AP Syllabus focus:

‘Generational effects—experiences shared by people of a common age—contribute to the development of a person’s political ideology.’

Generational effects help explain why groups raised under similar historical conditions often develop enduring political outlooks. In AP Gov, they are central to linking major events, shared experiences, and long-term patterns in ideology.

What “generational effects” mean

Generational effects argue that political beliefs are partly shaped by the distinctive environment people experience while “coming of age,” especially during highly visible national moments.

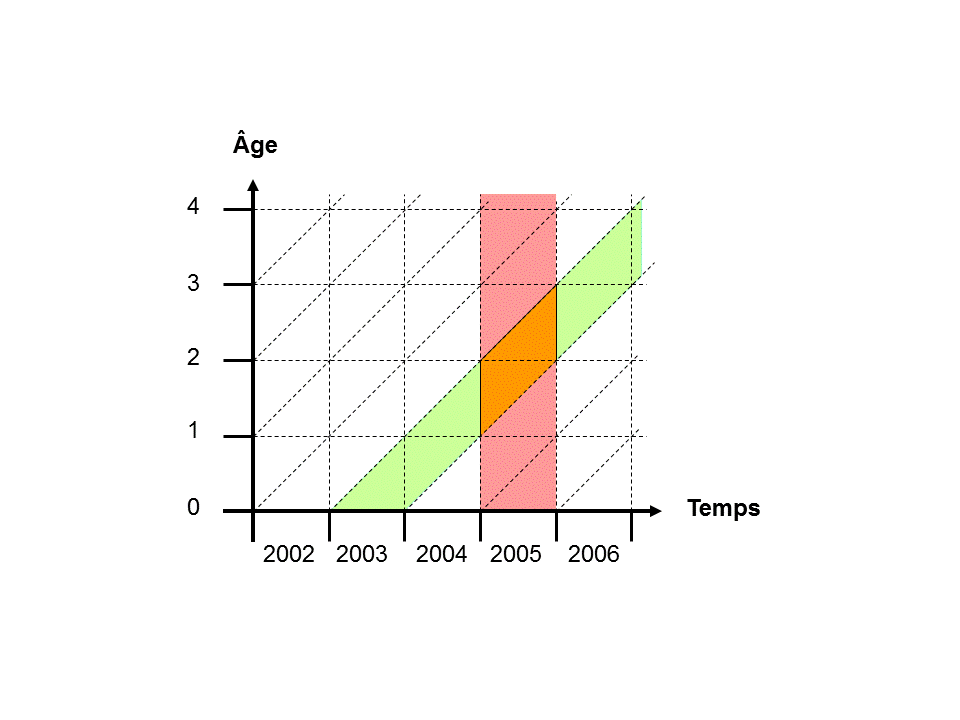

A Lexis diagram maps age (vertical axis) against calendar time (horizontal axis), making it easy to see how a birth cohort moves diagonally through time as it ages. Vertical slices represent period-wide events that affect many ages at once, while diagonal bands highlight cohort-specific exposure—useful for visualizing “generational effects” as distinct from broader national shocks. Source

Generational effects: The influence of shared experiences among people of a common age group on the development of political attitudes and, over time, political ideology.

These effects matter because early political learning can create a lasting “baseline” for how citizens interpret parties, leaders, and policy conflicts.

Political cohorts and shared context

A generational effect is usually discussed in terms of a political cohort—people who enter political awareness at roughly the same time and encounter similar political stimuli (media narratives, party coalitions, wars, economic conditions).

Political cohort: A group of people of similar age whose political attitudes are shaped by common formative experiences, producing identifiable patterns in ideology and partisanship.

Cohorts are not perfectly uniform; the key AP idea is that age-group patterns can be traced to shared political environments, not just individual choices.

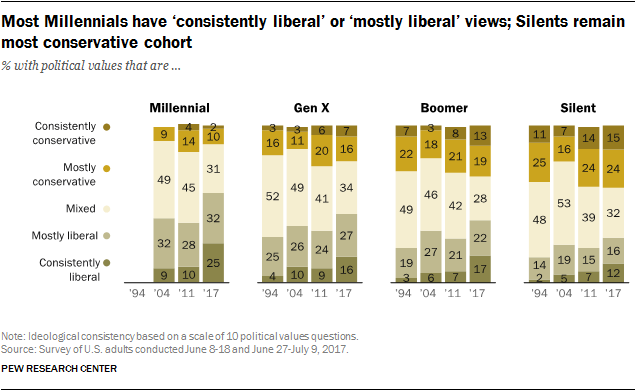

This stacked-bar chart compares the distribution of political values (consistently conservative → consistently liberal) across four generational cohorts at multiple time points. It illustrates how cohorts can maintain distinctive ideological profiles over time, which is the core empirical claim behind generational (cohort) effects in public opinion. Source

How shared experiences shape ideology

Generational effects tend to operate through a few recurring mechanisms that connect events to ideology.

1) Formative political learning

When citizens first pay attention to politics, they are learning:

what government is “for” (expectations of services, rights, and protections)

which party seems competent or trustworthy

which problems feel urgent or defining (security, inequality, inflation)

Because this learning happens during a sensitive period of identity formation, it can “anchor” later ideological labels such as liberal, conservative, or moderate.

2) Issue prioritisation and agenda imprinting

A cohort often carries forward the issues that dominated its formative years. This can influence ideology by:

making certain values feel non-negotiable (e.g., emphasis on order, equality, liberty, or tradition)

shaping which policy trade-offs feel acceptable (security vs. civil liberties; regulation vs. growth)

3) Party coalition impressions

Major elections and party realignments can produce cohort-level impressions of what each party “stands for.” Over time, this can affect:

partisan identification (long-term psychological attachment to a party)

ideological sorting (seeing one party as “my side” on core principles)

What counts as a “major shared experience” for a generation

For AP Gov purposes, generational effects are most clearly linked to widely experienced events and conditions, such as:

wars and international crises that redefine perceived threats and government responsibilities

economic booms or recessions that shape beliefs about markets, poverty, and government intervention

landmark social movements and cultural conflicts that redefine rights, identity, and national values

transformative changes in media and information (new platforms that change political engagement)

The event itself is less important than its visibility, duration, and perceived personal relevance to the cohort.

Limits and cautions when using generational effects

Generational explanations are powerful but not absolute. Be ready to qualify claims with these points:

Within-generation diversity: race, class, religion, region, and education can produce different ideological responses to the same event.

Unequal exposure: some groups experience policy outcomes (e.g., policing, healthcare access, tuition costs) more directly than others.

Period vs. cohort ambiguity: a national crisis can move many age groups at once; evidence for a true generational effect is strongest when the shift is distinctive and persistent within the cohort.

Measurement challenges: surveys may capture temporary reactions; durable generational effects show up as stable differences across repeated polling over time.

FAQ

They look for cohort differences that persist across repeated surveys. Strong evidence appears when the same birth cohort maintains distinctive attitudes as it ages, rather than converging quickly with other age groups.

Early adulthood is when many people first vote, build media habits, and adopt partisan identities. Attitudes formed then can become defaults, shaping how later information is interpreted.

Yes. Personal impact and group identity matter. The same event can increase trust in government for some while increasing scepticism for others, producing subgroup splits within the cohort.

Not necessarily. A cohort might instead develop issue-based ideology (e.g., strong civil-liberties commitments) without consistent loyalty to one party, especially if party positions shift.

Media environments affect what information is encountered, how politics is discussed, and which identities are reinforced. Cohorts socialised under different platforms can develop different trust levels and ideological cues.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks) Define “generational effects” and state one way they can influence political ideology.

1 mark: Defines generational effects as shared experiences among people of a common age shaping political beliefs/ideology.

1 mark: Links the concept to ideology (e.g., enduring liberal/conservative leanings, baseline attitudes).

1 mark: Gives one accurate mechanism (e.g., formative political learning, issue prioritisation, party impressions).

(4–6 marks) Explain how a major national event experienced during a cohort’s formative years can produce a lasting shift in that cohort’s ideology. Use two distinct explanatory steps.

1 mark: Identifies that formative years are a sensitive period for political learning.

2 marks: Step 1 explanation (e.g., event reshapes perceived role of government; changes core priorities such as security/equality).

2 marks: Step 2 explanation (e.g., cohort develops durable party/issue associations; reinforces ideological labels through repeated elections and discourse).

1 mark: Demonstrates “lasting” nature (e.g., persistence across time/polls; stable cohort pattern), not merely a short-term reaction.