AP Syllabus focus:

‘Family, schools, peers, media, and social environments—such as civic and religious organizations—help shape an individual’s political attitudes and values.’ """

Political beliefs do not develop in isolation. People learn what politics means, which issues matter, and how government should work through repeated exposure to influential groups, institutions, and information sources.

What “agents” do in political socialization

Agents of political socialization: The people, institutions, and contexts that transmit political beliefs, values, and behaviors to individuals over time.

Agents shape both political attitudes (views on specific issues, leaders, and events) and political values (more durable beliefs about what government should do and what a “good society” looks like). Their influence is often cumulative: early lessons create a baseline that later experiences reinforce or challenge.

Major agents named in the AP framework

Family

Family is often the earliest and most consistent source of political cues, especially before individuals have direct contact with politics.

Partisan leaning and ideology: Children may adopt a household’s general orientation (e.g., “government should help” vs. “government should stay limited”).

Political communication: Frequency of political discussion, conflict avoidance, or civic encouragement affects comfort with participation.

Social identity links: Family can connect politics to identity (religion, region, class, race/ethnicity), shaping which issues feel personally relevant.

Schools

Schools contribute through formal instruction and the “hidden curriculum” of norms and routines.

Civic education: Courses and activities teach basic structures (rights, elections, branches) and democratic expectations.

Norms of citizenship: Schools can promote political efficacy—the belief that one’s participation matters—through debate, student government, or service learning.

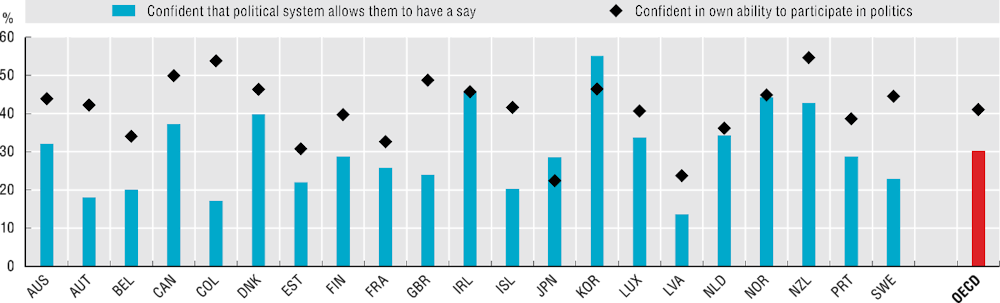

OECD cross-national chart separating internal political efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to participate/understand politics) from external political efficacy (belief that the political system gives people like you a say). The figure emphasizes that efficacy is multidimensional, helping explain why civic education can boost participation even when citizens still doubt government responsiveness. Source

Peer-moderated learning: Class discussions expose students to disagreement, compromise, and majority/minority dynamics.

Peers

Peers influence politics through social belonging and approval, especially in adolescence and early adulthood.

Photograph of a youth peer group used by OpenStax to illustrate how group norms and identity shape communication and self-presentation. In political socialization terms, the same dynamics can transmit “acceptable” opinions and participation habits by rewarding conformity and signaling belonging. Source

Social conformity pressures: People may adjust opinions to avoid conflict or maintain group membership.

Information shortcuts: Peer discussions often rely on simplified cues (party labels, slogans, “what people like us think”).

Participation habits: Friends can normalise voting, attending meetings, or activism by making it socially expected.

Media

Media supplies information, interpretations, and repeated narratives that can shape perceptions of reality.

Issue salience: Media attention can elevate which problems feel urgent, influencing attitudes about policy priorities.

Frames and interpretations: The way stories are presented can shape judgments about responsibility, fairness, and trust.

Fragmentation: A high-choice environment can sort audiences into different informational worlds, intensifying differences in attitudes and values.

Social environments (civic and religious organizations)

Organizations and community contexts link individuals to shared norms and collective action.

Civic organisations: Community groups, unions, and local associations teach participation skills (meeting norms, leadership, coalition-building) and can connect members to mobilising networks.

Religious organisations: Congregations may transmit moral frameworks that influence political values and issue positions, while also providing leadership cues and community pressure.

Local context: Neighbourhoods and workplaces expose individuals to prevailing community concerns, shaping what “normal” political opinions look like.

How multiple agents shape the same person

Political socialization is rarely one-directional; individuals experience overlapping influences.

Reinforcement: When family, peers, and community align, attitudes can become more stable and confident.

Cross-pressures: Conflicting cues (e.g., family partisanship vs. peer group views) can produce ambivalence, lower engagement, or more independent evaluation.

Timing matters: Early family influence can set a baseline, while later peer, media, and organisational experiences can reshape priorities and intensity of beliefs.

Why agents matter for political behaviour

Agents do more than form opinions; they help determine how a person engages with politics.

Participation: Social environments and peers can mobilise voting and volunteering by providing reminders, social rewards, and pathways to action.

Trust and legitimacy: Schools and media experiences can affect trust in institutions, perceived fairness, and willingness to accept outcomes.

Stability vs. change: Durable values often reflect long-term agent influence, while short-term attitudes may shift with new information environments and group memberships.

FAQ

Yes. Salient experiences (new peer group, workplace, congregation, media ecosystem) can weaken earlier cues, especially if reinforced daily.

They often teach participation skills and norms: meeting procedures, contacting officials, coalition-building, and a shared sense of community priorities.

Peers typically work through belonging and social approval, while family influence often comes from long-term modelling, identity links, and early exposure.

Personalised feeds can increase repetition of like-minded cues, speed up diffusion of narratives, and make peer signalling (likes/shares) part of opinion formation.

Often. Moral language, community expectations, and trusted leadership can shape underlying values that later map onto political attitudes and policy preferences.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Identify one agent of political socialisation and explain one way it can shape an individual’s political attitudes or values.

1 mark: Correctly identifies an agent (e.g., family, schools, peers, media, civic/religious organisations).

1 mark: Describes a plausible mechanism of influence (e.g., modelling, discussion, curriculum, group norms, framing).

1 mark: Links the mechanism to a political attitude or value (e.g., trust in government, issue preference, civic duty).

(6 marks) Analyse how TWO different agents of political socialisation can shape political attitudes and values. In your answer, compare the types of influence each agent is likely to have.

1 mark: Identifies first agent.

1 mark: Explains how the first agent shapes attitudes/values.

1 mark: Identifies second agent.

1 mark: Explains how the second agent shapes attitudes/values.

1 mark: Provides a valid comparison (e.g., early/continuous vs later/peer-driven; formal instruction vs informal norms; information supply vs identity reinforcement).

1 mark: Develops analysis by noting reinforcement or cross-pressure between agents.