AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Supreme Court has held that speech—including symbolic, nonverbal actions communicating ideas—is protected by the First Amendment.’

The First Amendment protects more than spoken or written words. Supreme Court doctrine treats many forms of expression as “speech,” while also recognising categories and contexts where government may regulate expression without violating constitutional liberty.

Core idea: what counts as “speech”

The First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech covers expressive activity intended to communicate ideas to others. Courts ask whether the activity is sufficiently communicative to trigger constitutional scrutiny.

Symbolic speech: Nonverbal conduct that is intended to convey a message and is likely to be understood by observers (for example, wearing armbands, burning a flag, or other expressive acts).

Symbolic expression matters in practice because many political messages are conveyed through protest tactics, clothing, art, or refusal to comply with certain expressive demands.

Protected vs. unprotected expression (high-level)

Not every communicative act receives the same constitutional shelter. For this subtopic, the key distinction is that many nonverbal actions are protected as speech, so the government must justify restrictions with stronger reasons than mere disagreement with the message.

How the Court evaluates symbolic speech claims

When someone argues that the government punished them for expression, courts typically separate two questions: (1) is the conduct expressive enough to be “speech”? and (2) is the government regulating the message or regulating conduct for some other reason?

Step 1: Is the conduct expressive?

Courts look for:

Intent to communicate (the actor meant to express an idea)

Likelihood of understanding (viewers would probably recognise a message in context)

If these are present, the First Amendment is usually triggered even without words.

Step 2: What is the government’s reason?

A central line is between:

Content-based regulation: the law targets the idea, viewpoint, or message being expressed

Content-neutral regulation: the law targets non-communicative aspects of conduct (for example, safety risks), even though expression is incidentally burdened

Symbolic speech disputes often hinge on whether the government is truly addressing a non-speech problem or is using a conduct rule as a proxy to suppress an unpopular message.

Landmark cases that illustrate protected symbolic speech

These cases are commonly used to show that the Court treats certain nonverbal actions as constitutionally protected expression.

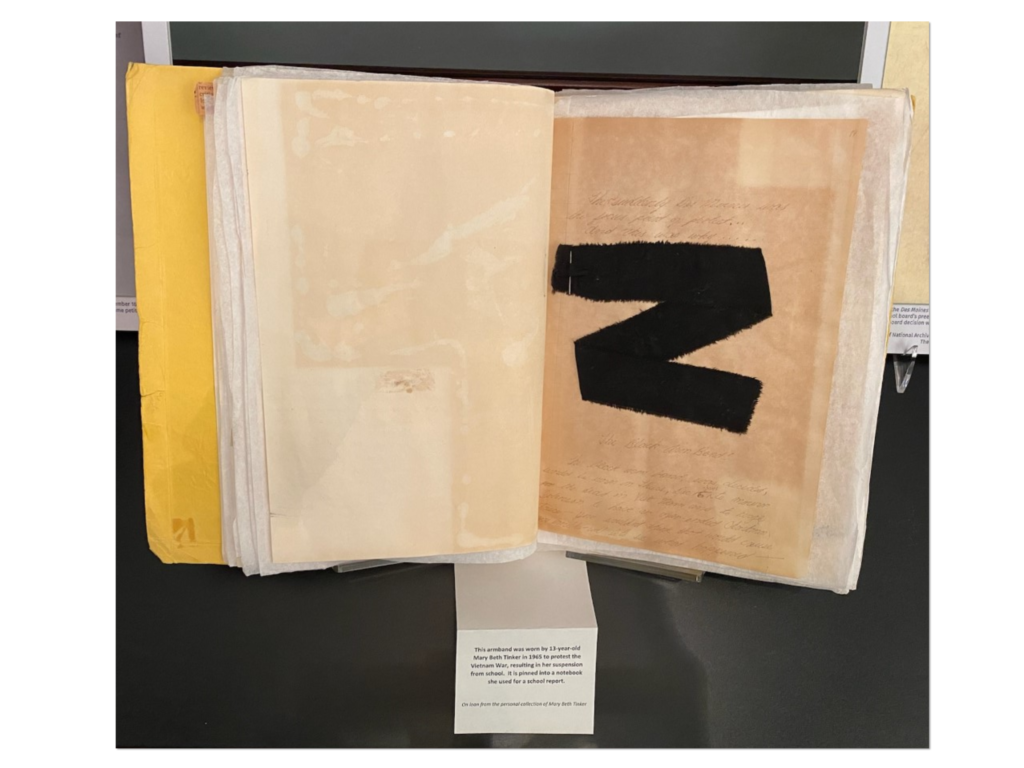

Tinker v. Des Moines (1969): student armbands

A photo of Mary Beth Tinker’s original black armband displayed as a historical artifact, reinforcing that clothing and other nonverbal acts can function as political expression. The exhibit context helps students connect the concrete protest tactic (the armband) to the constitutional principle that students retain First Amendment rights at school, subject to specific limits. Source

The Court protected students wearing black armbands to protest war, emphasising that students do not “shed their constitutional rights” at school. The armbands were treated as symbolic political speech, and the school needed more than discomfort or controversy to justify punishment.

Texas v. Johnson (1989): flag burning

A photograph of the U.S. flag being burned, illustrating the kind of expressive conduct at issue in Texas v. Johnson (1989). In that case, the Court treated flag burning in political protest as symbolic speech and emphasized that punishing the act because of the message it conveys is a content-based restriction. Source

The Court held that burning the American flag in political protest is protected expression. The state’s interest in preserving the flag as a symbol could not justify punishing a particular political message; the restriction was effectively content-based.

United States v. O’Brien (1968): expressive conduct can still be regulated

Burning a draft card had expressive elements, but the Court upheld the conviction because the law served important governmental interests unrelated to suppressing expression (maintaining the draft system). This illustrates a key limit: symbolic conduct can be regulated when the government is addressing a legitimate non-speech concern and the rule is not aimed at the message.

Key takeaways for AP Government analysis

When analysing a protected or symbolic speech claim, focus on the constitutional logic the Court uses:

Identify the expressive conduct and the message it communicates.

Ask whether the government’s rule targets the message or targets conduct for independent reasons.

Use case analogies: armbands (protected), flag burning (protected), draft card burning (regulation upheld due to non-speech interest).

Keep the syllabus emphasis in view: the Court has repeatedly recognised that speech includes symbolic, nonverbal actions communicating ideas, bringing such conduct within the First Amendment’s protection.

FAQ

Courts look to context: the setting, audience, and common social meaning of the act.

They may consider whether similar conduct is widely recognised as protest (e.g., kneeling, wearing a symbol) and whether the actor’s purpose was communicative.

Content discrimination targets a subject matter (e.g., banning all anti-war symbols).

Viewpoint discrimination targets a particular side of a debate (e.g., banning only anti-war symbols but allowing pro-war symbols), and is treated as especially constitutionally suspect.

Compelled expression issues arise when law requires an individual to display, say, a slogan or symbol.

Courts scrutinise whether the requirement forces endorsement of an ideological message, rather than merely regulating routine, non-ideological conduct.

O’Brien shows that protection is not absolute when conduct is intertwined with expression.

A law may survive if it serves an important interest unrelated to suppressing expression and burdens speech no more than necessary to achieve that interest.

Often, First Amendment limits apply to government action, not private owners.

Some states interpret their own constitutions to provide broader access rights, but federally the key question is typically whether there is “state action” involved.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain what is meant by “symbolic speech” under the First Amendment.

1 mark: Defines symbolic speech as nonverbal conduct intended to convey a message.

1 mark: Adds that the message is likely to be understood by observers / treated as speech by the Supreme Court.

(6 marks) Using Supreme Court reasoning, assess whether punishing a protester for burning a national symbol is more likely to violate the First Amendment than punishing someone for destroying a government-issued document required for an administrative system.

1 mark: Identifies burning a national symbol as potential symbolic political expression.

1 mark: Uses Texas v. Johnson to support that punishing flag burning is unconstitutional when aimed at suppressing the message (content-based).

1 mark: Identifies destruction of a required government document as conduct with administrative implications.

1 mark: Uses United States v. O’Brien to explain regulation may be upheld when the government interest is unrelated to suppressing expression.

1 mark: Distinguishes content-based suppression from content-neutral regulation of conduct.

1 mark: Reaches a comparative judgement consistent with the above reasoning.