AP Syllabus focus:

‘Even when officials cite national security, the Court has bolstered press freedom and generally resists prior restraints.’

The First Amendment’s press clause often collides with government claims that secrecy is necessary for security. Supreme Court doctrine generally protects publication and treats censorship before publication as constitutionally suspect.

The constitutional issue: press freedom vs. secrecy

What the government argues

When officials invoke national security, they typically claim that publication will:

reveal military plans, intelligence sources, or operational methods

endanger troops, inform adversaries, or damage diplomacy

undermine the government’s capacity to conduct foreign affairs

These arguments are often used to justify blocking publication, not merely punishing unlawful conduct after the fact.

What the press argues

The press typically emphasises that:

the First Amendment protects newsgathering and publication on matters of public concern

public oversight of war, surveillance, and diplomacy requires information that governments may prefer to withhold

allowing security claims to silence reporting can enable abuse, error, and deception

Prior restraint is the central battlefield

Government efforts to stop publication in advance are called prior restraints, and they receive the most hostile treatment from the Court.

Exterior view of the United States Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., the institution that evaluates whether government attempts to block publication qualify as unconstitutional prior restraints. In AP Gov terms, this image reinforces that prior-restraint fights are typically resolved through judicial review of executive justifications and evidentiary showings. Source

Prior restraint: a government action (law, court order, or licensing scheme) that blocks speech or publication before it occurs.

A key idea for AP Gov is the Court’s strong presumption that prior restraints are unconstitutional, especially when justified by broad, speculative security concerns rather than concrete, imminent harm.

The Pentagon Papers principle (New York Times Co. v. United States, 1971)

Core holding

In the Pentagon Papers case, the federal government sought injunctions to stop major newspapers from publishing classified material about U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

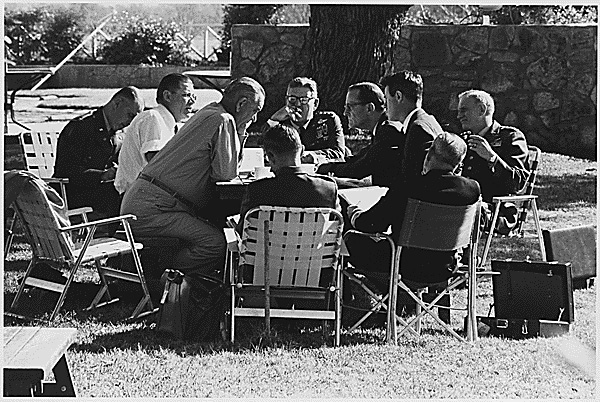

National Archives photograph of senior military leadership (the Joint Chiefs of Staff) meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the LBJ Ranch in 1964. The image helps contextualize the Vietnam-policy and national-security decision-making that the Pentagon Papers documented, which the government later argued required secrecy. Source

The Supreme Court refused to allow the injunctions, reinforcing that:

even urgent claims of national security do not automatically override the First Amendment

the government bears a heavy burden to justify stopping publication

Why the decision matters for this subsubtopic

The case illustrates the syllabus point directly: even when officials cite national security, the Court has bolstered press freedom and generally resists prior restraints. The ruling signals that “national security” is not a magic phrase that dissolves constitutional scrutiny; courts demand strong, specific proof.

Limits of what the case guarantees

The Pentagon Papers decision does not mean:

the press has a blanket right to obtain classified information by illegal means

the government can never punish leaks through other legal routes

all national-security-related injunctions are impossible

Instead, the case stands for the idea that stopping publication in advance is extraordinary and rarely permissible.

How courts think about national security claims

The government’s burden

When seeking censorship before publication, the government generally must show more than embarrassment or political damage. Courts look for:

specificity (what exact harm, from what exact disclosure)

immediacy (harm that is imminent rather than speculative)

directness (a clear causal link between publication and harm)

Institutional concerns

Courts are wary because:

executive officials have incentives to over-classify and overclaim danger

judges lack perfect information but can still require evidence, not slogans

allowing easy restraints can chill investigative reporting on powerful institutions

Practical implications for press freedom

What journalists can take from the doctrine

Publishing truthful information on matters of public concern receives robust constitutional protection.

Efforts to block publication using broad security rationales are usually constitutionally vulnerable.

The legal risk often shifts from “can we publish?” to “how was the information obtained, and what laws govern leakers?”

What government can still do

Even with strong protection against prior restraints, government may:

classify information and restrict access for employees/contractors

prosecute unauthorised disclosure by insiders under applicable statutes

argue for narrow, evidence-based restrictions in exceptional cases (though success is rare)

FAQ

Yes, in theory, but the threshold is extremely high.

A successful restraint would likely require highly specific, imminent, and severe harm, supported by concrete evidence rather than general assertions.

Classification is an executive label, not automatic proof of constitutional necessity.

Courts may treat classification as relevant, but still ask whether the government has demonstrated a real, immediate danger from publication.

Sometimes, depending on the law used and the facts.

Post-publication penalties raise different constitutional questions (and may still face serious First Amendment obstacles), but they are not the same as prior restraint.

It can increase scepticism because it suggests officials may use “security” to avoid embarrassment or accountability.

Judges therefore look for specificity and credible proof, not merely the presence of a classification stamp.

They can.

In disputes over subpoenas and confidential sources, the government may argue security needs justify compelled disclosure, creating a separate press-freedom conflict from prior restraint.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain why the Supreme Court is generally sceptical of prior restraints, even when the government claims national security.

1 mark: Identifies that prior restraint stops publication before it occurs and is strongly disfavoured under the First Amendment.

1 mark: Explains that national security claims must meet a heavy evidential burden; broad or speculative harms are usually insufficient.

(5 marks) Using New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), analyse how the Court balances national security claims against freedom of the press.

1 mark: Correctly identifies the case context (government sought to stop publication of classified Pentagon Papers).

2 marks: Explains the Court’s reasoning/standard (heavy burden; strong presumption against prior restraint; refused injunction).

1 mark: Connects to balancing (press oversight and public interest vs asserted security harm; security claim not automatically controlling).

1 mark: Notes a limitation/nuance (decision does not grant absolute right to obtain secrets or bar all post-publication consequences).