AP Syllabus focus:

‘Congress, the president, and the courts use formal and informal powers over the bureaucracy to maintain accountability despite competing interests among the branches.’

Accountability in the federal bureaucracy is maintained through shared powers across the branches. Each branch uses distinct tools to monitor, direct, constrain, and review agency actions while pursuing its own political and constitutional priorities.

What “bureaucratic accountability” means in a shared-power system

Bureaucratic accountability: The requirement that agencies and officials explain and justify their actions and face consequences if they misuse authority, violate law, or diverge from elected branches’ policy goals.

Because the bureaucracy sits in the executive branch but implements laws written by Congress and interpreted by courts, accountability is inherently interbranch: control is fragmented, contested, and continuous.

Congress: Tools to monitor, direct, and punish noncompliance

Formal powers

Legislation and statutory design

Congress can write clearer mandates, narrow or expand delegated discretion, and impose reporting requirements.

Congress can create or restructure agencies and set procedural constraints (deadlines, consultation rules, transparency requirements).

Oversight and investigations

Committees hold hearings, demand documents, and compel testimony to detect waste, drift, or misconduct.

Oversight can be routine (monitoring) or crisis-driven (high-profile investigations).

Appropriations (“power of the purse”)

Congress can increase, reduce, condition, or deny funding to steer implementation.

Authorization vs. appropriation: authorisation permits programmes; appropriations provide money, making appropriations a strong compliance lever.

Informal and political tools

Casework and constituency pressure can surface implementation failures and push agencies to adjust enforcement.

Public messaging (letters, press conferences) can raise the political costs of bureaucratic choices.

Senate confirmation and advice (where applicable) can pressure agencies indirectly through leadership selection and scrutiny of nominees’ priorities.

The President: Tools to supervise and coordinate implementation

Formal powers

Appointment and removal

The president appoints many top officials who shape agency priorities; removal authority can discipline or replace leaders (though some positions have statutory protections).

Directives and management

Presidents use executive orders, memoranda, and other directives to set enforcement priorities and organise interagency coordination.

Centralised review through executive management can standardise implementation across the bureaucracy.

Informal powers

Persuasion and bargaining with agency leaders: aligning bureaucratic choices with the president’s agenda without new legislation.

Agenda-setting and publicity: using national attention to pressure agencies to act quickly, emphasise certain violations, or deprioritise others.

Internal performance expectations: setting metrics and deadlines to induce compliance and responsiveness.

The Courts: Tools to enforce legality and procedural compliance

Judicial review of agency action

Courts help maintain accountability by ensuring agencies act within constitutional and statutory limits and follow required procedures.

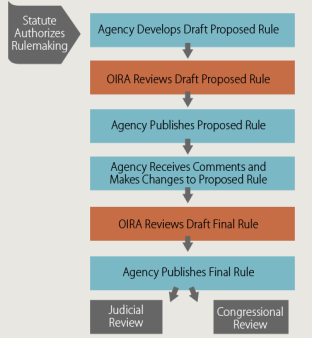

CRS’s “The Rulemaking Process” diagram summarizes the core stages of federal notice-and-comment rulemaking (proposal, public comment, and publication of a final rule). It helps connect bureaucratic policymaking to the legal standards courts apply when reviewing whether an agency followed required procedures and stayed within statutory authority. Source

Courts may:

Invalidate regulations or enforcement actions that exceed statutory authority.

Require agencies to provide adequate reasoning and evidence, especially when changing prior policies.

Enjoin unlawful actions, forcing revisions or halting implementation.

Limits and practical constraints

Courts typically rely on cases and controversies, meaning judicial checks are reactive and depend on litigation.

Remedies can be powerful but uneven: the effect of a ruling depends on compliance by executive officials and the feasibility of judicial supervision.

Why accountability is difficult: competing interests and shared control

Competing incentives: Congress may want strict enforcement in one area while the president prefers flexibility, or vice versa.

Multiple principals: agencies answer to Congress (funding and statutes), the president (management and leadership), and courts (legality), creating conflicting directives.

Policy drift vs. expertise: agencies need discretion to apply technical expertise, but discretion creates opportunities for mission creep, uneven enforcement, or politicised administration.

FAQ

Inspectors General conduct independent audits and investigations within departments.

They can:

uncover fraud/waste/abuse,

refer cases for prosecution or discipline,

issue public reports that prompt congressional and media scrutiny.

OIRA reviews significant draft regulations for cost-benefit considerations and consistency with presidential priorities.

It can return rules for revision, delay publication, and require interagency coordination, indirectly shaping what finally takes legal effect.

After the Supreme Court limited/ended Chevron-style deference, courts are more likely to independently interpret ambiguous statutes.

This can increase judicial checking of agency interpretations, but may also create uncertainty and more litigation over complex regulatory schemes.

Yes. Sunset clauses automatically terminate programmes or delegated authority unless reauthorised.

They force periodic review, generate oversight opportunities, and can deter long-term drift, but can also trigger instability or last-minute bargaining.

Some positions (often in independent regulatory bodies) have “for-cause” removal protections.

This can promote independence from short-term politics, but it reduces the president’s ability to discipline leaders quickly, creating a trade-off between neutrality and direct democratic control.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify two ways Congress can hold the federal bureaucracy accountable.

1 mark for identifying a valid congressional tool (e.g., oversight hearings/investigations; appropriations; legislation setting constraints; document requests/subpoenas; committee monitoring).

1 mark for a second distinct valid tool.

(6 marks) Explain how all three branches can check bureaucratic action, and analyse one reason why these checks may still fail to produce full accountability.

2 marks: Congress check explained (e.g., appropriations conditions and/or oversight and/or statutory limits).

2 marks: Presidential check explained (e.g., appointments/removal and/or executive directives and management).

1 mark: Judicial check explained (e.g., judicial review striking down unlawful agency actions).

1 mark: Analysis of a limitation (e.g., competing interests, fragmented control, courts are reactive, political incentives, or implementation complexity).