AP Syllabus focus:

‘When elections create divided government, partisanship often intensifies. Members of Congress may oppose presidential initiatives and appointments, especially during a lame-duck presidency.’

Divided government reshapes lawmaking by turning routine bargaining into open institutional conflict. Understanding why confrontation rises—and which tools Congress uses against the president—helps explain legislative stalemate, delayed appointments, and heightened partisanship.

Divided Government and Why It Matters

Divided government occurs when the presidency is held by one party while at least one chamber of Congress is controlled by the other party.

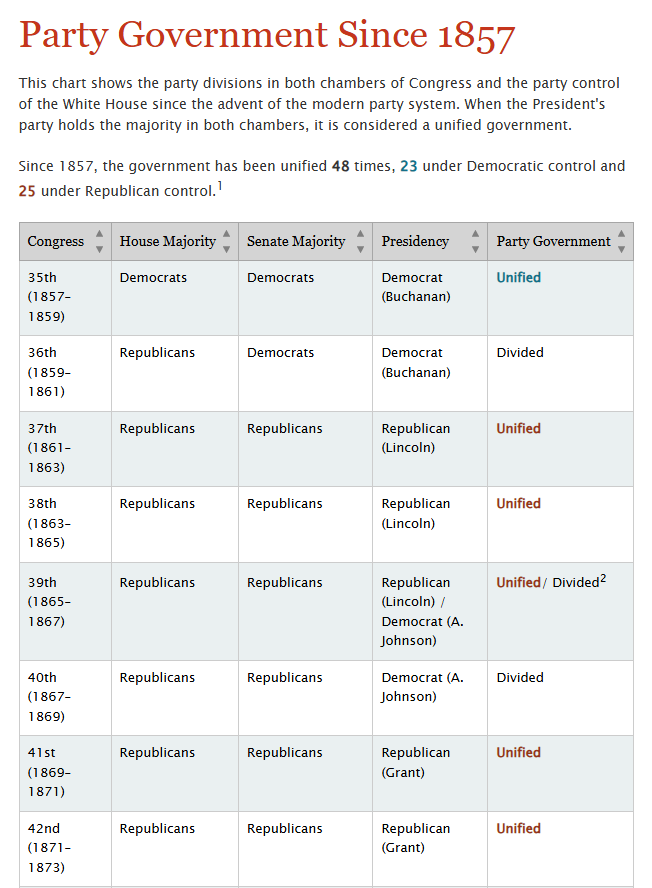

This timeline-style chart tracks party control of the House, Senate, and presidency across U.S. history, labeling each Congress as unified or divided government. It reinforces that divided government is not an anomaly but a repeated institutional condition created by separate elections and staggered terms. Use it to connect the concept definition to real historical patterns of party control. Source

It is common in the U.S. because of separate elections, staggered terms, and different constituencies.

Divided government: Party control of the executive and legislative branches is split between parties (e.g., one party holds the presidency and the other controls the House and/or Senate).

Why partisanship often intensifies

Divided government increases incentives to:

Blame the other side for policy problems and claim credit for blocking unpopular proposals.

Prioritise party brand and future elections over cross-party compromise.

Use procedural and institutional weapons rather than coalition-building.

This fits the syllabus emphasis that “partisanship often intensifies” when elections produce divided government.

How Congress Confronts the President

Confrontation is most visible when Congress chooses to oppose presidential initiatives and appointments rather than co-govern.

This diagram organizes major categories of congressional activity—legislating, representing constituents, exercising constitutional powers, and balancing power. It helps explain why conflict under divided government often shows up as strategic use of institutional tools (hearings, budgeting, procedure) rather than simple policy negotiation. Read it as a conceptual map of Congress’s leverage points against the executive. Source

Blocking or reshaping presidential initiatives

Members of Congress can resist a president’s agenda by:

Refusing to consider proposed legislation or declining to schedule votes.

Passing bills that undercut the president’s priorities or force unpopular choices.

Using must-pass legislation (especially funding measures) to demand policy concessions.

Conducting high-salience hearings to criticise executive actions and shift public narratives.

Even when Congress cannot enact its preferred policy, it can raise the political cost of presidential action and reduce the president’s momentum.

Aggressive oversight as a tool of opposition

Under divided government, oversight is more likely to become adversarial because it can expose failures and weaken the president politically. Congress may:

Call executive officials to testify and demand documents.

Launch investigations that spotlight alleged mismanagement or misconduct.

Signal distrust of the administration to bureaucratic actors and outside stakeholders.

Appointments as a Key Flashpoint

Because many important positions require Senate approval, appointments are a frequent site of conflict in divided government.

How opposition shows up in confirmations

Confrontation can take the form of:

Delaying hearings or votes to leave offices vacant and reduce executive capacity.

Rejecting nominees seen as too ideologically extreme or politically risky.

Using confirmations to extract concessions on unrelated priorities (informal bargaining).

Confirmation struggles matter because staffing choices shape how faithfully and vigorously the executive branch carries out laws.

Lame-Duck Presidencies and Heightened Conflict

Conflict can become especially sharp when the president is politically weakened by time, scandal, low approval, or an impending transition.

Lame-duck presidency: A period when a president’s political influence declines (often late in a term or after an electoral defeat), reducing leverage over Congress and increasing vulnerability to opposition.

Why Congress may confront a lame-duck president more directly

During a lame-duck period, members of Congress may calculate that:

The president has less electoral leverage and fewer credible threats or rewards.

The party out of power benefits from running out the clock rather than compromising.

Blocking initiatives and appointments can shape the next administration’s options (e.g., leaving vacancies or delaying policy implementation).

This aligns with the syllabus focus that opposition to initiatives and appointments can intensify “especially during a lame-duck presidency.”

Policy Consequences of Divided Government

Divided government does not make lawmaking impossible, but it changes outcomes in predictable ways:

More gridlock on major, controversial proposals; more reliance on narrower, less transformative bills.

Increased use of messaging votes designed to signal party positions rather than become law.

Greater likelihood of short-term bargains (temporary extensions, partial compromises) rather than durable settlements.

Slower staffing and reduced administrative effectiveness when appointments stall, increasing reliance on acting officials.

FAQ

Voters may prefer moderation or checks and balances, choosing different parties for Congress and the presidency. Local candidate appeal and district partisanship can also differ from national preferences.

Delay can be strategic. Slowing the process can drain media attention, increase bargaining leverage, or keep agencies led by temporary officials with less authority to pursue major changes.

Committees control hearing schedules, subpoenas, and investigative focus. Chair priorities can steer oversight towards politically damaging issues for the president’s party opponents.

Presidents may choose more moderate nominees, pre-negotiate with key senators, or prioritise candidates with bipartisan credibility to reduce confirmation resistance.

Yes, when there is:

A shared crisis or deadline

Cross-party public pressure

Areas of overlapping ideology

Leadership willingness to trade concessions across issues

Practice Questions

Define divided government and identify one way it can increase confrontation with the president. (3 marks)

1 mark: Accurate definition of divided government (split party control between presidency and Congress/chamber).

1 mark: Identifies a valid confrontation method (e.g., blocking legislation, delaying confirmations, oversight investigations).

1 mark: Links divided government to increased confrontation (e.g., partisan incentives/strategic opposition).

Explain two ways divided government can lead Congress to oppose presidential initiatives and appointments, and explain why this may intensify during a lame-duck presidency. (6 marks)

2 marks: Explains one method of opposing initiatives (e.g., agenda control, refusal to vote, attaching conditions) with clear linkage to divided government.

2 marks: Explains one method of opposing appointments (e.g., delaying hearings/votes, rejecting nominees) with clear linkage to divided government.

2 marks: Explains why lame-duck status can intensify conflict (reduced leverage, incentives to wait out president, shaping successor’s options).