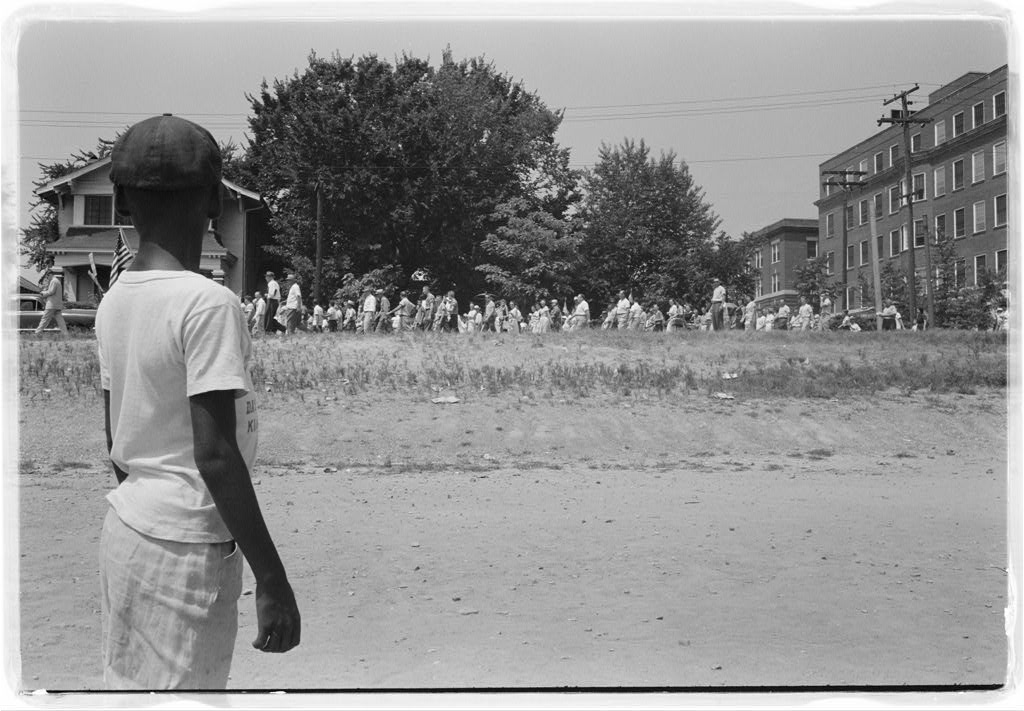

This photograph documents public protest in Little Rock connected to school desegregation, a vivid example of how implementation can be contested on the ground even after constitutional rules are announced. It helps explain why compliance may be uneven across states and localities when officials and the public respond differently to Supreme Court rulings. Source

Narrow compliance: adopting the minimum change needed, leaving related practices intact

Procedural obstacles: new paperwork, deadlines, or jurisdictional rules that reduce access to the right recognised

Repackaging policies: replacing struck-down provisions with functionally similar alternatives designed to survive review

Noncooperation by local officials (sheriffs, clerks, school boards), creating uneven enforcement across counties

Strategic litigation: continuing to defend challenged policies to buy time while cases move through lower courts

Resistance can produce a patchwork in which constitutional rights are applied differently across states until additional lawsuits, federal action, or political change consolidates practice.

Limits on resistance: why defiance is risky but delay is common

Open defiance can trigger:

New lawsuits and federal court orders directing specific steps

Contempt sanctions against officials who violate injunctions

Political backlash and reputational costs for a state

Federal executive pressure tied to funding or enforcement

Delay is more common than outright refusal because it is harder to punish and can be framed as administrative uncertainty or legislative process.

What affects how fast a ruling “takes” in practice

Implementation speed and completeness often depend on:

Clarity of the Court’s opinion (bright-line rule vs. multi-factor test)

Whether lower courts quickly issue remedies (injunctions, monitoring)

Alignment between the ruling and current presidential/state leadership

Administrative capacity (training, data systems, staffing)

Public attention and organised interests pushing compliance or resistance

These dynamics explain why some Supreme Court decisions transform policy quickly while others face prolonged, uneven implementation across the country.

FAQ

In practice, no: federal constitutional interpretations are binding on state officials through the supremacy of federal law.

However, states may still attempt indirect resistance (e.g., narrow compliance or procedural barriers), which must be challenged through further litigation.

A consent decree is a court-approved settlement that can require specific actions and monitoring.

It matters because it can:

lock in timelines and reporting

reduce discretion for future officials

create enforceable obligations beyond general compliance

Many policies are administered locally (e.g., county clerks, school districts, sheriffs).

If local officials refuse to cooperate or interpret rules narrowly, residents may experience unequal access to rights until courts issue targeted orders or state leadership intervenes.

An injunction is a court order stopping (or requiring) specific conduct.

In implementation disputes, injunctions can:

impose immediate compliance deadlines

specify concrete steps agencies must take

expose officials to contempt if they violate the order

Vague standards (multi-factor tests) can produce conflicting interpretations among agencies and lower courts.

That uncertainty encourages:

cautious, minimal compliance

extended litigation over scope

delayed administrative updates while officials wait for clarifying rulings

Practice Questions

Explain one way a president can delay the implementation of a Supreme Court decision. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid presidential mechanism (e.g., slow rulemaking, selective enforcement, narrow interpretation, litigation strategy).

1 mark: Explains how that mechanism delays or limits practical compliance.

Analyse how state resistance can affect the real-world impact of a Supreme Court ruling. In your answer, refer to two distinct forms of resistance. (5 marks)

1 mark: Identifies first distinct form of state resistance (e.g., procedural obstacles, narrow compliance, policy repackaging, local noncooperation, strategic litigation).

1 mark: Explains how the first form reduces/delays the ruling’s effect.

1 mark: Identifies second distinct form of resistance.

1 mark: Explains how the second form reduces/delays the ruling’s effect.

1 mark: Overall analysis linking resistance to uneven/patchwork implementation or the need for further litigation/remedies.