AP Syllabus focus:

‘In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Court interpreted due process to protect privacy from government infringement.’

Griswold v. Connecticut is a foundational Supreme Court case that recognised a constitutional “right to privacy,” limiting state power to regulate intimate decisions within marriage through criminal law.

What the Case Was About

The Connecticut law and the challenge

Connecticut had a statute criminalising the use of contraceptives and assistance in obtaining them. Estelle Griswold (Planned Parenthood) and Dr C. Lee Buxton were convicted for providing contraceptive advice to married couples, creating a direct test case for constitutional review.

The constitutional problem the Court had to solve

The Constitution does not explicitly say “privacy.” The Court therefore had to decide whether due process protections could include a privacy right strong enough to invalidate the state’s contraception ban.

The Holding (What the Court Decided)

The Supreme Court struck down the Connecticut law, holding that it violated a constitutionally protected marital privacy.

Photograph of the U.S. Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., the institution that decided Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). Pairing the landmark holding with an image of the Court reinforces that constitutional rights here were defined through judicial review of a state criminal statute. Source

The key syllabus point is that the Court interpreted due process to protect privacy from government infringement, treating the statute as an unacceptable intrusion into an intimate, personal sphere.

How the Majority Reasoned: Privacy as an Implied Constitutional Right

Justice Douglas’s majority opinion argued that several Bill of Rights guarantees create “zones” of privacy that government may not invade without strong justification.

Unenumerated rights: Rights not explicitly listed in the Constitution but argued to be protected through constitutional structure, history, or interpretation.

Douglas described privacy as arising from the “penumbras” (shadows or implications) cast by multiple amendments, rather than from one explicit clause.

Penumbras: Implied protections inferred from the text and purpose of explicit constitutional guarantees, used to argue that broader rights flow from enumerated rights.

Amendments the Court linked to privacy

High-resolution scan of the U.S. Bill of Rights as preserved by the National Archives. This primary source visually anchors the “penumbras” discussion by showing the amendments the Griswold majority linked to implied privacy protections (including the Ninth Amendment’s unenumerated-rights language). Source

First Amendment: freedom of association implies space for private relationships and decisions.

Third Amendment: limits quartering of soldiers, reflecting a principle of home privacy.

Fourth Amendment: protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, signalling a boundary against state intrusion.

Fifth Amendment: self-incrimination protection supports a private realm the state cannot force open.

Ninth Amendment: suggests the people retain rights beyond those listed (not the majority’s main anchor, but relevant to the privacy claim).

The Role of Due Process (Why This Was Enforced Against a State)

Because Connecticut is a state, the case operated through the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, which the Court used to apply constitutional limits to state criminal law in this context.

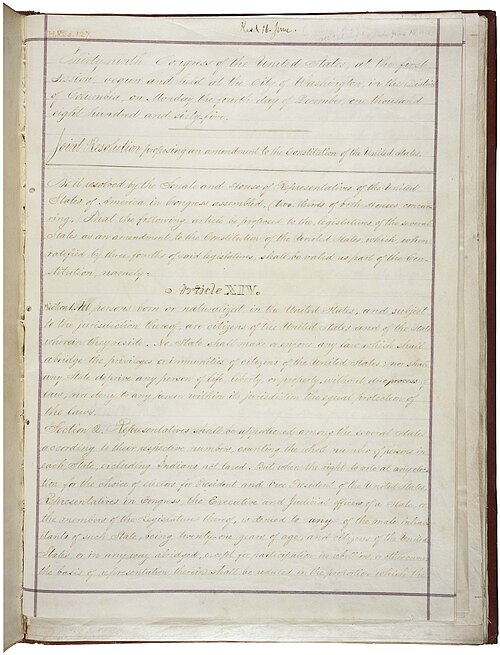

High-resolution scan of the Fourteenth Amendment (page 1), the constitutional vehicle for applying many rights against state governments through the Due Process Clause. In Griswold, the Court used this framework to treat “liberty” as broad enough to protect marital privacy against state criminal law. Source

Due process: Constitutional requirement that government must respect legal rights when depriving a person of life, liberty, or property; in some contexts it also protects certain fundamental liberties from undue government interference.

In Griswold, “liberty” was understood broadly enough to include a protected privacy interest in marital decisions about contraception, making the statute unconstitutional even if it applied to everyone.

Concurring and Dissenting Views (Why the Justices Disagreed)

Concurrences: different paths to the same result

Some justices emphasised the Ninth Amendment as evidence that rights exist beyond the enumerated list.

Others grounded the result more directly in Fourteenth Amendment liberty, treating privacy as a fundamental interest the state could not criminalise without a compelling reason.

Dissents: why some thought the law should stand

Dissenters argued the Connecticut law was unwise but not clearly prohibited by the Constitution’s text.

They warned that recognising privacy this way gave judges excessive power to identify rights not explicitly written into the document.

Why Griswold Matters for AP Government

It illustrates how the Court can expand civil liberties through interpretation, especially by reading due process as protecting substantive personal freedoms.

It provides a model for analysing how constitutional meaning can develop from text, structure, and precedent, not only explicit wording.

It highlights the continuing debate between broad constitutional interpretation (protecting implied liberties) and narrow interpretation (limiting courts to explicit text).

FAQ

It directly protected marital privacy against a state ban on contraceptive use and counselling, framing the issue as government intrusion into an intimate marital relationship.

The majority treated privacy as an implied freedom supported by several guarantees working together, making it harder to reduce privacy to a single clause.

Some justices cited it to argue that enumerating certain rights does not deny others retained by the people, supporting recognition of privacy as a retained right.

That the statute was foolish but not unconstitutional on the text, and that recognising implied privacy risks judges creating rights without clear constitutional authorisation.

Not by itself. The case signals heightened protection for intimate decisions, but the level of scrutiny depends on how later courts classify the interest and the regulation.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify the constitutional principle Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) used to protect marital privacy from a state law.

1 mark: Identifies the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause (or due process) as the vehicle.

1 mark: Links due process to protecting a right to privacy (marital privacy) against government infringement.

(5 marks) Explain how the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut reasoned that the Constitution protects a right to privacy, despite the word “privacy” not appearing in the text.

1 mark: Describes the Connecticut contraception law and the Court striking it down.

2 marks: Explains the “penumbras/zones of privacy” approach drawing implications from multiple amendments (credit any two, e.g., 1st/3rd/4th/5th/9th).

1 mark: Explains application against a state via the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause.

1 mark: Notes competing judicial approaches (e.g., Ninth Amendment emphasis or substantive liberty reasoning) or acknowledges dissent concerns about lack of explicit textual basis.