AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Supreme Court attempts to balance individual freedom claims with laws and enforcement procedures aimed at public order and safety.’

Individual rights are not unlimited. In civil liberties disputes, courts weigh constitutional protections against government claims that limits are necessary to prevent harm, maintain order, and protect the public.

The core constitutional problem: rights vs. regulation

The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment protect individual liberty, but government also has a duty to provide public safety. Many cases arise when laws or enforcement practices burden a right in the name of security (for example, protests, policing tactics, or emergency restrictions).

Why “balancing” happens

Courts balance because:

Rights can conflict with other rights and with community safety.

Government actions vary in severity (minor inconvenience vs. criminal penalties).

Threat levels differ (ordinary conditions vs. heightened risk situations).

How the Supreme Court structures the balance

Rather than treating every conflict as purely political, courts use predictable legal standards that ask (1) what right is involved, (2) how severely it is burdened, and (3) how strong the government’s justification is.

Levels of scrutiny (equal protection and some rights cases)

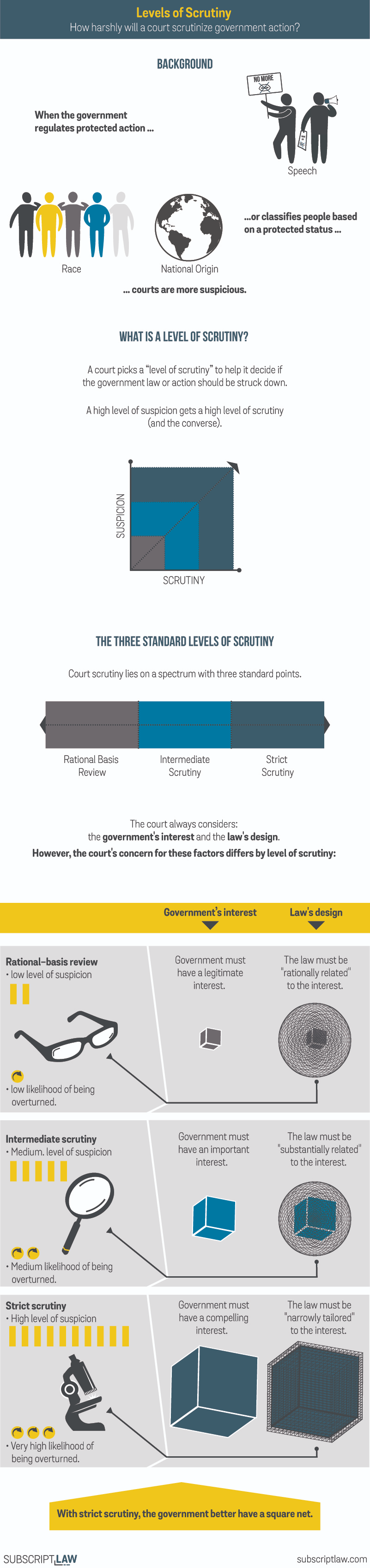

Diagram showing the three standard levels of scrutiny on a spectrum (rational basis → intermediate → strict) and how the government’s required justification and tailoring increase as courts become more skeptical. It reinforces the idea that higher scrutiny corresponds to a heavier burden on the government and a tighter means–ends fit. Source

Strict scrutiny: The toughest judicial test; the government must prove a law is narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest.

Strict scrutiny is commonly associated with laws that target certain classifications or heavily burden fundamental rights, so it strongly protects liberty unless the public-safety rationale is exceptionally strong.

Intermediate scrutiny: A mid-level test; the government must show a law is substantially related to an important interest.

Intermediate scrutiny reflects a compromise approach: the Court recognises meaningful government interests while still requiring real evidence and a close fit.

Rational basis review: The most deferential test; the law must be rationally related to a legitimate interest.

Rational basis typically gives government wide room to regulate for order and safety, so challengers usually lose unless the policy is arbitrary or irrational.

Reasonableness approaches (especially enforcement)

In many public-safety settings, the Court asks whether government conduct is reasonable under the circumstances. This framing often appears when evaluating policing and administrative practices, because officials must make rapid decisions and manage risk.

What factors influence outcomes

The Court’s balancing tends to turn on several recurring considerations.

The government’s interest and evidence

Judges look for:

The importance of the interest claimed (preventing violence is stronger than convenience).

The quality of evidence supporting the policy (real risk vs. speculation).

Whether the threat is immediate or remote.

Tailoring: how narrowly the policy limits liberty

Courts are more likely to uphold a safety measure when it:

Targets the specific harm rather than broadly restricting many people

Uses the least burdensome effective approach

Includes limits, oversight, or clear standards to reduce arbitrary enforcement

The severity of the burden on the individual

The Court informally weighs:

Whether the policy blocks the core of a right or merely regulates its exercise

Whether penalties are civil or criminal

Whether the measure affects vulnerable groups disproportionately

Common patterns in liberty–safety conflicts

Even without a single universal formula, several patterns are consistent across cases.

Rights are protected, but not absolute

A constitutional right can be subject to limits when government shows a sufficiently strong safety rationale and a close fit between means and ends. The harder the government hits a right, the stronger its justification must be.

Deference can increase in high-risk contexts

When officials claim heightened security needs, courts may grant more operational flexibility, especially where:

Decisions require expertise (threat assessment, security planning)

There is concern about second-guessing split-second judgments That said, deference is not unlimited; courts still police clear overreach or policies that lack meaningful constraints.

Courts worry about abuse and arbitrariness

Because “public safety” can be used as a broad justification, courts look for guardrails that protect liberty:

Clear rules to prevent discriminatory or viewpoint-based enforcement

Neutral criteria for restrictions

Opportunities for review (judicial or administrative)

Why this matters for AP Gov

Photograph of the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C., the institutional setting where constitutional balancing tests (like scrutiny and reasonableness) are applied. Using a real image of the Court’s seat helps connect abstract doctrinal frameworks to the actual decision-making body. Source

This balancing framework explains why Supreme Court decisions can shift over time: changes in perceived threats, evidence, and judicial philosophy affect how liberty claims are weighed against order and safety, even when constitutional text stays the same.

FAQ

Courts often look for evidentiary support and internal consistency.

They may weigh legislative findings, enforcement patterns, and whether the policy is applied neutrally across groups and viewpoints.

Common safeguards include:

Clear, objective standards for enforcement

Time limits and renewal requirements

Independent oversight or reporting

Meaningful avenues for review and complaint

Yes.

A court can view identical restrictions differently depending on the risk environment, available alternatives, and how directly the rule addresses the harm under the specific facts presented.

Different approaches prioritise different risks.

Some judges emphasise deference to elected branches on safety; others emphasise preventing rights erosion through overbroad rules and weak justifications.

Shifts can result from:

New factual records about risks and effectiveness

Changed social conditions and threat perceptions

Turnover in justices and evolving interpretations of what counts as “reasonable” or “compelling”

Practice Questions

Identify one way the Supreme Court balances individual liberty with public safety. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying a relevant method (e.g., applying a level of scrutiny; using a reasonableness test; requiring tailoring).

1 mark for a brief, accurate description of how it balances liberty and safety.

Explain how the strength of the government’s interest and the tailoring of a law can affect whether a rights-restricting policy is upheld by the Supreme Court. (5 marks)

1 mark for explaining that stronger interests (e.g., preventing serious harm) justify more restriction.

1 mark for explaining that weak/speculative interests undermine justification.

1 mark for explaining “narrow tailoring”/close fit to the stated safety goal.

1 mark for explaining that overbroad policies burden more liberty than necessary and are less likely to be upheld.

1 mark for linking these ideas to judicial tests (e.g., strict scrutiny requiring compelling interest + narrow tailoring, or reasonableness balancing).