AP Syllabus focus:

‘Interpreting the free exercise clause involves deciding when individuals may practice religion freely and when laws may restrict conduct.’

The Free Exercise Clause protects religious practice from improper government interference, but it is not unlimited. Courts continually weigh individual conscience against the government’s interest in enforcing generally applicable laws.

Core idea: protecting religion, permitting regulation

The First Amendment bars government from prohibiting the free exercise of religion. In practice, conflicts usually arise when a law regulates conduct that a person claims is religiously required (or forbidden).

Belief vs. conduct

Courts have long drawn a distinction between:

Religious belief (strongly protected)

Religiously motivated conduct (can be regulated in some circumstances)

In Reynolds v. United States (1879), the Court upheld a federal ban on polygamy, reasoning that allowing religious duty to override criminal law would make each person “a law unto himself.”

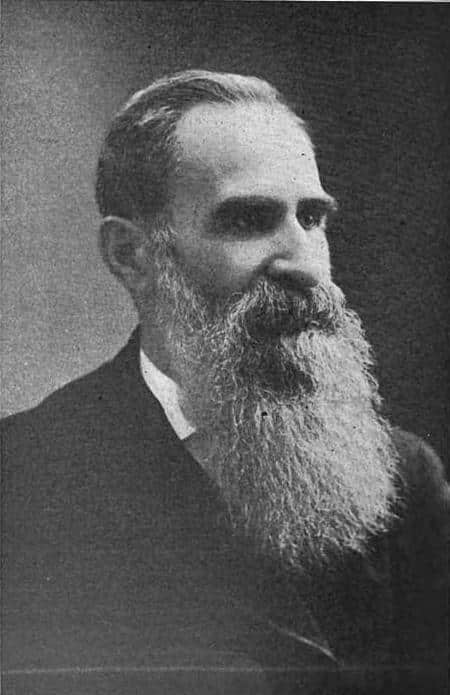

A news photograph accompanying an explanation of Reynolds v. United States (1879), the early Supreme Court case that helped cement the belief–action distinction in free-exercise doctrine. It illustrates the core idea that government generally may not regulate religious belief, but may regulate conduct—even if religiously motivated—when it conflicts with criminal law or public order. Source

Legal standards the Court uses

The key constitutional question is whether government is regulating religion itself or regulating conduct through a broader rule.

Neutral law of general applicability: a law that does not target religion and applies broadly to comparable conduct, regardless of religious motivation.

When laws burden religion: competing approaches

Historically, the Court sometimes required strong justification for burdens on religious practice:

Sherbert v. Verner (1963): denial of unemployment benefits to a Seventh-day Adventist who refused Saturday work was unconstitutional; the Court applied a demanding test.

Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972): Amish parents received an exemption from compulsory schooling past eighth grade.

Later, the Court narrowed constitutionally required exemptions:

Employment Division v. Smith (1990): Oregon could deny unemployment benefits to employees fired for using peyote, even if used religiously, because the drug law was neutral and generally applicable. After Smith, the Constitution typically does not require religious exemptions from such laws.

A separate sentence between definition blocks is required, and the practical impact of Smith is that many disputes shift to whether a law is truly neutral and generally applicable, or whether political processes (or statutes) create exemptions.

Strict scrutiny: the highest level of judicial review requiring the government to prove a compelling interest and that the law is narrowly tailored (uses the least restrictive means) when it substantially burdens a protected right.

Targeting religion triggers tougher review

Even after Smith, government may not single out religious practice:

Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. Hialeah (1993): city ordinances aimed at Santería animal sacrifice were struck down because they targeted a specific religious practice (not neutral, not generally applicable).

Statutory protections and limits (policy choices)

Because Smith reduced constitutionally required exemptions, Congress and states have sometimes expanded protection by statute.

President Bill Clinton signs the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) at the White House (November 16, 1993). The image connects the Supreme Court’s post-Smith free-exercise framework to Congress’s statutory decision to require strict scrutiny for certain federal burdens on religious exercise. Source

Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA, 1993) (federal): generally requires strict scrutiny when the federal government substantially burdens religious exercise.

City of Boerne v. Flores (1997): limited RFRA’s reach against state governments (it still applies to the federal government).

Under RFRA, the Court has sometimes required accommodations:

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014): closely held corporations could claim RFRA protection against certain federal contraceptive-coverage requirements, where less restrictive alternatives existed.

Common tensions the Court must balance

Disputes often turn on:

Whether the law is neutral or effectively hostile to religion

Whether religious claimants seek an exemption that would undermine a broader regulatory system

Whether accommodating religion would shift burdens to others (e.g., employees, consumers, or the public)

FAQ

No. After Smith, exemptions are not generally required when a law is neutral and applies broadly.

Exemptions may still arise if a law targets religion or via legislation.

They look at text, purpose, and implementation.

Evidence can include unusual carve-outs, selective enforcement, or statements showing hostility to religion.

Yes, particularly when rules apply across the board.

Disputes usually focus on whether the rule is applied equally to comparable secular conduct.

Courts may be wary if an exemption would seriously undermine a regulatory scheme or impose significant costs/harms on others.

They assess practical effects, not just sincerity.

Sometimes, particularly under statutes like RFRA for federal actions.

Courts assess the legal form (e.g., closely held firms), the nature of the burden, and whether less restrictive alternatives exist.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain what the Free Exercise Clause protects, and identify one limit on that protection.

1 mark: Identifies that the Free Exercise Clause protects individuals’ religious practice/worship from government interference.

1 mark: States a valid limit (e.g., religiously motivated conduct can be regulated; neutral, generally applicable laws may be enforced; government may restrict conduct for public order/safety).

(6 marks) Using Supreme Court reasoning, analyse how the Court decides whether a government law that burdens religious conduct is constitutional. Refer to at least one relevant case.

1 mark: Explains that the key issue is whether the law is neutral and generally applicable or targets religion.

1 mark: Accurate use of Employment Division v. Smith (neutral, generally applicable laws usually upheld even if they burden religion).

1 mark: Accurate use of Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. Hialeah (laws targeting religion struck down).

1 mark: Explains heightened scrutiny/strict scrutiny when targeting or when required by statute (e.g., RFRA for federal action).

1 mark: Applies reasoning to burdens on conduct (belief vs conduct distinction).

1 mark: Coherent analysis of balancing religious liberty with governmental interests (e.g., enforcement, public order).