AP Syllabus focus:

‘Executive orders are an implied presidential power used to manage the federal government. They can stem from vested executive power or from authority delegated by Congress.’

Executive orders are a primary way presidents direct the executive branch. They help translate broad priorities into immediate administrative action, shaping how agencies operate, enforce rules, and allocate attention within existing law.

What Executive Orders Are (and Aren’t)

Core purpose: managing the executive branch

Executive order: A written directive from the president to executive branch officials that manages operations of the federal government, relying on constitutional authority or power delegated by Congress.

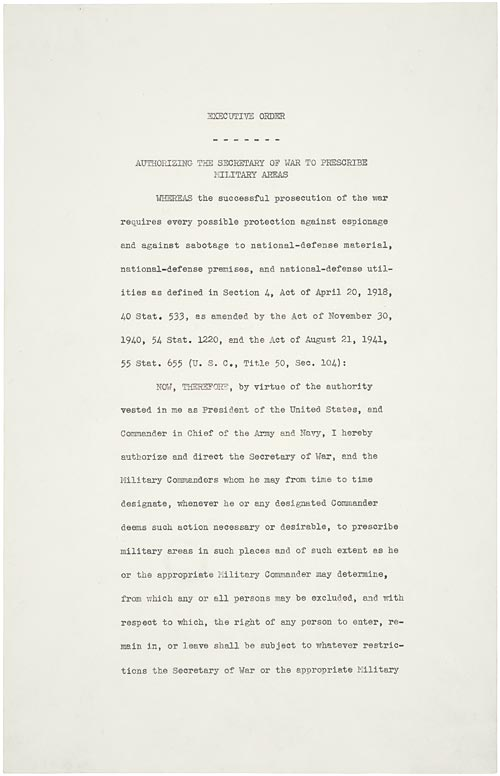

A high-resolution scan of Executive Order 9066 (February 19, 1942), showing the formal structure and legal language presidents use when issuing directives to the executive branch. Reading even the first page illustrates how executive orders typically invoke authority (“by virtue of the authority vested in me…”) and then direct officials on implementation. This makes the “written directive” definition tangible and shows how orders can produce far-reaching administrative action. Source

Executive orders are most common when presidents want speed, clear lines of authority, and uniform administration across the bureaucracy.

Limits built into the concept

Executive orders do not create new constitutional powers or replace statutes. To be durable, they must connect to:

Vested executive power (the president’s Article II authority to execute the laws and supervise the executive branch), or

Delegated authority (power Congress gives the executive branch through statutes, often leaving implementation details to agencies)

Where Executive Orders Get Their Authority

Vested executive power (constitutional grounding)

Presidents often justify executive orders as necessary to:

Direct cabinet departments and agencies

Standardise internal procedures (hiring practices, reporting requirements, enforcement priorities)

Coordinate national administration through executive offices and interagency processes

Because this authority is implied rather than exhaustively listed, disputes often hinge on whether an order is genuinely administrative or effectively legislative.

Delegated authority (statutory grounding)

Congress routinely passes laws that require executive implementation. An executive order may:

Specify which agency will lead implementation

Set timelines, compliance expectations, or coordination rules

Establish enforcement priorities consistent with statutory goals

In practice, executive orders can be strongest when they clearly cite statutory authority and align with the language and purpose of the underlying law.

How Executive Orders Work in Government

Typical pathway from order to action

President issues an order, usually drafted with legal review to reduce vulnerability

Agencies interpret the directive and translate it into internal guidance, memos, or implementation plans

Agency actions may include reorganising work, shifting enforcement emphasis, or initiating regulatory steps where authorised

Even when an order is legally valid, implementation depends on administrative capacity, clarity of instructions, and cooperation across the bureaucracy.

Why presidents rely on executive orders

Speed and visibility: action without waiting for a bill to pass

Control of the bureaucracy: aligning agency behaviour with presidential priorities

Policy signalling: setting expectations for executive branch decision-making

Executive orders are especially attractive in polarised environments where passing detailed legislation is difficult, but they still operate within the boundaries of existing legal authority.

Constraints and Vulnerabilities

Legal and political fragility

Because executive orders are not statutes, they can be:

A Library of Congress political cartoon (via the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center) depicting conflict over presidential influence and institutional resistance during the 1937 court-packing controversy. As a visual, it highlights the separation-of-powers reality that presidential initiatives can face pushback from other branches. This connects directly to why executive orders are politically and legally vulnerable even when they are fast and unilateral. Source

Challenged in court if alleged to exceed constitutional or statutory authority

Undercut by bureaucratic resistance, slow implementation, or conflicting agency missions

Reversed or modified by later presidents, especially when the order rests mainly on discretionary administrative control rather than explicit statutory commands

Practical importance for AP Gov

To evaluate an executive order, focus on two questions:

Is the president acting from vested executive power or delegated authority?

Does the order plausibly manage execution of the law, rather than create new law?

FAQ

Executive memoranda are also presidential directives, but are often less formal in style. Both can direct agencies; legal effect depends on underlying authority, not the document’s title.

No. Many only change internal management (reporting, coordination, priorities). Rule changes usually require separate processes if statutes demand formal procedures.

Clear linkage to constitutional responsibility or an explicit statutory delegation, careful legal drafting, and a record showing the order manages execution rather than creating new law.

Often less directly. Independent agencies may resist or be partially insulated by statute, though presidents can still influence through appointments, budgeting, and coordination requests.

They can redirect enforcement emphasis, reorganise responsibilities, or prioritise resources—administrative choices that significantly shape outcomes within the same statutory framework.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define an executive order and identify one source of authority for it.

1 mark: Accurate definition (presidential written directive to manage the executive branch/federal government).

1 mark: Identifies a valid authority source (vested executive power or authority delegated by Congress).

(5 marks) Explain how executive orders allow a president to manage the federal government, and analyse one reason their impact may be limited.

1 mark: Explains they direct executive agencies/officials to implement priorities.

1 mark: Explains they can structure coordination, procedures, or enforcement within the bureaucracy.

1 mark: Links authority to either vested executive power or congressional delegation.

2 marks: Analyses one limiting factor (e.g., legal challenge if beyond authority; dependence on agency capacity/compliance; reversibility by future presidents), with clear cause-and-effect.