AP Syllabus focus:

‘The civil rights movement of the 1960s—illustrated by Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”—shows how constitutional ideals can motivate activism.’

The 1960s civil rights movement linked protest to constitutional promises.

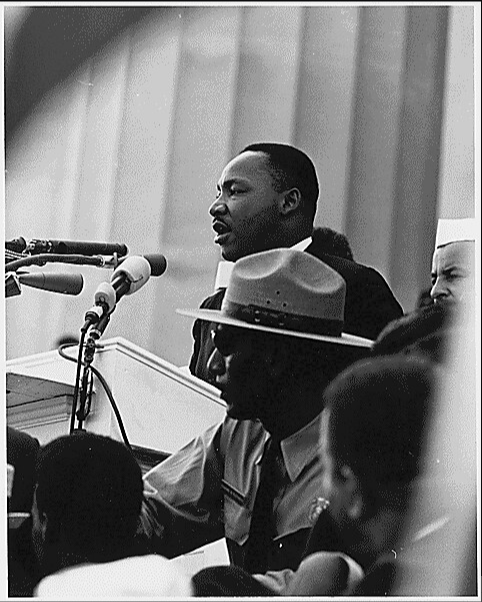

This National Archives photograph shows Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. The image captures how constitutional ideals were translated into collective action—mass assembly and public speech used to press the federal government toward enforceable guarantees of equal citizenship. Source

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” framed direct action as a democratic duty when governments fail to secure equal citizenship and basic liberties.

Constitutional ideals that energised activism

Civil rights activists argued that American constitutionalism contains enforceable moral commitments, especially equal citizenship and limited government. Movement leaders regularly invoked:

Fourteenth Amendment principles: states must provide equal protection and due process rather than maintain racial hierarchy.

First Amendment values: speech, assembly, press, and petition make public dissent legitimate and necessary in a democracy.

The idea of rule of law: law should be consistent, general, and fairly applied; when it becomes a tool of oppression, it loses legitimacy.

This framing mattered strategically: it portrayed demands not as special treatment, but as fulfilment of widely shared constitutional ideals.

Movement tactics as constitutional practice

Nonviolent direct action and democratic accountability

Nonviolent campaigns treated public protest as a way to force institutions to respond when normal channels were blocked (e.g., intimidation, exclusion, or delay). Common tactics included:

Boycotts to apply economic pressure while demonstrating collective capacity

Marches and demonstrations to claim public space and visibility

Sit-ins and picketing to challenge segregationist rules in everyday life

Jail-ins and willingness to accept arrest to highlight injustice

These tactics also leveraged publicity: by bringing conflict into view, activists encouraged broader citizens to evaluate whether government was living up to constitutional standards.

Why “law and order” arguments were central

Officials often justified restrictions on demonstrations as necessary for public order. Activists responded that order is not an end in itself; it must be weighed against constitutional commitments to liberty and equality. The movement therefore became a contest over what the Constitution requires in practice, not just what it says on paper.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail”: activism grounded in constitutional ideals

Context and purpose

King wrote the letter in 1963 after being jailed during protests in Birmingham, Alabama, replying to clergy who criticised demonstrations as untimely and disruptive. The letter’s key move was to defend protest as principled constitutional engagement when local political processes are unresponsive.

Unjust laws and the meaning of equality

King distinguished between just and unjust laws, arguing that unjust laws degrade human personality and impose unequal status. In constitutional terms, this echoes the claim that laws incompatible with equal citizenship violate the nation’s foundational commitments. His argument pressured readers to judge legality by its relationship to constitutional equality, not merely by whether authorities enacted it.

Civil disobedience as fidelity to democratic principles

Civil disobedience: A deliberate, public, nonviolent violation of law undertaken to protest injustice and to appeal to the community’s conscience, typically with willingness to accept legal consequences.

King presented civil disobedience as disciplined rather than anarchic: protesters act openly, use nonviolence, and accept punishment to demonstrate respect for law while condemning injustice. This posture reframed arrests as evidence of governmental failure to meet constitutional ideals.

“Wait” as denial of rights

A major theme is the critique of gradualism: when basic rights are persistently delayed, “wait” functions like a denial. This supports the broader syllabus point that constitutional ideals can motivate activism by supplying a standard against which to measure government inaction and by legitimising sustained collective pressure.

FAQ

He argued that the main barrier can be people who prefer “order” and gradualism over immediate justice.

This targets legitimacy: persuading mainstream audiences expands pressure on institutions.

It aligned tactics with claims about democratic rights and moral equality.

It also exposed disproportionate state responses, sharpening constitutional critiques.

It exemplified local resistance where negotiation failed and delay was routine.

That context supported the claim that normal political channels were functionally closed.

No. It distinguishes them, arguing some laws can be legally enacted yet fundamentally unjust.

The point is to evaluate law against higher principles of equal human worth.

It uses moral reasoning, personal experience, and audience-centred rhetoric.

These elements translate abstract constitutional ideals into urgent human stakes.

Practice Questions

Explain one way “Letter from Birmingham Jail” connects protest to constitutional ideals. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a relevant constitutional ideal (e.g., equal citizenship/equal protection; First Amendment freedoms; rule of law).

1 mark: Explains the connection (e.g., protest as petition/assembly; civil disobedience to highlight unjust laws inconsistent with equality).

Using “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” analyse how constitutional ideals can motivate and justify activism in the civil rights movement. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks: Accurate use of the letter’s arguments (e.g., unjust vs just laws; critique of “wait”; accepting arrest to demonstrate moral seriousness).

Up to 2 marks: Links those arguments to constitutional ideals (e.g., equal citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment; democratic accountability via First Amendment participation).

Up to 2 marks: Analysis of why this framing motivates activism (e.g., legitimises direct action when channels are blocked; mobilises public opinion by appealing to shared constitutional values).