AP Syllabus focus:

‘U.S. political culture—democratic ideals, principles, and core values—influences how public policy is formed, what goals it pursues, and how it is implemented over time.’

American public policy is not only a response to problems; it reflects shared beliefs about democracy, rights, and government. Those cultural commitments shape what policies seem legitimate, urgent, and workable across different eras.

Political culture as a driver of policy

Political culture supplies the “common sense” assumptions Americans bring to politics, influencing what government is expected to do, how much it should do, and which tools it should use.

Political culture: broadly shared beliefs, values, and norms about government, citizenship, and the meaning of democratic principles.

Political culture matters because policymakers anticipate public reactions and build coalitions within culturally acceptable boundaries. Even when parties disagree, they typically argue using culturally resonant language (for example, freedom, fairness, security, opportunity).

Democratic ideals, principles, and core values

U.S. political culture is often rooted in democratic ideals and core values that guide policy expectations over time, including:

Liberty: protecting individual rights and limiting arbitrary government power

Equality of opportunity: keeping pathways open for social and economic mobility

Popular sovereignty: government authority depends on public consent

Individualism: individuals are responsible for their choices and outcomes, within limits

Rule of law: predictable rules apply to citizens and leaders alike

These values do not automatically produce one “correct” policy; they structure the debate by setting standards for justification (for example, whether a policy protects rights, expands opportunity, or preserves accountability).

How political culture shapes policy formation

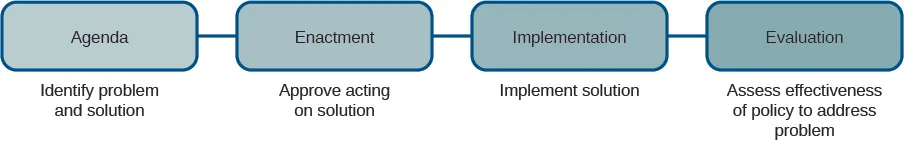

This diagram summarizes the public policy process as four connected stages: agenda setting, enactment, implementation, and evaluation. It helps clarify where political-culture pressures can enter—especially at agenda setting (what gets attention) and implementation (how rules are carried out). Source

Policy formation is shaped by cultural expectations about legitimacy, responsibility, and fair process.

Public policy: a government course of action (or inaction) adopted to address a public issue through laws, regulations, court rulings, or administrative decisions.

What issues reach the agenda

Political culture affects which problems become “public” rather than private:

Problems framed as threats to equal opportunity or public safety are more likely to gain traction.

Issues perceived as personal responsibility may face resistance to government intervention.

Appeals to rights (constitutional or civil) can elevate issues quickly, especially when tied to widely accepted ideals of fairness and liberty.

What goals policy pursues

Cultural values help define what success looks like:

Policies justified through opportunity often emphasise access (education, training, anti-discrimination enforcement).

Policies justified through liberty may prioritise limiting coercion, protecting privacy, and preserving due process.

Policies justified through order may emphasise enforcement capacity and compliance.

Because multiple values are in play, policy goals often involve trade-offs (for example, expanding access while preventing fraud, or increasing security while respecting civil liberties).

Acceptable tools and institutions

Political culture influences which institutions people trust to act:

Americans often show ambivalence toward national power, encouraging checks and balances, judicial involvement, and sunset provisions.

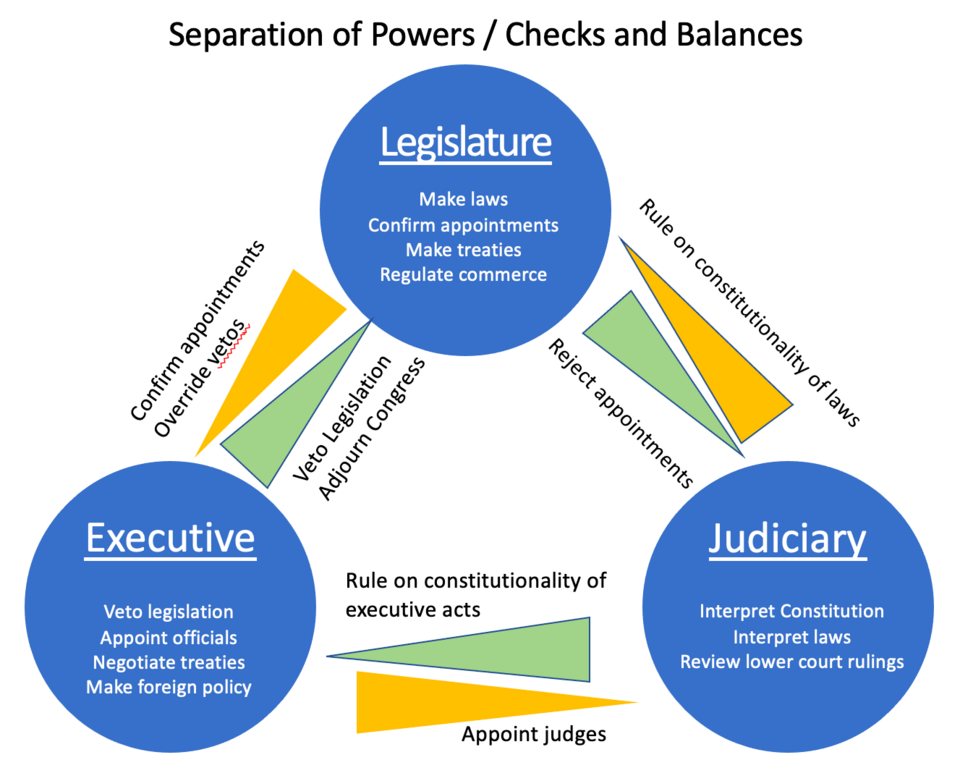

This diagram illustrates separation of powers across the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, emphasizing how each branch can check the others. It helps students see checks and balances as a structural response to concerns about concentrated power—an important element of U.S. political culture. The explicit arrows make it easy to connect abstract principles to concrete institutional tools. Source

Federalism expectations shape whether a national standard seems appropriate or whether states should tailor approaches.

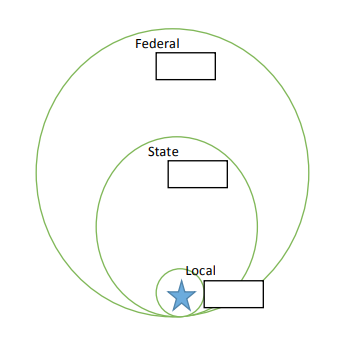

This worksheet diagram depicts federalism as a layered system of national, state, and local governments interacting with citizens. It reinforces the idea that many policy disputes are also disputes about which level should decide and administer rules. The visual is especially useful for connecting “federalism expectations” to real-world policy implementation. Source

Cultural support for free enterprise can push policymakers toward incentives, partnerships, or market-based mechanisms rather than direct provision.

How political culture shapes implementation over time

Even after adoption, cultural expectations continue to shape how policy is carried out and sustained.

Policy implementation: the process of putting a policy into effect through bureaucratic rules, enforcement decisions, funding, and programme administration.

Implementation reflects political culture through:

Compliance and legitimacy: people are more likely to follow rules they see as fair, constitutional, and evenly enforced.

Administrative design: culturally valued ideals like accountability can lead to reporting requirements, audits, and oversight—sometimes slowing delivery.

Rights-conscious governance: due process norms shape policing, benefits decisions, and regulatory enforcement, affecting how agencies operate.

Durability and feedback: policies that align with widely shared values are harder to repeal; policies seen as violating core norms face backlash, litigation, or underfunding.

Change over time: continuity and adaptation

Political culture is relatively stable, but its application shifts as circumstances and interpretations change. Over time, Americans may reinterpret the same value to justify different policy directions:

Liberty can support both deregulation (freedom from government constraints) and protections against private coercion (freedom from discrimination or exploitation).

Equality of opportunity can support anti-discrimination rules, school funding reforms, or limits on unfair barriers.

Rule of law can intensify demands for impartial enforcement, transparency, and anti-corruption measures, reshaping administrative practices.

Policy change is often incremental because policymakers must maintain cultural legitimacy. Major shifts typically require reframing new policies as consistent with established democratic ideals, principles, and core values, even when expanding or redirecting government action.

FAQ

They use multiple indicators to triangulate shared values and norms, such as survey questions on trust, rights, role of government, and civic duty.

Common approaches include:

Long-term polling trends across decades

Focus groups and qualitative interviews

Cross-state comparisons to detect subcultures

Content analysis of speeches, textbooks, and media framing

Yes. Values are abstract, so political actors debate their meaning.

For example, “liberty” may be framed as:

Freedom from government regulation, or

Freedom secured by government protections (e.g., anti-discrimination)

Policy conflict often reflects competing interpretations rather than rejection of the value itself.

Policies can embed benefits, rights expectations, and administrative routines that reshape what people view as normal or fair.

Over time, this can create:

Constituencies that defend the policy

New fairness baselines (“people deserve this”)

Institutional dependence (agencies, funding streams)

Immigration can shift the lived meaning of shared ideals by changing community experiences and political narratives.

Effects may include:

New coalition priorities

Reframing equality of opportunity and civic membership

Increased salience of language, education, and integration policy

These cultural shifts can alter policy agendas while constitutional rules remain constant.

They reinforce shared stories about national identity and democratic purpose.

In debates, politicians use these rituals to:

Claim moral legitimacy for a policy

Frame opposition as un-American or anti-democratic

Link policies to sacrifice, rights, or collective responsibility

This can shape which arguments resonate, even when the technical policy details are complex.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks) Explain one way U.S. political culture can influence what goals a public policy pursues.

1 mark: Identifies a relevant element of political culture (e.g., liberty, equality of opportunity, rule of law).

1 mark: Describes a plausible policy goal linked to that value (e.g., expanding access, limiting coercion, ensuring fair enforcement).

1 mark: Explains the linkage clearly (value shapes what counts as “success” or legitimate government purpose).

(4–6 marks) Analyse how U.S. political culture can affect both the formation and implementation of public policy over time.

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes political culture as shared democratic ideals/values/norms.

2 marks: Formation analysis (any two, 1 mark each): agenda-setting, policy goals, acceptable policy tools/institutions, legitimacy framing.

2 marks: Implementation analysis (any two, 1 mark each): compliance/legitimacy, administrative design and oversight, rights/due process constraints, durability/backlash and policy feedback.

1 mark: Over-time element: explains continuity/adaptation (reinterpretation of core values or incremental change driven by legitimacy).