AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political socialization is the process through which individuals develop political beliefs, values, opinions, and behaviors.’

Political socialization explains how people come to see politics as meaningful (or not), learn what government is “for,” and decide how to act as citizens. It connects personal identity to public life and ongoing participation.

Meaning and Scope of Political Socialization

Political socialization: The lifelong process through which individuals develop political beliefs, values, opinions, and behaviors.

Political socialization is broader than simply learning facts about government. It includes learning:

Beliefs (what someone thinks is true about politics)

Values (what someone thinks ought to matter, such as liberty or equality)

Opinions (issue-specific preferences that can shift with events or information)

Behaviors (actions such as voting, protesting, donating, or disengaging)

It operates across a lifetime, but early learning is often “sticky” because basic orientations—like trust in government or comfort with political conflict—can become part of a person’s identity.

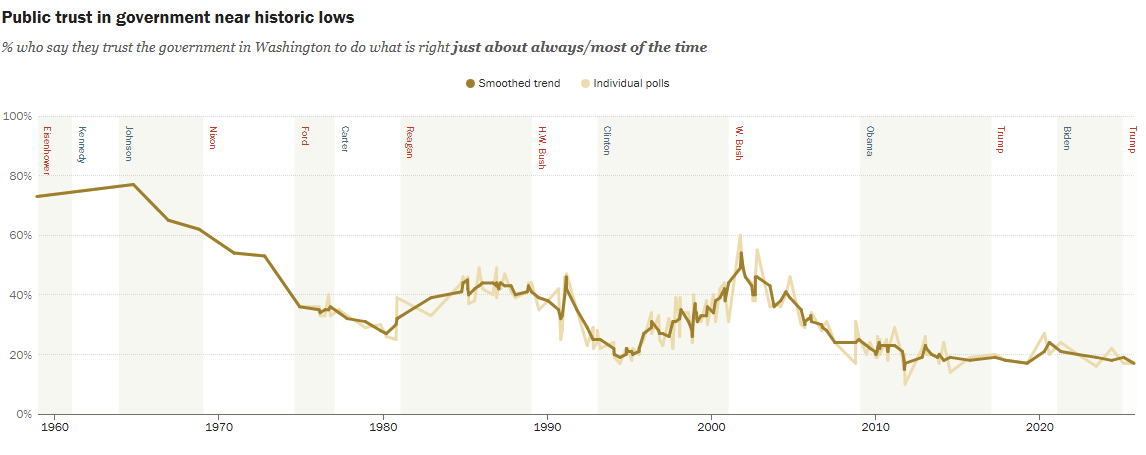

This time-series chart tracks Americans’ trust in the federal government from 1958 to 2025, showing large historical swings and a long-term decline to relatively low levels. It illustrates how legitimacy-related attitudes can be shaped by major national events and political context, while still exhibiting durable patterns across decades. In study terms, it is a clear example of an enduring orientation that can be reinforced or updated over time. Source

How the Process Works

Political socialization happens through repeated exposure to political cues and experiences. People interpret these cues through:

Cognitive shortcuts (using simple rules to judge complex politics)

Group attachments (seeing politics through membership in social groups)

Personal experiences (how policies and institutions affect daily life)

Learning mechanisms

Political learning often occurs through:

Observation and modelling: adopting attitudes seen as normal or rewarded in one’s environment.

Social rewards and sanctions: approval for “acceptable” opinions and disapproval for “unacceptable” ones.

Information filtering: selective attention to messages that fit existing beliefs, shaping what is remembered.

Habit formation: repeated civic actions (or non-action) becoming routine over time.

These mechanisms help explain why political beliefs can feel personal and emotionally charged, even when they concern distant institutions.

Stability, reinforcement, and change

Socialization is not a one-time event. It involves:

Reinforcement: new information is interpreted in ways that confirm existing values and identities.

Updating: opinions shift when people encounter strong new evidence, persuasive messaging, or lived experiences that conflict with prior beliefs.

Resocialization: major disruptions (new environments, crises, or turning points) can reshape political views more substantially.

Change is usually easier in opinions than in deep values, which tend to be more durable.

What Political Socialization Produces

Political socialization generates orientations that structure political life, including:

Political efficacy: beliefs about whether individuals can understand politics and influence government.

Legitimacy beliefs: whether institutions and leaders are seen as rightful and deserving of obedience.

Partisanship and ideological leanings: identities that guide issue positions and candidate evaluations.

Participation norms: expectations about whether “good citizens” should be active, attentive, or deferential.

Tolerance for disagreement: comfort with pluralism, protest, and compromise.

These outputs matter because they shape how citizens interpret campaigns, evaluate performance, and respond to conflict.

Why Political Socialization Matters

In a democracy, public policy and elections depend on citizen preferences and participation. Political socialization affects:

Voter turnout and engagement: whether people feel politics is accessible and worth attention.

Polarisation dynamics: strong identity-based learning can harden “us versus them” thinking.

Responsiveness: officials anticipate what socialised publics will reward or punish at the ballot box.

Civic cohesion: shared democratic commitments can stabilise institutions even during disagreement.

Understanding political socialization helps explain why different citizens can encounter the same political facts yet reach different conclusions about what government should do.

Studying Political Socialization

Researchers study political socialization by looking for patterns over time and across groups, using:

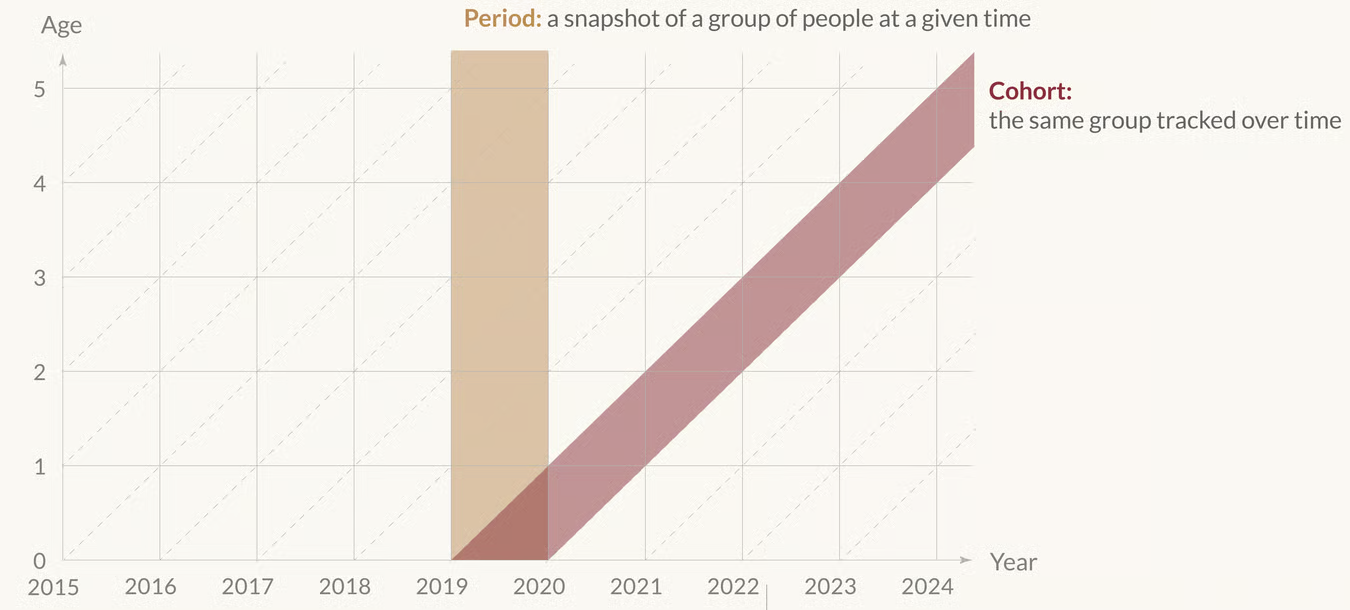

This diagram contrasts period data (different people measured at one point in time) with cohort data (the same group followed across time). It helps clarify why cohort comparisons and panel studies can reveal patterns of change that a single cross-sectional survey cannot capture. Methodologically, it reinforces that “change over time” depends on how the data are structured, not just what questions are asked. Source

Surveys to measure values, trust, efficacy, and participation.

Panel studies to track the same individuals as their opinions and behaviours evolve.

Cohort comparisons to see how people shaped in different eras differ as adults.

Qualitative evidence (interviews and life histories) to understand how individuals narrate political learning.

A key analytical challenge is separating enduring socialisation effects from short-term reactions, since political opinions can change quickly while underlying orientations change slowly.

FAQ

Yes. Many orientations form implicitly through routines, authority relationships, and social expectations.

Non-political settings can still teach what “rules” feel legitimate and who seems entitled to power.

Fact learning adds information (e.g., how a bill becomes law).

Socialisation shapes how you interpret facts—what you prioritise, trust, fear, or feel responsible to do.

They look for persistence over time using panel data.

Stable traits (trust, efficacy, identity) change more slowly than issue opinions, which can fluctuate with news cycles.

No. It can be deliberate (civic instruction) or accidental (unintended lessons from institutional experiences).

Unintentional cues can be powerful because they are repeated and normalised.

Attitudes tied to identity and core values are harder to shift.

Issue opinions are often more flexible because they depend on recent information and perceived personal impact.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define political socialisation and identify two types of outcomes it can produce in citizens.

1 mark: Accurate definition as a process through which individuals develop political beliefs/values/opinions/behaviours.

1 mark: Two valid outcomes identified (e.g., political efficacy, legitimacy beliefs, participation norms, partisanship).

(5 marks) Explain how political socialisation can produce both stability and change in citizens’ political behaviour over time.

1 mark: Explains reinforcement/habit or durable values leading to stability.

1 mark: Links stability to repeated cues/identity or information filtering.

1 mark: Explains updating/resocialisation as a pathway to change.

1 mark: Links change to new experiences/environments or persuasive information.

1 mark: Clearly connects these processes to behavioural outcomes (e.g., participation, engagement, voting).