AP Syllabus focus:

‘National policymaking is constrained because the three branches share power. Negotiation, bargaining, and checks and balances can limit rapid policy change.’

American national policymaking is intentionally difficult because authority is divided among institutions with different constituencies, incentives, and tools. This design promotes deliberation, but it also creates delay, stalemate, and incremental change.

Shared powers as a deliberate constraint

Separation of powers creates competing centres of authority

Separation of powers: the constitutional division of government responsibilities among Congress, the presidency, and the judiciary so no single branch dominates lawmaking or enforcement.

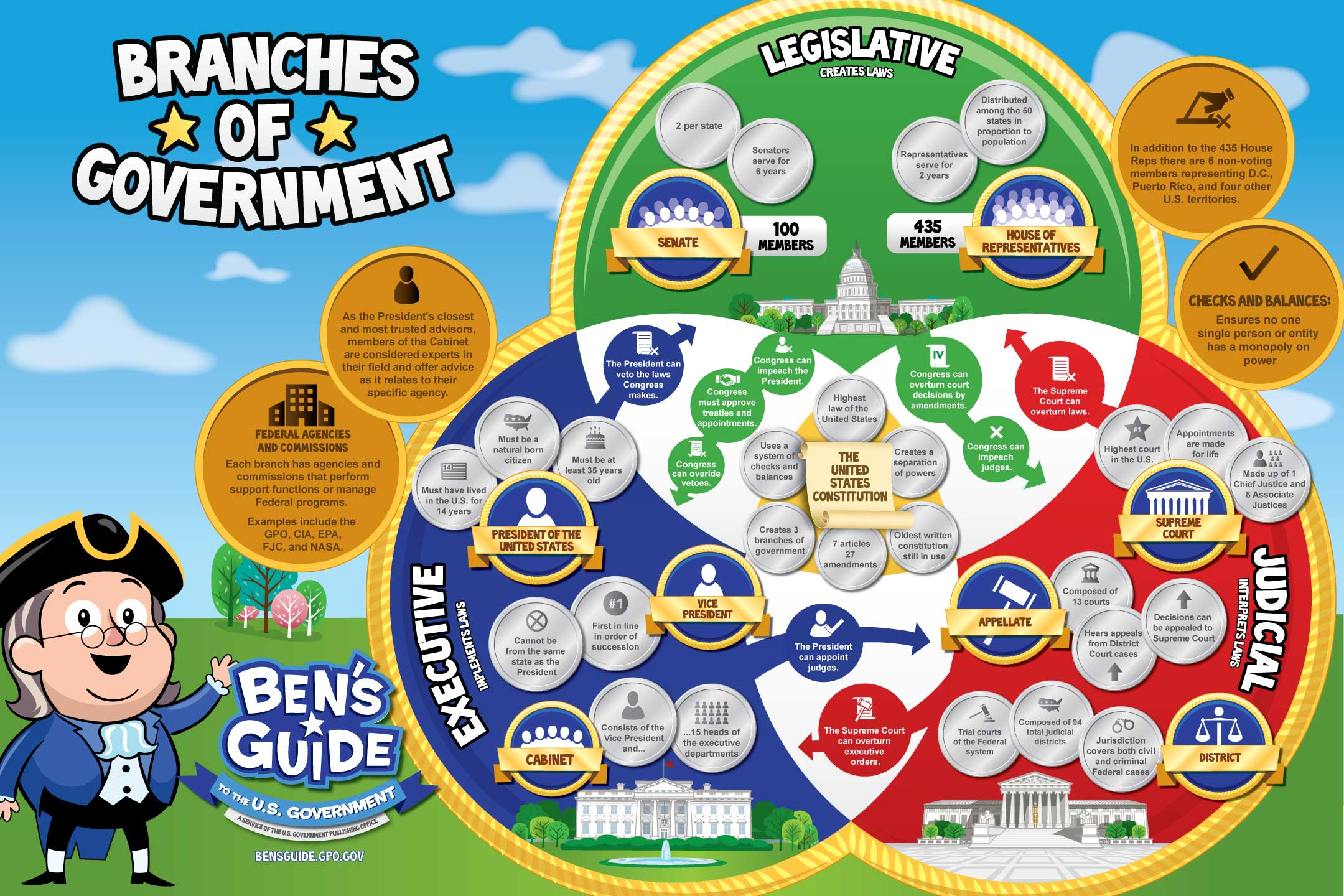

This diagram summarizes the three constitutionally distinct branches of the federal government—legislative, executive, and judicial—and highlights how their separate responsibilities are meant to prevent any one branch from accumulating excessive power. Read it as a structural map of "who does what" before focusing on how each branch can constrain the others. Source

Because each branch has distinct constitutional roles, major policy usually requires cooperation across institutions that may be controlled by different parties or motivated by different electoral pressures.

Checks and balances add hurdles to action

Checks and balances: a system in which each branch has formal and informal tools to limit, influence, or block the actions of the others.

These checks promote accountability, but they also increase the number of steps needed to enact or sustain policy.

Why shared powers slow policymaking

Multiple “veto points” protect the status quo

Veto point: a stage in the policymaking process where an actor can stop or substantially alter a proposal.

In the U.S. system, proposals face many veto points, which makes change harder than in parliamentary systems where the executive and legislative majority are fused.

Key veto points that commonly slow policy:

Bicameral passage: the House and Senate must both agree on identical text, forcing compromise across chambers.

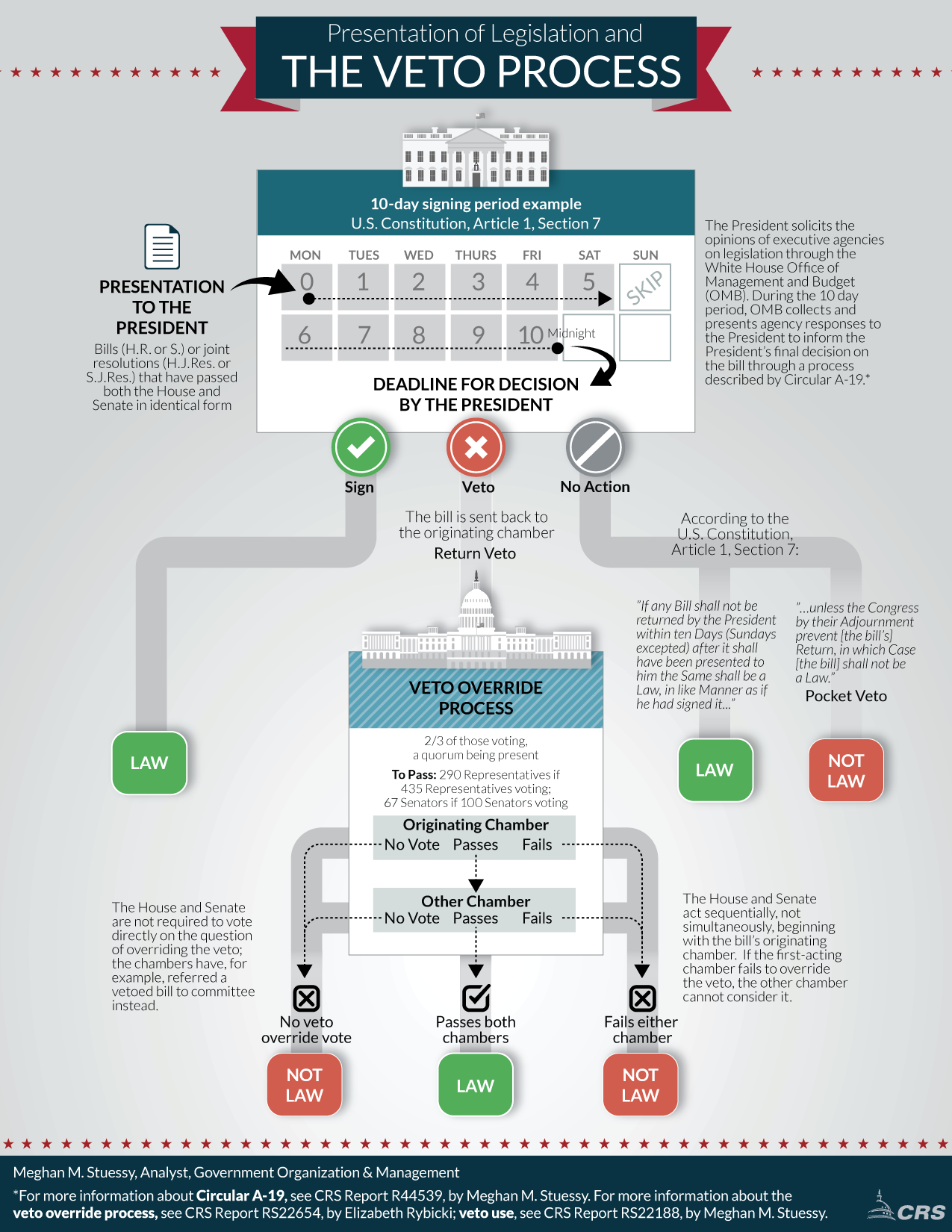

Presidential approval: the president can sign or veto, requiring supermajorities to overcome opposition.

This CRS process diagram traces what happens after a bill passes both chambers and is presented to the president, including the constitutional decision window, veto options, and the two-chamber override requirement. It visually reinforces why the presidential veto functions as a powerful veto point that can force renegotiation or halt policy change unless a supermajority coalition exists. Source

Judicial review: courts can invalidate policies that conflict with constitutional limits, creating uncertainty during drafting and implementation.

Negotiation is required, but it takes time

Shared power shifts policymaking toward negotiation and bargaining rather than simple majority rule. Policymakers must assemble coalitions that can survive:

internal disagreement within each institution,

disagreements between institutions, and

strategic resistance from actors who benefit from delay.

Practical ways bargaining slows change:

Iterative drafting: proposals are rewritten to satisfy pivotal actors, often narrowing the scope of policy.

Side payments and concessions: leaders may have to adjust timelines, enforcement, or funding to win support.

Message coordination: each branch has incentives to shape public perception, which can delay agreement while actors protect reputations.

Checks and balances encourage strategic obstruction

Because blocking policy can be easier than passing it, minority actors can use the system to stall opponents and extract concessions. The incentives are especially strong when:

the president and at least one chamber of Congress are held by different parties,

electoral competition rewards party differentiation over compromise, or

lawmakers prefer blame avoidance, letting another branch take responsibility for unpopular choices.

Obstruction does not always require open confrontation; simply refusing to act (not scheduling votes, not negotiating terms, not implementing aggressively) can be enough to slow outcomes.

Shared power produces incrementalism and delay

When rapid change is hard, policymakers often settle for incremental steps that can clear multiple hurdles. Even when change occurs, it may be:

narrower than initially proposed,

delayed to future dates to reduce immediate conflict, or

vulnerable to later reversal through elections, executive actions, or court rulings.

The overall result matches the syllabus focus: national policymaking is constrained because shared power forces continuous negotiation, bargaining, and checking, which limits rapid policy change.

FAQ

Deadlines concentrate bargaining by raising the cost of inaction.

They can:

force leaders to prioritise a deal over perfect policy,

create a clear ‘last acceptable’ compromise point,

shift leverage to actors controlling the final procedural steps.

They bundle urgent action with contested provisions, increasing pressure to compromise.

This can:

reduce the credibility of obstruction,

encourage cross-branch bargaining to avoid visible failure,

make outcomes more transactional than ideological.

Anticipating court challenges can slow drafting and implementation.

Policymakers may:

add severability clauses,

narrow policy to reduce constitutional risk,

delay enforcement while awaiting judicial clarity.

Norms (such as consultation expectations) affect trust and willingness to bargain.

When norms break down:

actors assume bad faith,

negotiation becomes more costly,

delays increase even without formal rule changes.

Ambiguity can be a strategic compromise when clear language would lose a veto-point actor.

It may:

paper over disagreements to secure passage,

postpone conflict to implementation,

allow multiple actors to claim partial credit.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Define a ‘veto point’ and explain one way veto points can slow national policymaking in the United States.

1 mark: Accurate definition of veto point (a stage where an actor can stop/alter policy).

1 mark: Identifies a valid veto point (e.g., bicameral agreement, presidential veto, judicial review).

1 mark: Explains how that point delays or blocks policy (e.g., forces compromise, requires additional majorities, creates uncertainty).

(6 marks) Explain two ways that separation of powers and checks and balances require negotiation and bargaining, and how this can limit rapid policy change.

1 mark: Correct use of separation of powers (powers divided across branches).

1 mark: Correct use of checks and balances (branches can block/influence each other).

2 marks: First way explained with clear link to negotiation/bargaining and slowed change (2).

2 marks: Second way explained with clear link to negotiation/bargaining and slowed change (2).