AP Syllabus focus:

‘Courts continually interpret and apply the Bill of Rights, so its protections can expand, narrow, or shift in practice.’

Courts do not “rewrite” the Bill of Rights, but their interpretations determine what constitutional protections mean in real disputes. Over time, judicial reasoning, precedent, and changing facts reshape how rights are enforced and limited.

The Court’s role: turning text into enforceable rules

The Bill of Rights contains broad phrases (for example, “unreasonable searches” or “freedom of speech”) that require judicial interpretation when government action is challenged.

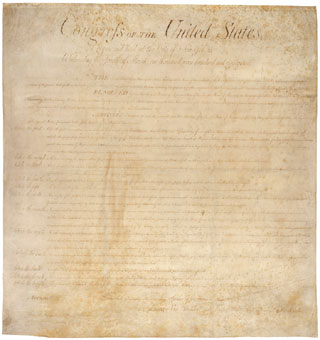

This image shows the original engrossed Bill of Rights (Congress’s 1789 proposal of amendments, ten of which became the Bill of Rights). Using the actual constitutional text helps emphasize the key idea in constitutional law: the words remain constant, but courts’ interpretations translate broad phrases into enforceable rules that can shift over time. Source

Judicial review and constitutional meaning

Judicial review: The power of courts to decide whether government actions are constitutional and to invalidate actions that conflict with the Constitution.

Through judicial review, courts translate constitutional principles into legal standards that lower courts and government officials can apply.

The image shows the west façade of the Supreme Court of the United States, the institutional setting for landmark constitutional decisions. Pairing the building with the concept of judicial review reinforces that the Court’s authority operates through published opinions and precedent that bind or guide lower courts. Source

Precedent and stability vs change

Precedent: A prior judicial decision that guides later cases with similar facts or legal issues.

Following precedent promotes predictability, but precedent can also be narrowed, distinguished (treated as different), or overturned, allowing constitutional protections to expand, narrow, or shift in practice.

How interpretations change over time

Courts shape the Bill of Rights through recurring methods that affect the scope of rights.

Competing interpretive approaches

Justices often differ on how to read constitutional text:

Textual and historical approaches emphasise ordinary meaning and founding-era context.

Living constitutional approaches emphasise how broad principles apply to modern realities (technology, social norms, new government practices).

These approaches can lead to different outcomes even when judges agree the Bill of Rights is binding law.

Tests and standards that evolve

Rather than issuing one-time definitions, courts develop doctrinal tests (rules for deciding future cases). Over time, the Court may:

Replace an older test with a new one (changing what government must prove)

Reinterpret key terms (changing what counts as a burden on a right)

Adjust how much deference is given to legislatures or executives

For example, speech doctrine shifted from more permissive restrictions on dangerous expression (e.g., Schenck v. United States) to stronger protection against punishment of advocacy unless it is likely to produce imminent lawless action (e.g., Brandenburg v. Ohio). The text stayed the same; the operational rule changed.

How facts and technology push new rulings

Even when the Court claims to follow the same principle, new contexts can change outcomes.

New forms of government power

As policing, surveillance, and communication methods change, courts must decide whether older protections apply to new practices. This can produce:

Expansion of protections to cover new settings

Narrowing when the Court treats a modern practice as outside earlier assumptions

Shifts in what counts as a meaningful intrusion on liberty

The Bill of Rights becomes practical through these case-by-case applications, which can differ across decades.

Societal norms and “reasonableness”

Some constitutional terms depend on judgement (for example, what is “reasonable” or what counts as an “excessive” punishment). Courts may look to:

Contemporary standards and practices

The severity of government interests (public safety, order)

The availability of less restrictive alternatives

This does not eliminate constitutional limits, but it can change how strict those limits are in practice.

The Court’s tools for expanding or narrowing rights

Even without overruling prior cases, courts can significantly reshape rights.

Distinguishing, narrowing, and overruling

Distinguishing: The Court treats a precedent as not controlling because the facts differ.

Narrowing: The Court keeps the precedent but limits it to a small category of situations.

Overruling: The Court explicitly rejects an earlier rule and replaces it.

Each method affects how broadly individuals can claim protection against government.

Balancing liberty against government interests

Many Bill of Rights disputes involve trade-offs between an asserted right and a stated government goal (security, public order, administrative efficiency). Courts influence outcomes by:

Defining how strong the government interest must be

Defining how direct the connection must be between the law and that interest

Deciding whether alternative policies would burden rights less

The “balance” can tilt depending on the Court’s membership, prevailing threats, and legal framing of the issue.

Why the Court’s composition and legitimacy matter

Because constitutional cases often involve judgement, changes in the Court can matter.

Appointments and interpretive direction

Presidents and senators influence constitutional development through judicial appointments. Over time, new majorities can:

Reinforce existing doctrine

Incrementally redirect doctrine

Rapidly change doctrine by overruling key precedents

Legitimacy and incrementalism

The Court often moves in steps to maintain institutional legitimacy:

Creating narrow rulings that avoid broad pronouncements

Allowing doctrine to develop through multiple cases

Signalling openness to future change without immediate reversal

This gradualism is a major reason Bill of Rights protections can shift in practice without a constitutional amendment.

FAQ

Most constitutional disputes end in district courts and circuit courts.

Circuit splits (different rules in different regions) can persist for years.

Even without Supreme Court review, lower-court interpretations shape policing, school policies, and regulations within their jurisdictions.

Amicus briefs (“friend of the court”) provide additional legal and factual arguments.

They can introduce broader policy implications, historical evidence, or technical context (e.g., how a technology works), which may influence the Court’s framing of the right.

The Court controls most of its docket through certiorari.

Common reasons to grant review include national importance, conflicting lower-court rulings, or unclear doctrine. Denials can leave significant constitutional questions unsettled.

It can narrow earlier rulings by redefining key terms, adding exceptions, or changing how a test is applied.

Over multiple decisions, this can effectively transform a right’s scope while keeping the earlier precedent formally “alive.”

A rule defines what the Constitution requires or forbids; a remedy determines what happens after a violation.

Courts can keep a right’s formal rule while limiting remedies (or vice versa), strongly affecting how meaningful the protection is in practice.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain how precedent can cause Bill of Rights protections to change over time.

1 mark: Identifies that courts follow earlier decisions (precedent) when deciding similar cases.

1 mark: Explains that precedent may be narrowed, distinguished, or overturned, which can expand or restrict how a right is applied in practice.

(6 marks) Using one Supreme Court case you have studied, analyse how judicial interpretation can shift the practical meaning of a Bill of Rights protection over time.

1 mark: Names a relevant case and links it to a specific Bill of Rights protection.

2 marks: Accurately explains the constitutional issue and the Court’s ruling in that case.

2 marks: Analyses how the ruling changed the operational rule/test or altered the balance between liberty and government power.

1 mark: Shows how this illustrates that protections can expand, narrow, or shift in practice (e.g., by comparison to earlier or later doctrine, even briefly).