AP Syllabus focus:

‘Presidents use informal bargaining and persuasion to secure congressional action, leveraging relationships, public attention, and political incentives to move legislation.’

Presidents often cannot command Congress, so they rely on informal tools to get “yes” votes. Bargaining and persuasion translate the president’s priorities into legislative coalitions by mixing relationships, attention, and targeted incentives.

What “bargaining and persuasion” means in practice

The Constitution gives presidents formal powers, but lawmaking still requires congressional majorities. Informal influence is therefore central to governing, especially when policy is contested or Congress is closely divided.

Informal presidential powers: Influence tools not explicitly listed in the Constitution—such as bargaining, persuasion, and relationship-building—used to shape Congress’s choices and move policy.

Persuasion is often “wholesale” (shaping broad support), while bargaining is “retail” (securing individual members’ cooperation). Together, they help presidents secure congressional action even when they lack guaranteed votes.

Why Congress is the main target

Presidents bargain and persuade to:

Move priority legislation through committees and to floor votes

Reduce opposition or win cross-party support

Keep their party unified when factions threaten defections

Shape the content of bills through behind-the-scenes negotiation

Core resources presidents leverage

The syllabus emphasises three major leverage points: relationships, public attention, and political incentives. These work best when combined.

1) Relationships (access, trust, and information)

President Barack Obama meets with top congressional leaders in the White House Cabinet Room (July 13, 2011) to negotiate over the debt limit and deficit reduction. The image is a clear visual example of how presidents rely on personal access, trust, and ongoing elite relationships to bargain for legislative movement when formal authority alone is insufficient. Source

Presidents and their teams cultivate ongoing ties with:

Party leaders who control scheduling and strategy

Committee chairs who shape hearings, markups, and bill language

Rank-and-file members whose votes are needed in close contests

Relationship-based persuasion relies on:

Frequent contact (calls, meetings, invitations)

Policy expertise and briefings from the White House

Signalling respect for congressional priorities and district/state concerns

Personal relationships matter because legislators face different incentives than the president, including constituency pressures, donor networks, and party factions.

2) Public attention (changing the political cost of “no”)

Presidents can elevate issues to increase pressure on legislators by:

Framing an issue as urgent or morally compelling

Highlighting benefits to the national interest or local communities

Using major speeches, interviews, and events to sustain coverage

Public attention is a tool of persuasion because it can alter legislators’ calculations:

Supporting the president may become safer if the issue is popular

Opposing the president may become riskier if it draws negative scrutiny

Media focus can force members to take positions rather than delay

3) Political incentives (inducements and trade-offs)

Presidential bargaining frequently involves offering help or withholding it. Common incentives include:

Policy concessions (accepting amendments, narrowing scope, timing changes)

Credit-claiming opportunities (public praise, bill-signing visibility)

Electoral support (campaign appearances, fundraising help, endorsements)

Administrative cooperation (prioritising a member’s concerns in implementation)

Political capital: A president’s perceived influence and credibility that can be “spent” to persuade legislators, often shaped by approval ratings, party unity, and recent wins.

Political incentives work best when they align a legislator’s re-election goals with the president’s policy agenda.

How bargaining and persuasion typically unfold

Presidential influence is often iterative rather than one decisive moment:

Identify pivotal legislators (swing votes, faction leaders, key committees)

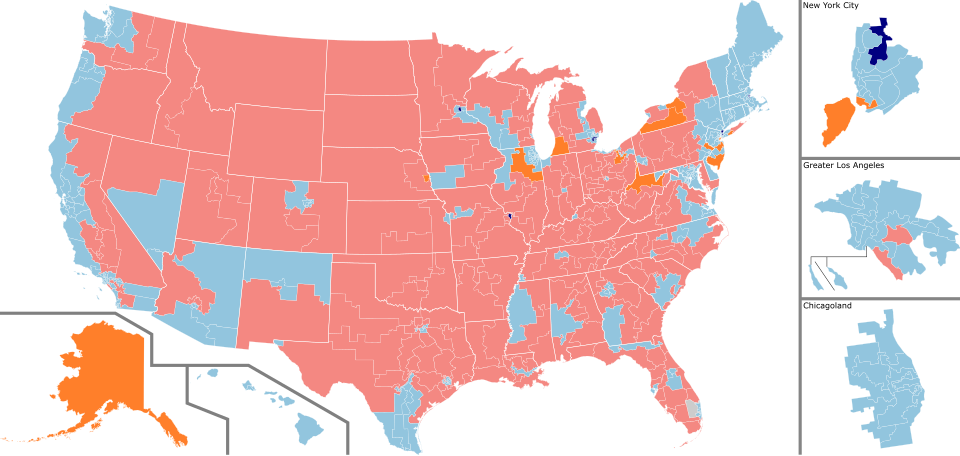

This map depicts a U.S. House roll-call vote (H.R. 3684, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, November 5, 2021) by party and vote choice. It visually reinforces how presidents and their teams must locate pivotal blocs and potential cross-party defections in order to target persuasion and “retail” bargaining effectively. Source

Set priorities (what is non-negotiable vs. tradable)

Use staff “whips” to count votes and map objections

Offer targeted concessions and seek reciprocal commitments

Reframe the bill publicly to broaden support when needed

Conditions that strengthen or weaken presidential influence

Bargaining and persuasion are more effective when:

The president’s party holds congressional majorities

Approval ratings are high (members anticipate electoral benefits)

The issue is salient and public attention favours action

The policy can be tailored to diverse coalitions without collapsing

They are less effective when:

Polarisation makes cross-party cooperation costly

Party leaders face internal revolts

Members fear primary challenges more than general elections

The president’s credibility is damaged by recent losses or scandals

Limits and trade-offs

Informal power is not cost-free. Concessions can:

Dilute policy goals

Anger parts of the president’s coalition

Encourage future demands from Congress

Public attention can also backfire by hardening opposition, especially if legislators view presidential pressure as intrusive or if the issue becomes a partisan identity marker.

FAQ

They act as constant intermediaries.

Track vote counts and objections

Relay offers/conpromises between offices

Maintain daily contact with leadership and committees

Prevent mixed messages by coordinating the administration’s position

They also identify which requests are feasible within agency and budget constraints.

Credibility comes from the president’s ability and willingness to deliver.

Factors include:

Control over campaign appearances and fundraising time

Capacity to provide public recognition (visibility is scarce)

Administrative follow-through (agencies actually prioritise agreed items)

Consistency over time (not reversing positions after commitments)

Legislators respond to different electorates and risks.

A member may fear:

A primary challenge from ideological activists

Local economic interests harmed by the proposal

Party punishment for breaking unity

Losing committee influence or donor support

National popularity does not always translate into district/state safety.

They weigh:

Vote margin (how many persuadables exist)

Agenda priority (core promise vs. expendable item)

Coalition fragility (whether concessions splinter supporters)

Timing (deadlines, media cycles, election proximity)

Pressure is likelier when compromise would undercut the policy’s purpose.

Yes.

Repeated negotiations can:

Build reputations for reliability or hardball tactics

Create durable cross-branch working relationships

Set expectations about what the White House will trade

Shape future legislative access for allies and sceptics alike

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Explain one way a US president can use public attention to persuade Congress to act on a legislative proposal. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid method (e.g., nationally televised speech, public campaigning, directing media focus to the issue).

1 mark: Explains how it changes congressional incentives/costs (e.g., raises electoral pressure, increases salience, makes opposition riskier).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Analyse how presidents use relationships and political incentives to bargain with members of Congress in order to secure congressional action. In your answer, refer to two distinct mechanisms. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Describes relationship-building (access, trust, regular contact with leaders/committee chairs) linked to legislative movement.

1–2 marks: Describes political incentives (policy concessions, credit-claiming, electoral support) linked to individual vote choice.

1–2 marks: Analysis showing how the two mechanisms interact to form a coalition (e.g., relationships identify needs; incentives satisfy them), explicitly tied to securing action.