AP Syllabus focus:

‘Legislators’ accountability depends on how they view representation. Trustees rely on their judgment, delegates follow constituent preferences, and politicos combine both approaches depending on the issue.’

Members of Congress constantly balance personal judgment, constituent opinion, and political realities.

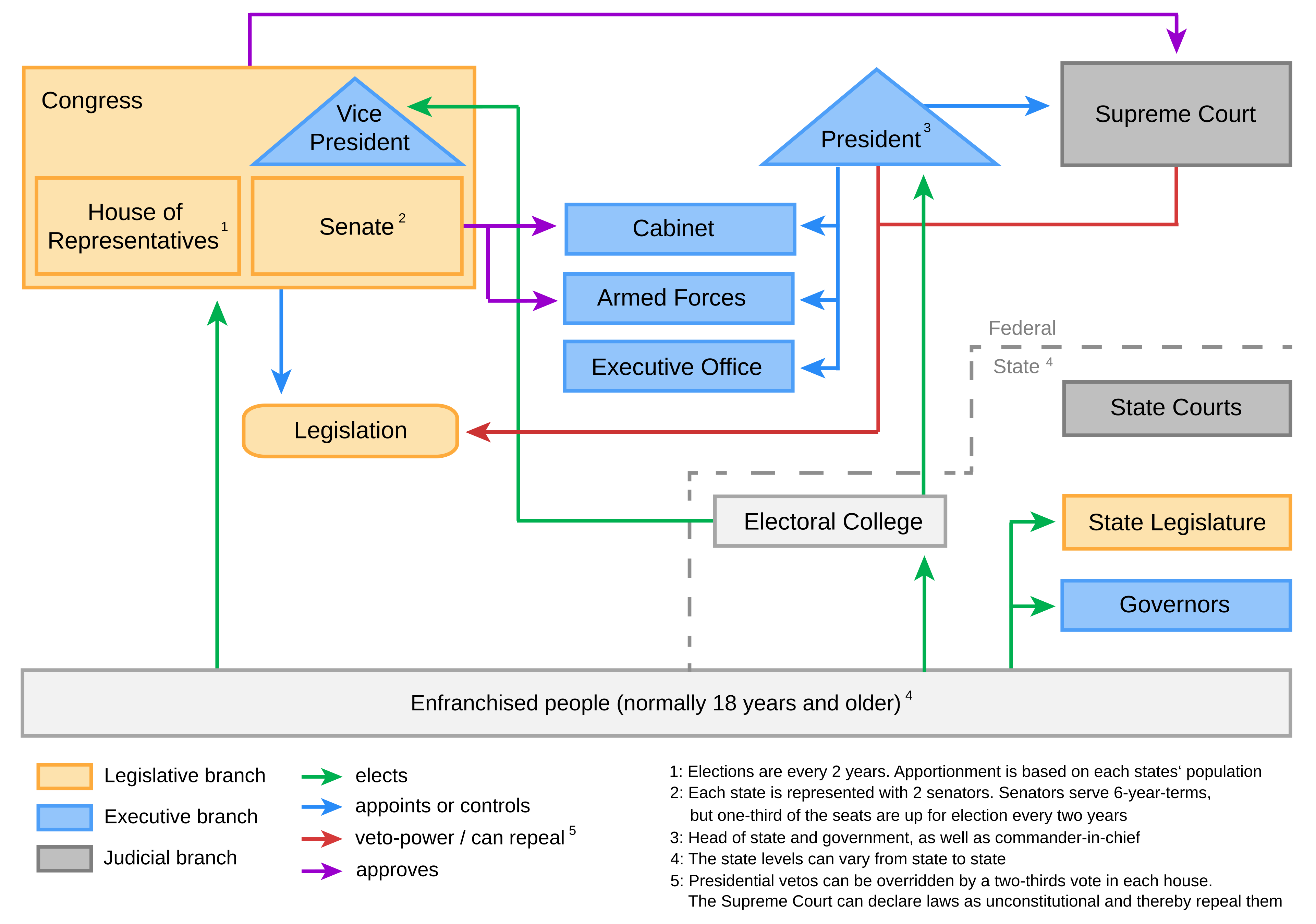

Flowchart overview of the U.S. political system, showing major institutions and how authority and accountability move among voters, elections, and governing bodies. It helps situate representation models in a concrete institutional setting: legislators’ choices are shaped not just by ideas about representation, but also by formal connections to constituents through electoral mechanisms. Source

These competing pressures shape how lawmakers define “good representation” and how voters and opponents evaluate their choices.

The representation problem: who should guide policy?

Representation is not just voting the “district’s will.”

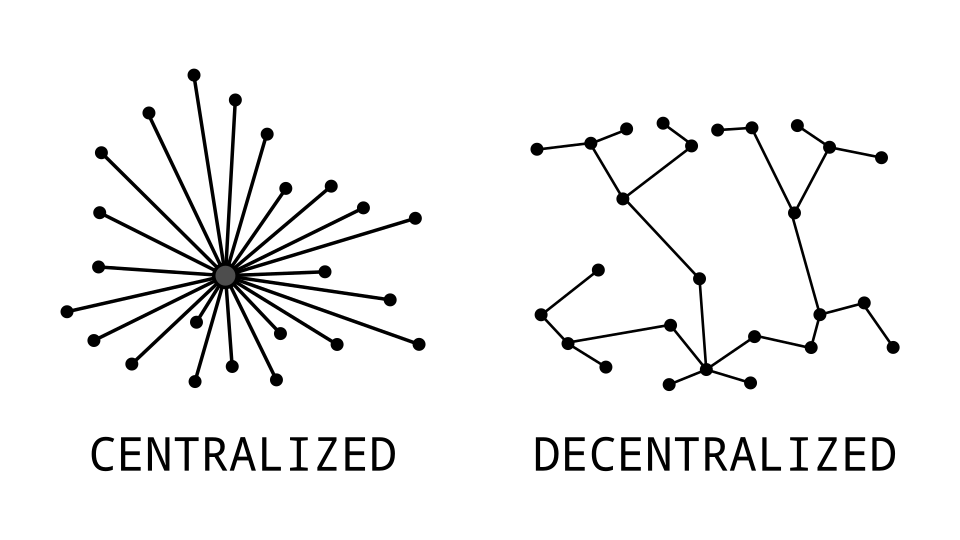

Side-by-side schematic contrasting centralized and decentralized decision-making structures. As an analogy for representation models, it makes the tradeoff between concentrated expert judgment and dispersed popular control visually intuitive—mirroring the tension between trustee-style independence and delegate-style responsiveness. Source

Legislators must decide how much weight to give to constituent preferences versus their own expertise and values, especially when opinions are unclear or divided.

Constituency: The people a legislator represents (typically everyone in the district or state), whose opinions and interests can influence the legislator’s policy choices.

A key AP focus is legislators’ accountability—whether voters can reasonably reward or punish a lawmaker based on how the lawmaker believes representation should work.

Accountability and role orientations

A legislator’s role orientation (trustee, delegate, or politico) affects:

How they justify votes (principle, district opinion, or a mix)

How they communicate (explaining decisions vs. echoing demands)

How constituents judge them (results, responsiveness, or both)

Trustee representation

In the trustee view, legislators prioritize independent judgment, arguing that voters elect them for their decision-making ability, not as a polling instrument.

Trustee model: A model of representation in which a legislator uses their own judgment to make policy decisions, even when that conflicts with short-term constituent opinion.

Trustee-style reasoning is most likely when:

Issues are complex/technical (limited public information or shifting evidence)

Constituents are divided (no clear “district position” exists)

A lawmaker believes a decision involves long-term national interest or constitutional principles

Trustee representation can strengthen deliberation, but it can also create vulnerability if constituents interpret independence as being out of touch.

Delegate representation

In the delegate view, legislators treat constituent preferences as the primary guide, emphasizing responsiveness and popular control.

Delegate model: A model of representation in which a legislator closely follows constituent preferences and views their role as carrying out the district’s will.

Delegate-style representation is most likely when:

An issue is high-salience (widely noticed and emotionally important)

District opinion is clear and measurable (consistent messages from voters)

Electoral incentives increase the value of visible responsiveness

The delegate model highlights democratic responsiveness, but it can reduce space for compromise if a legislator fears backlash for any deviation from constituent demands.

Politico representation (blended approach)

Many legislators behave as politicos, shifting between trustee and delegate roles depending on the situation.

Politico model: A model of representation in which a legislator alternates between trustee and delegate behaviour depending on the issue, context, and political incentives.

The politico approach reflects a practical reality: representation often requires multiple strategies, because “the constituency” is rarely a single unified voice.

What shapes whether a lawmaker acts as a trustee, delegate, or politico?

Common pressures that push lawmakers toward one role or another include:

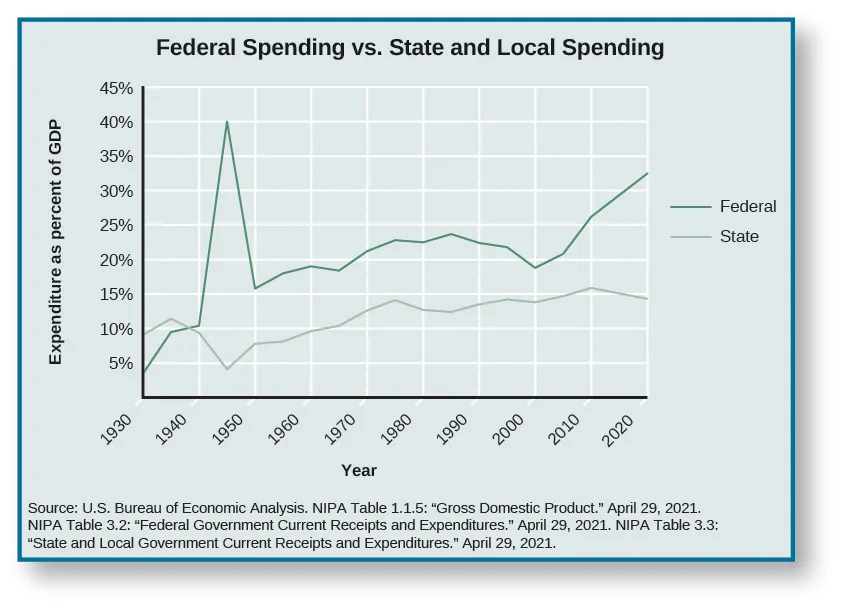

Time-series line graph comparing federal spending with state and local spending (as a percent of GDP) across multiple decades. It provides a concrete example of how long-run policy trends can raise the stakes of certain issues—helping explain why lawmakers may adopt more delegate-like responsiveness on high-attention topics and more trustee-like judgment on complex fiscal governance questions. Source

Issue salience: Higher attention tends to encourage delegate behaviour; low visibility can permit trustee decisions.

Clarity of constituent opinion: Clear majorities are easier to follow; mixed signals invite trustee reasoning or selective responsiveness.

Legislator expertise and information: Greater expertise can encourage trustee choices, especially on policy details.

District/state diversity: More diverse constituencies make it harder to identify one “will of the people,” encouraging politico balancing.

Electoral vulnerability: Competitive seats increase incentives to emphasise responsiveness and avoid unpopular independence.

Interest alignment: If a lawmaker’s beliefs match constituent preferences, behaviour can look delegate-like even if motivated by trustee judgment.

How these roles connect to accountability

Because these models define “good representation” differently, accountability varies:

Trustee accountability: Voters assess outcomes, integrity, competence, and long-term judgment.

Delegate accountability: Voters assess responsiveness and whether the member “listened.”

Politico accountability: Voters assess issue-by-issue consistency, credibility, and whether the member’s trade-offs seem fair.

A central tension is that each model can claim democratic legitimacy—either through responsiveness (delegate), deliberation (trustee), or adaptation (politico).

FAQ

They may prioritise likely voters, highly engaged constituents, or groups most affected by the policy.

They can also use town halls, surveys, and staff feedback to identify intensity, not just majority views.

They often rely on indirect signals: volume of calls/emails, local media framing, stakeholder meetings, and patterns from prior elections.

These signals can be biased towards more active constituents.

Yes. They may vote independently on technical provisions while taking highly visible positions aligned with district sentiment to demonstrate responsiveness.

This is a common form of politico-style blending.

Primaries can increase pressure to satisfy partisan activists, making “constituent opinion” effectively narrower and more ideological.

This can push behaviour towards delegate-like responsiveness to the party base.

They typically use credit-claiming and explanation: emphasising long-term benefits, local impacts, endorsements, and shared values.

They may also increase district outreach to rebuild trust and signal attentiveness.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Define the trustee model and the delegate model of representation.

1 mark: Correct definition of trustee model (uses own judgement/independent decision-making).

1 mark: Correct definition of delegate model (follows constituent preferences).

1 mark: Clear contrast between the two (independence vs responsiveness).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) A senator votes for a complex infrastructure bill despite mixed opinion in their state, arguing the long-term economic benefits outweigh short-term complaints. Using the trustee, delegate, and politico models, explain which model best fits this behaviour and how it affects electoral accountability.

1 mark: Identifies trustee model as the best fit and links to independent judgement.

1 mark: Explains why delegate model is less applicable (mixed opinion/no clear instruction).

1 mark: Explains how a politico could justify switching approaches depending on issue salience or clarity.

1–3 marks: Explains accountability implications (voters judge competence/outcomes vs responsiveness; mixed signals complicate evaluation; credit/blame at election).