AP Syllabus focus:

‘Advocacy for LGBTQ rights demonstrates how equal protection arguments can support movements seeking equal treatment under law.’

LGBTQ rights advocacy in the United States has relied heavily on constitutional litigation and coalition-based political strategies. A central legal tool has been the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of equal protection, used to challenge discriminatory state action.

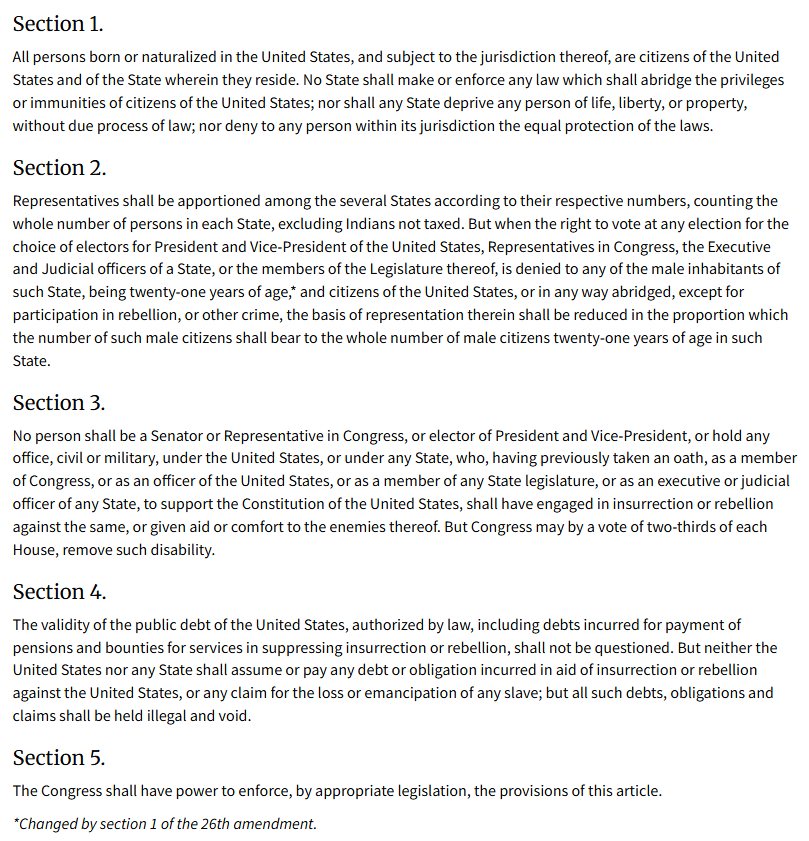

This image presents the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection language in its original constitutional-text format. Seeing the clause as enacted helps connect modern LGBTQ equal-protection litigation to the amendment’s core command that states may not deny equal protection of the laws. It is especially useful for distinguishing constitutional text from later judicial tests developed to apply it. Source

Equal Protection and LGBTQ Rights Claims

Core constitutional idea: equal treatment by government

Equal Protection Clause: The Fourteenth Amendment requirement that states treat similarly situated people alike, allowing distinctions only when government can justify them under the appropriate level of judicial scrutiny.

Because the clause restricts state government action, advocates often target laws and policies that classify people based on sexual orientation or gender identity, or that impose unequal burdens on LGBTQ people.

How advocates frame equal protection arguments

Common argumentative strategies include:

Classification argument: the law draws an impermissible line (explicitly or in effect) against LGBTQ people.

Animus argument: the law reflects bare desire to harm an unpopular group, not a legitimate public purpose.

Sex-discrimination analogy: discrimination against LGBTQ people can be argued as discrimination “because of sex,” strengthening the claim that heightened constitutional concern is warranted.

Fundamental fairness narrative: unequal access to core legal protections (family recognition, safety, participation in civic life) violates the Constitution’s commitment to equal citizenship.

Litigation as Movement Strategy

Why strategic lawsuits matter

LGBTQ advocacy groups have used test-case litigation to:

Create binding precedent that constrains states and lower courts.

Build incremental wins that shift doctrine and public understanding.

Combine constitutional claims with carefully chosen plaintiffs and fact patterns to highlight unequal treatment.

This approach often operates alongside electoral and legislative advocacy, but the equal protection clause is especially powerful when legislatures are unwilling to extend protections.

Landmark Supreme Court developments (equal protection-focused)

Key rulings frequently cited by advocates include:

Romer v. Evans (1996): struck down a Colorado amendment that broadly blocked anti-discrimination protections for gay and lesbian people, emphasising the absence of a legitimate governmental purpose and signalling concern with animus.

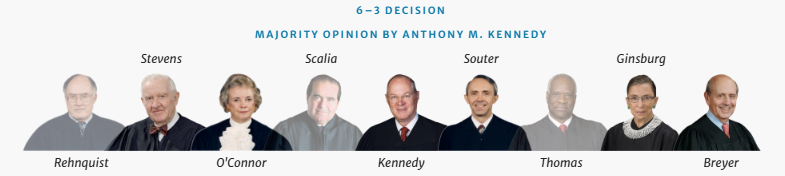

This case-page image summarizes Romer v. Evans with a clear decision layout, including the vote split and the justices’ alignment. It visually reinforces the institutional reality that equal protection doctrine is shaped through Supreme Court coalitions and written opinions, not just abstract principles. Pairing this with the notes’ “animus argument” shows how the Court can invalidate a law when it appears to target a politically unpopular group rather than serve a legitimate purpose. Source

United States v. Windsor (2013): invalidated a federal definition of marriage that excluded same-sex couples, reinforcing the constitutional problem of laws that impose unequal status and dignity on a targeted group.

Obergefell v. Hodges (2015): required states to license and recognise same-sex marriages; while grounded in both liberty and equality principles, advocates used equal protection reasoning to argue that denying marriage created an unconstitutional caste-like system.

These cases illustrate how movement advocacy uses equal protection to transform social claims into constitutional claims about equal legal standing.

Judicial Scrutiny and Ongoing Debates

Levels of scrutiny and why they matter

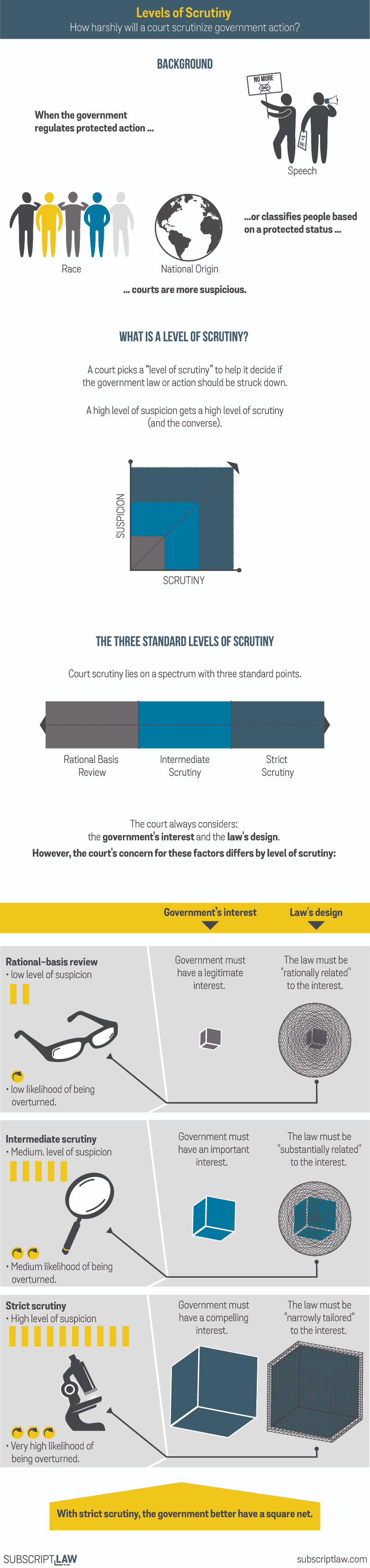

Equal protection analysis depends on the court’s chosen test (often described as rational basis, intermediate scrutiny, or strict scrutiny).

This chart compares the three main levels of equal protection scrutiny by pairing each with the government’s required objective (legitimate/important/compelling) and the required means–ends fit (rationally related/substantially related/narrowly tailored). It helps explain why advocates often fight over the level of scrutiny first, because that choice largely determines how demanding the constitutional review will be. Use it as a quick reference when evaluating how a court might assess an LGBTQ-related classification claim. Source

LGBTQ advocates frequently argue for more searching review when:

A group has experienced a history of discrimination.

The trait is irrelevant to one’s ability to participate in society.

Political processes have failed to protect the minority from majority decision-making.

Even when courts apply less demanding review, advocates can still win by showing the policy is arbitrary, overbroad, or motivated by impermissible purposes.

Movement impacts beyond the courtroom

Equal protection arguments also:

Provide constitutional language for public persuasion (“equal treatment under law”).

Help build coalitions by tying LGBTQ rights to broader American ideals of fairness and equal citizenship.

Generate policy spillovers as governments revise laws to avoid litigation risk.

At the same time, opponents often reframe disputes as protecting religious liberty, tradition, or democratic choice, keeping equal protection doctrine at the centre of ongoing conflict over the meaning of equality.

FAQ

They supply social science, historical context, and legal frameworks that help justices evaluate governmental justifications.

They can also signal broad elite support (business, military, faith groups), shaping how “reasonableness” and harm are understood.

Advocates may pursue narrower routes (animus, arbitrariness, or sex-discrimination framing) to win under existing doctrine.

This can reduce the risk of an adverse ruling that would set limiting precedent.

Claims often focus on whether policies classify by sex (triggering heightened review) or impose unequal burdens without sufficient justification.

Disputes frequently turn on how courts define the classification and assess governmental interests.

Yes. Some state equal-rights or equality provisions are interpreted more broadly than federal equal protection.

Advocates may choose state courts to obtain wider or faster protections.

Public opinion can affect which cases are brought, how governments defend laws, and how lower courts apply precedent.

It may also influence perceptions of legitimacy, even though constitutional rulings are not formally decided by polling.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks) Explain how the Equal Protection Clause can be used to support LGBTQ rights advocacy.

1 mark: Identifies that the Fourteenth Amendment requires states to treat people equally under the law.

1 mark: Links this to challenging state laws/policies that discriminate against LGBTQ people.

1 mark: Explains that courts can strike down unequal classifications lacking sufficient justification.

(4–6 marks) Assess the extent to which Supreme Court decisions have advanced LGBTQ rights through equal protection arguments.

1 mark: States a defensible judgement about impact (e.g., significant but contested/uneven).

2 marks: Uses accurate evidence from at least two relevant cases (e.g., Romer, Windsor, Obergefell) showing how unequal treatment was addressed.

1 mark: Explains how equal protection reasoning supported movement goals (e.g., invalidating discriminatory classifications).

1–2 marks: Develops a limitation or counterpoint (e.g., scrutiny disputes, continued legal/political conflict, uneven protections).