AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Constitution includes the Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties and rights from undue government interference.’

The Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution to address fears of centralized power, secure ratification, and clearly state limits on government.

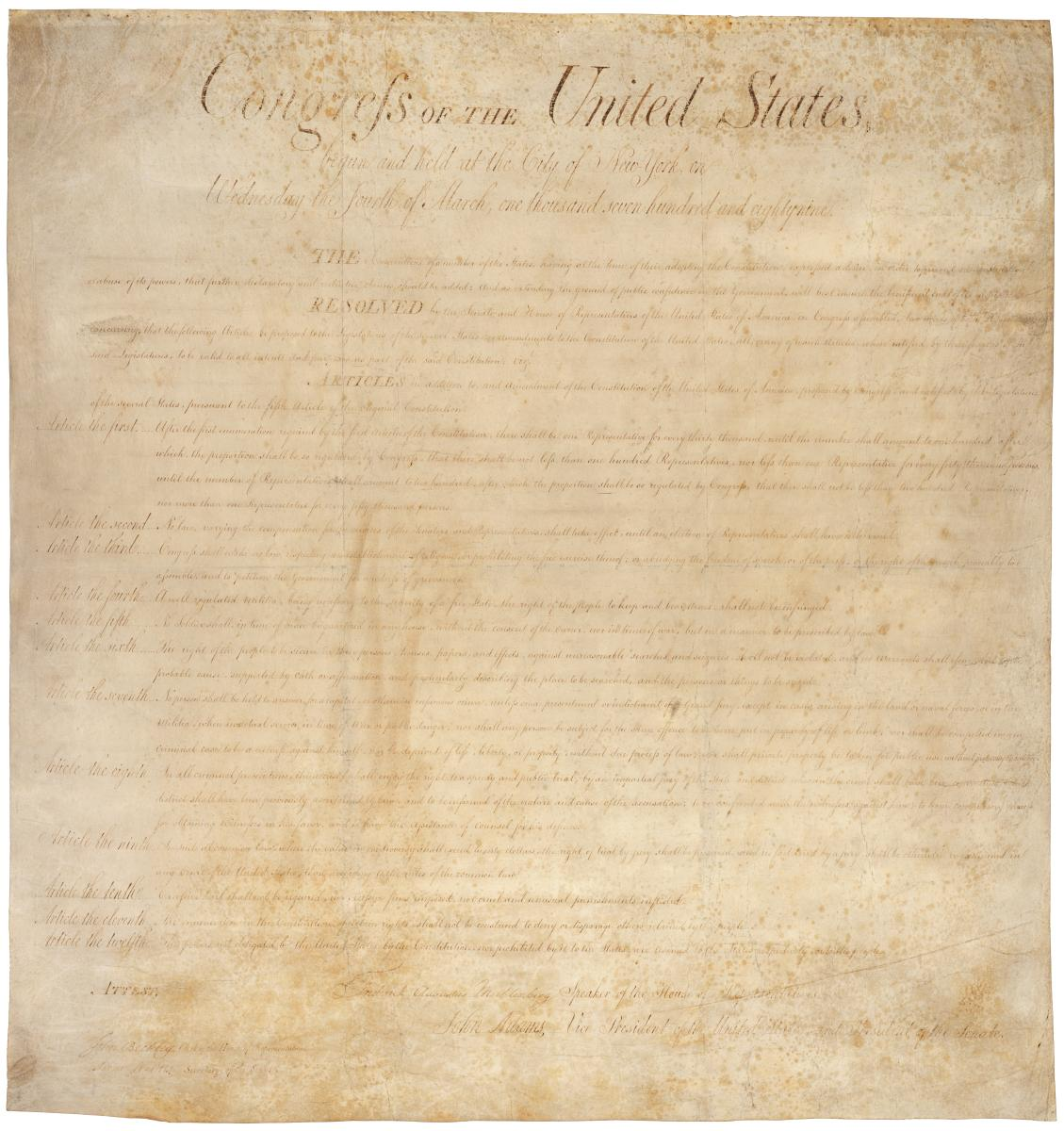

The engrossed 1789 Bill of Rights (Congress’s joint resolution proposing the amendments) shows how the first ten amendments were originally presented as explicit limits on federal power. Seeing the document format reinforces that these rights were written as enforceable constitutional restraints rather than ordinary statutes. Source

Its design reflects a commitment to individual liberty through enforceable constitutional restraints.

Why a Bill of Rights Was Demanded

The ratification problem

When the Constitution was proposed in 1787, many Americans worried the new national government would become too powerful. Under the Articles of Confederation, the national government was weak; the Constitution strengthened it through taxing power, a national executive, and federal courts. This raised the question: what would stop federal officials from infringing liberty?

Anti-Federalists argued that:

A stronger central government could resemble the British system Americans had resisted.

Broad constitutional powers (like necessary and proper) might justify intrusive laws.

Without explicit protections, individual rights could be left to shifting political majorities.

Federalists generally believed the Constitution already limited government enough through separation of powers and checks and balances, but political reality mattered: several states conditioned support on adding amendments protecting rights.

This diagram summarizes separation of powers by distinguishing the legislative, executive, and judicial functions. It visually reinforces the Federalist claim that constitutional structure itself restrains government—an argument that shaped (but did not replace) the push to add a Bill of Rights. Source

A bargain to secure legitimacy

The promise of a bill of rights was a major political compromise. It reassured skeptical states and citizens that the new Constitution was not only a plan for governing, but also a binding statement of what government could not do.

Purpose: Protecting Liberty by Restricting Government

The syllabus emphasis is that the Bill of Rights exists “to protect individual liberties and rights from undue government interference.” This purpose is reflected in how the amendments are written: most are prohibitions on government, not grants of power.

Rights as “negative” limits

Many of the first ten amendments are framed as restrictions on government action (for example, “Congress shall make no law…”). The design assumes that:

Government power is necessary for order and security, but dangerous if unconstrained.

Enumerating specific protections helps prevent officials from claiming unlimited authority.

Constitutional rights should be enforceable against government, not dependent on goodwill.

Bill of Rights: The first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution, added in 1791, that set out specific protections for individual liberty by limiting federal government power.

This Library of Congress image shows a reproduction of the Bill of Rights, emphasizing the text-as-document nature of constitutional rights. It supports the idea that the Bill of Rights was meant to be read and invoked as binding law—especially in disputes over whether government action crosses constitutional boundaries. Source

A key idea behind the Bill of Rights is that liberty is safer when certain areas—belief, expression, personal security, fair legal process—are placed beyond ordinary politics.

Preventing “undue interference”

“Undue government interference” does not mean government can never regulate. It means the Constitution requires a justification and sets boundaries, especially where government action threatens:

Personal autonomy (control over one’s life and choices)

Political freedom (criticising officials, participating in public debate)

Legal fairness (protection against arbitrary punishment)

Design: Why List Rights at All?

Clarifying the relationship between people and government

The Constitution begins with popular sovereignty (“We the People”). The Bill of Rights reinforces that the people are not subjects; they are citizens with protected spheres of freedom. By listing rights, the Constitution communicates that:

Certain liberties are foundational, not optional.

Government must act through law and within limits.

Individuals have claims they can raise against government action.

Standardising protections across the new nation

Before the Bill of Rights, many states had declarations of rights. But state protections varied and did not directly restrain the federal government. The Bill of Rights created a shared national baseline for federal conduct—especially important as federal courts and federal law expanded.

Guarding against broad interpretations of federal power

The Constitution grants Congress significant authority (taxing, spending, regulating commerce). Critics feared these powers could be interpreted expansively to justify censorship, disarmament, or abusive criminal procedures. A bill of rights was designed to:

Reduce ambiguity about what government may not do.

Strengthen public confidence that power would be exercised narrowly.

Provide textual hooks for later legal enforcement.

Competing Arguments Shaping the Final Form

Anti-Federalist concerns

Anti-Federalists viewed a bill of rights as essential because:

History showed power tends to expand unless clearly limited.

Written guarantees could mobilise public resistance and judicial protection.

The new federal government was distant from citizens, making abuse harder to check politically.

Federalist cautions (and why they lost)

Some Federalists argued a bill of rights was unnecessary or even risky:

Because the federal government had enumerated powers, it had no authority to violate unlisted rights.

Listing some rights might imply other rights were unprotected.

Despite these concerns, the amendments were drafted to address them by limiting government in specific areas and reinforcing that the people retain rights beyond those listed.

Early Impact: A Practical Check on Federal Authority

Initially, the Bill of Rights was understood primarily as a constraint on the national government. Even so, it shaped American politics by:

Establishing liberty-protecting language that citizens could invoke.

Setting standards for acceptable federal lawmaking and enforcement.

Embedding the principle that constitutional government requires both power and restraint.

FAQ

Yes. Several state constitutions had declarations of rights, but they varied and did not directly bind the federal government.

He saw amendments as stabilising: they reduced opposition, strengthened legitimacy, and could channel disputes into constitutional rules.

Yes. Some proposals failed or were postponed; the final ten reflected political agreement rather than an exhaustive list of desired protections.

It served as a visible pledge that federal power had firm boundaries, helping sceptical citizens accept the new constitutional system.

Some feared it implied that unlisted rights were unprotected; this concern influenced how Americans debated the meaning of enumerating rights.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., to secure ratification; to limit federal power; to address Anti-Federalist concerns).

1 mark for explaining how that reason connects to protecting liberty from government interference.

Analyse how the purpose and design of the Bill of Rights reflect concerns about federal power during ratification. (5 marks)

1 mark for explaining ratification-era fear of centralised power.

1 mark for linking the Bill of Rights to securing legitimacy/ratification.

1 mark for explaining “negative” limits (rights framed as restrictions on government).

1 mark for explaining how listing rights constrains broad interpretations of federal authority.

1 mark for clear analytical linkage between purpose (prevent undue interference) and design (textual limits/enforceable claims).