AP Syllabus focus:

‘Supreme Court decisions on the Second Amendment depend on how the justices interpret the constitutional right to bear arms.’

Interpreting the Second Amendment starts with careful reading of its grammar, punctuation, and eighteenth-century word meanings. Justices then choose interpretive methods that determine how much weight to give each clause of the text.

The Text to Be Interpreted

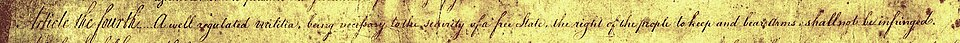

The Second Amendment reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Cropped, high-resolution image of the Second Amendment as it appears on the Bill of Rights parchment. Seeing the original punctuation and continuous sentence structure helps explain why judges and scholars debate how the prefatory and operative clauses relate. This image supports close-reading arguments centered on grammar and textual structure. Source

Two Clauses, One Sentence

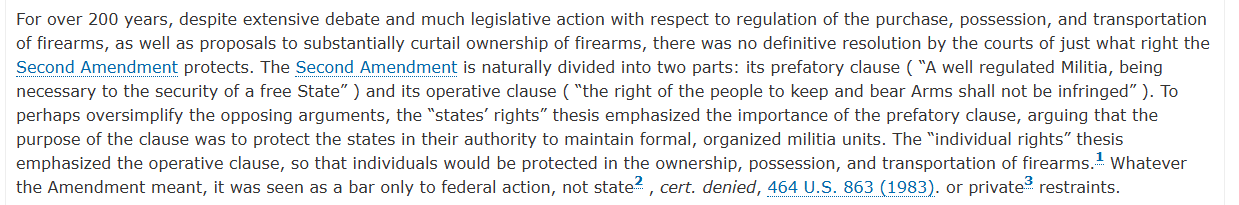

The amendment is commonly parsed into two parts that structure textual arguments.

Prefatory clause: Introductory language stating a purpose or rationale (here, “A well regulated Militia…”).

Operative clause: The language that states the legal rule (here, “the right of the people…shall not be infringed”).

Because both clauses appear in a single sentence, disputes often turn on whether the prefatory clause limits the operative clause, or instead explains one important reason for protecting it.

Explanatory reference page from the U.S. Constitution Annotated discussing Second Amendment doctrine, including the common division into a prefatory clause and an operative clause. This pairs well with the notes’ definitions by showing how courts and legal commentators use the clause framework in real constitutional analysis. It helps students connect grammatical structure to doctrinal disputes over individual-right versus militia-centered readings. Source

Key Words and Phrases That Drive Interpretation

“The right of the people”

Text-focused analysis compares “the people” across the Bill of Rights (e.g., First and Fourth Amendments) to infer whether the phrase signals an individual right, a collective right tied to civic functions, or a right held broadly but exercised within regulated contexts. The textual hook is consistency: if the same phrase is used elsewhere, is it presumed to carry a similar meaning here?

“Keep and bear Arms”

Interpreters separate two verbs:

“keep”: to possess or have.

“bear”: to carry.

They also analyse whether “bear Arms” was an idiom with a primarily military sense or a broader carrying sense, and whether “Arms” should be read narrowly (weapons associated with militia service) or more generally (weapons commonly possessed).

“Well regulated Militia” and “security of a free State”

The phrase “well regulated” is examined for period-appropriate meaning (often argued as “well trained,” “well functioning,” or “properly disciplined,” rather than “heavily restricted” in the modern administrative sense). “Militia” is read alongside founding-era practice in which militias were drawn from the populace. Textually, this supports competing readings: either the amendment’s scope is anchored to militia-related purposes, or it presumes an armed populace as a condition of collective security.

Methods Justices Use to Read the Text

Textualism and grammatical analysis

Textualism emphasises the ordinary public meaning of the words at the time of ratification, as reflected in usage, syntax, and structure.

Textualism: An interpretive approach that prioritises the Constitution’s public meaning as conveyed by its words and grammar, rather than later policy goals.

Textualists often argue that clause structure matters: if the operative clause is grammatically complete, it can be treated as announcing a right that is not exhaustively defined by the prefatory clause.

Original public meaning and historical usage

Even when focusing “on the text,” justices consult founding-era dictionaries, legal sources, and common usage to decide what disputed terms meant when adopted. This is not the same as asking what specific framers privately intended; it is a claim about how a reasonable reader at the time would have understood the words.

Canonical arguments (rules of reading)

Courts sometimes apply general interpretive presumptions, such as:

avoiding readings that make words superfluous (every clause should do work if possible)

reading the text as a coherent whole (the purpose clause and rights clause should fit together)

resisting interpretations that rewrite terms to match modern preferences (the judge’s role is interpretation, not amendment)

Why Textual Interpretation Produces Different Outcomes

The Second Amendment contains broad rights language (“shall not be infringed”) alongside context-setting language (militia and security). Different interpretive choices—how tightly to link the clauses, how to translate eighteenth-century usage into modern doctrine, and how broadly to read “Arms”—shape what regulations are seen as consistent with the constitutional text.

FAQ

Potentially. Eighteenth-century punctuation was less standardised, so justices may treat commas as helpful but not decisive. The bigger issue is whether the sentence remains grammatically complete without the prefatory clause and how the clauses logically relate.

Typically: founding-era dictionaries, legal treatises, contemporaneous newspapers/pamphlets, and early governmental practice. The goal is usage evidence, not personal intentions of particular framers.

Because repeated constitutional phrases can imply a consistent referent. Comparing the First, Second, and Fourth Amendments is a way to argue that “the people” signals a similar type of right-holder across the Bill of Rights.

Textually, it supplies context for why the amendment was adopted (“necessary to the security of a free State”). Disputes arise over whether that context defines the full scope of the right or merely provides a prominent justification.

By focusing on period usage. Many historical readings emphasise functional competence (trained, disciplined, effective). The interpretive move is to translate the phrase as it was publicly understood at ratification, rather than as a modern regulatory slogan.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Explain how the prefatory clause could affect interpretation of the operative clause in the Second Amendment.

1 mark: Identifies the prefatory clause as stating a purpose/rationale about a “well regulated Militia”.

1 mark: Identifies the operative clause as the rule protecting “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms”.

1 mark: Explains linkage: prefatory clause may be read as informing/limiting the scope of the right, or as merely explaining one reason for protecting it.

(6 marks) Assess how a textualist approach might interpret the phrases “the people” and “bear Arms,” and why those interpretations could lead to different constitutional conclusions.

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes textualism as focusing on the public meaning of the text’s words/grammar.

2 marks: “the people” analysis (any two): comparison with other amendments; individual-versus-collective implications; inference from consistent phrasing.

2 marks: “bear Arms” analysis (any two): carry versus military idiom; pairing with “keep”; scope of “Arms”.

1 mark: Links differing readings to differing legal conclusions about the breadth of the protected right.