AP Syllabus focus:

‘Life cycle effects—experiences people encounter at different life stages—also contribute to the development of political ideology.’

Life stage transitions can reshape what citizens need from government, which groups they identify with, and which issues feel most urgent. These shifting incentives and identities can gradually alter political ideology over time.

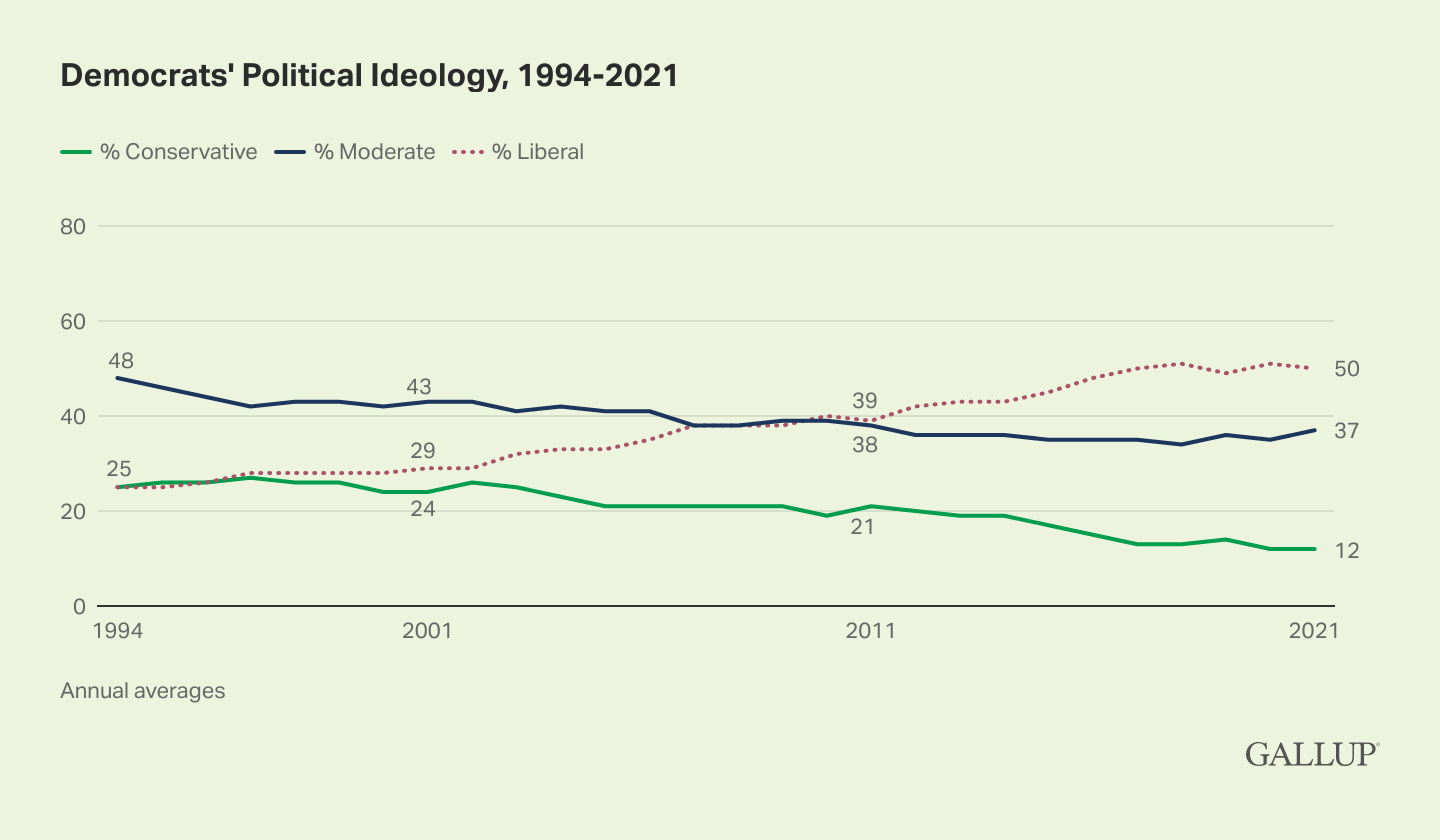

This line chart tracks the shares of Democrats identifying as conservative, moderate, or liberal from 1994 to 2021. The figure illustrates that ideological self-labels can move gradually over long periods, rather than changing instantly at a single life event. It is useful for connecting individual-level life transitions to broader, slow-moving shifts in political identity. Source

What “life cycle effects” means for ideology

Life cycle effects emphasize how ideology can change as people move through stages such as finishing school, starting work, forming families, buying homes, and retiring.

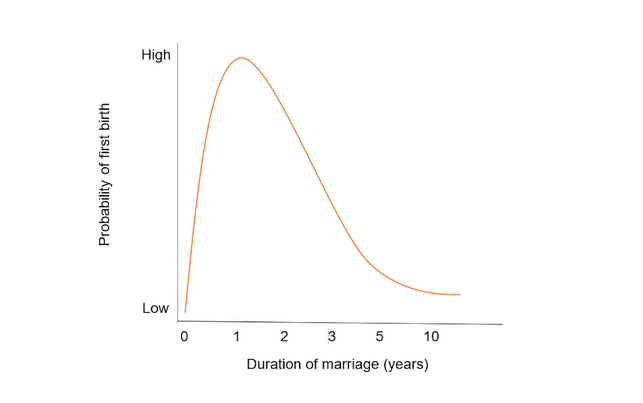

This figure models a life-course transition by plotting the probability of a first birth against the duration of first marriage. It demonstrates how transitions can be time-dependent and non-linear, a key intuition behind life-course approaches in political behavior and socialization. While the outcome here is demographic rather than ideological, the visual helps students grasp what scholars mean by “transitions” and “stages” shaping later attitudes. Source

The same individual may reinterpret core political debates differently as their responsibilities and risks change.

Life cycle effects: Changes in political attitudes and ideology associated with experiences and roles that commonly occur at different stages of an individual’s life (e.g., employment, parenthood, retirement).

These effects do not imply that everyone changes in the same direction; they highlight that life circumstances can create pressure to reassess political priorities.

How life stages can shift political ideology

Role changes and day-to-day incentives

As roles change, people may update their views on what government should do and who should pay for it.

Entering the workforce

Greater attention to wages, taxes, unions, health insurance, and workplace regulation

Stronger interest in government performance and economic management

Marriage, partnership, and caregiving

Increased concern with family policy, healthcare access, and community safety

More frequent trade-offs between individual freedom and social protection

Parenthood

Heightened salience of education policy, child health, and local public services

More interaction with government through schools and benefits systems, shaping trust and evaluations

Homeownership

Greater sensitivity to property taxes, zoning, interest rates, and neighborhood conditions

Potentially stronger preference for stability and predictability in public policy

Retirement and aging

Increased reliance on or attention to Social Security, Medicare, prescription drug policy

Greater focus on cost of living and service delivery rather than long-term wage growth

Economic security and risk tolerance

Life stages can change how people experience economic risk, which can reshape ideology about redistribution and regulation.

When income is uncertain (early career, job transitions), individuals may prefer stronger safety nets.

When assets and savings grow, individuals may prioritize tax policy and inflation control.

When fixed incomes matter (retirement), individuals may become highly attentive to price stability and benefit protection.

Social networks and identity cues

Life stages often reorganize social environments, which can reinforce or weaken ideological leanings.

New peer groups (workplaces, professional associations, parent networks) can normalise certain policy views.

Religious participation, neighborhood context, and civic involvement can shift with family and work demands, changing exposure to political messages.

Identity roles (e.g., “parent,” “veteran,” “small business owner”) can make certain issues feel personally consequential, encouraging ideological consistency around those interests.

What life cycle effects do (and do not) predict

Probabilistic, not automatic

Life cycle effects suggest tendencies, not rules.

Some people become more supportive of public spending when they use public schools or health programs.

Others become more skeptical of government as they encounter taxes, bureaucracy, or regulation.

Many remain ideologically stable but change issue priorities (what they care about most), which can still alter voting and participation.

Interaction with life circumstances

The same life stage can produce different ideological shifts depending on context.

Student debt, local housing costs, or childcare prices can push similar-aged citizens toward different conclusions about government responsibility.

Race, religion, region, gender, and socioeconomic status can shape how life events are interpreted politically.

A person’s earlier beliefs can filter later experiences, leading them to reinterpret events in ways that reinforce, rather than change, prior ideology.

Timing and “issue ownership” in personal life

Life cycle effects often appear as changes in which policies feel urgent.

Early adulthood: opportunity, education, jobs, civil liberties

Midlife: schooling quality, taxes, public safety, healthcare costs

Later life: retirement security, health coverage, cost of living, service access

These shifting priorities can move a person along ideological dimensions (economic or social), even without a complete partisan realignment.

FAQ

No. Some individuals shift towards greater support for social programmes with healthcare or retirement needs, while others prioritise lower taxes or limited regulation. The direction depends on resources, experiences, and local context.

They often use repeated surveys and statistical models to distinguish age-related role changes from period-specific shocks and cohort differences, but separation is imperfect because these influences overlap.

Common inflection points include entering stable employment, unemployment, marriage or caregiving, parenthood, homeownership, and retirement—especially when they change financial risk or dependence on public services.

Yes. Someone may keep the same ideological label yet place much greater weight on schooling, healthcare, or pensions as their circumstances change, affecting vote choice and participation.

Not always. Wealth can buffer risk and reduce reliance on public provision, while lower-income households may experience stronger policy stakes during transitions like job loss, childcare needs, or retirement insecurity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Define life cycle effects and explain one way a life stage transition could contribute to a change in political ideology.

1 mark: Correct definition of life cycle effects (changes in attitudes/ideology linked to experiences at different life stages).

1 mark: Identifies a valid life stage transition (e.g., entering workforce, becoming a parent, retirement, homeownership).

1 mark: Explains a plausible link to ideological change (e.g., shifting priorities about taxation, welfare, education, healthcare, regulation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) A citizen becomes a homeowner and later retires. Explain two ways these life cycle experiences could affect their political ideology, and evaluate one limitation of using life cycle effects to predict ideological change.

2 marks (1+1): Explains first mechanism linked to homeownership (e.g., stronger concern with property taxes/zoning/stability affecting preferences for government size or local policy).

2 marks (1+1): Explains second mechanism linked to retirement (e.g., increased salience of Social Security/Medicare/cost of living shaping views on public spending or benefit protection).

1–2 marks: Evaluates a limitation (e.g., effects are not uniform; prior beliefs filter experiences; socioeconomic context alters responses; people may shift issue salience without changing ideology).