AP Syllabus focus:

‘Because the United States is a democracy with a diverse society, policies made at any time reflect the attitudes and beliefs of citizens who participate in politics then.’

In the United States, public policy is not produced by “the public” equally. It is shaped by which groups participate, how diverse coalitions organise, and whose preferences decision-makers hear most clearly.

Participation as the Link Between Public Attitudes and Policy

In a democracy, citizen participation connects public beliefs to governing choices, but that connection is filtered by unequal engagement and unequal access to policymakers.

Forms of participation that matter for policy

Voting: selects officeholders who set agendas, write laws, and appoint officials.

Campaign activity: volunteering, donating, and mobilisation help decide which issues get emphasised.

Direct contact: calling, emailing, attending town halls, and meeting staff can signal intensity of preference.

Community and civic involvement: local organising can scale up into statewide or national policy pressure.

Participation affects policy outcomes because policymakers are attentive to:

electoral incentives (who can reward/punish them at the ballot box)

information and expertise (who provides credible policy details)

resources (time, money, and organisational capacity that sustain influence)

Diversity and the Reality of Many Publics

The United States is a diverse society with differences in race, ethnicity, religion, region, class, gender, age, and ideology. Diversity expands the range of policy demands but can also fragment participation if groups face different barriers or priorities.

Political participation: Activities by citizens intended to influence government or politics, such as voting, contacting officials, protesting, or working in campaigns.

Diversity can shape policy outcomes in two main ways:

Representation of interests: different communities prioritise different policy problems (for example, infrastructure, immigration, public safety, health access, or employment).

Coalition-building: durable policy change often requires alliances across groups; coalition partners may compromise, changing what the final policy looks like.

Participatory Inequality and Whose Preferences “Count” Most

Policies “reflect the attitudes and beliefs of citizens who participate,” but participation is uneven.

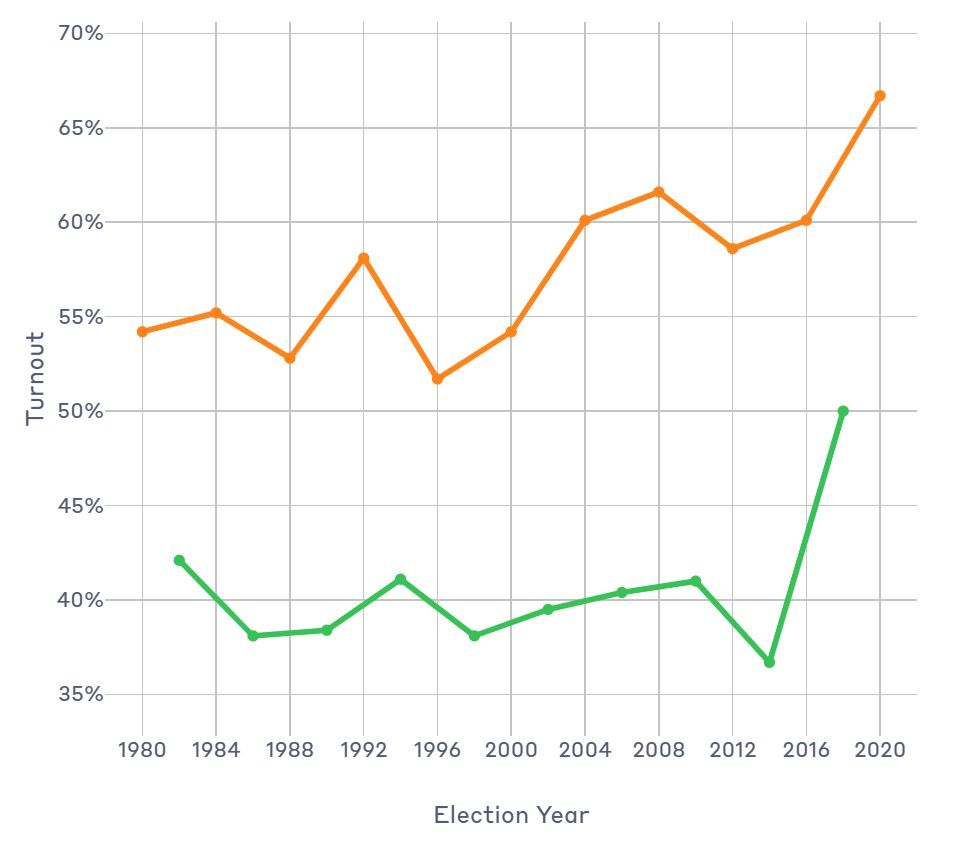

This line graph compares U.S. federal-election turnout over time, distinguishing higher-turnout presidential election years from lower-turnout midterm years. It highlights a recurring participation gap across election types, underscoring why policy feedback can be shaped disproportionately by the citizens most likely to vote in different cycles. Source

Groups with higher turnout, higher donation rates, and stronger organisations are more consistently heard, especially in:

primary elections (where smaller, more ideologically committed electorates can dominate)

low-salience elections (where turnout drops and becomes less representative)

complex policy areas (where expertise and sustained lobbying can outweigh broad public attention)

Common sources of participatory inequality include:

differences in time, income, education, and political efficacy (belief that one’s actions matter)

varying levels of mobilisation by parties, interest networks, and community leaders

structural barriers that can reduce participation for some groups (for example, limited access to transportation, childcare, or flexible work time)

How Participation and Diversity Produce Policy Outcomes

Policy results are best understood as the product of who shows up, how they organise, and what institutions respond to.

Mechanisms translating participation into policy

Agenda setting: highly active groups can elevate certain issues while others receive little attention.

Issue framing: participants shape how problems are defined (economic, moral, constitutional, or public safety frames), affecting which solutions seem acceptable.

Responsiveness: elected officials often prioritise the preferences of consistent participants because those preferences are more visible and politically consequential.

Majoritarian vs. pluralist pressures: broad public majorities can matter, but organised minorities can be influential when the broader public is disengaged or divided.

What “reflect” means in practice

Because participation is not equal, policy may reflect:

the median voter in high-turnout general elections on broad, visible issues

the most active and organised participants on technical, low-visibility, or highly polarised issues

shifting coalitions as demographic change and mobilisation alter which groups participate at a given time

Key Takeaways for AP Use

Policies are snapshots of the preferences of those participating then, not a perfect mirror of all public opinion.

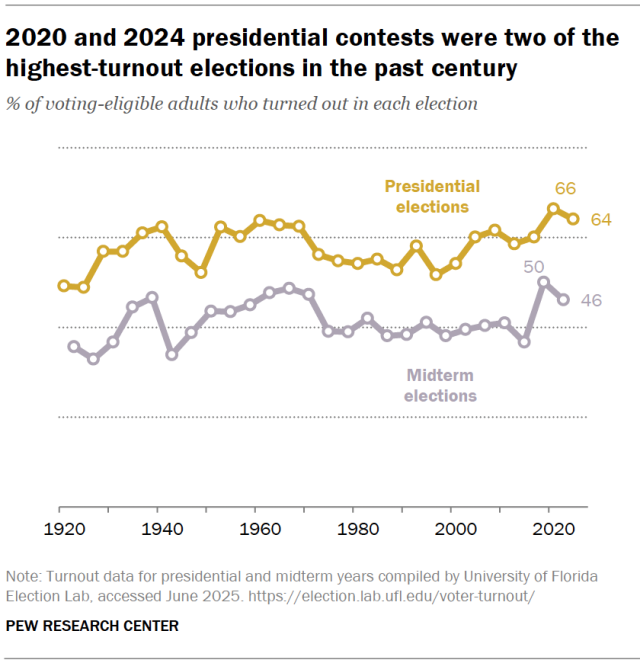

This chart tracks turnout in U.S. presidential and midterm elections across the past century, showing that participation rises in presidential years and drops in midterms. By flagging recent high-turnout cycles (including 2020 and 2024), it illustrates how the electorate’s size and composition can shift over time—altering which public attitudes are most visible to officials. Source

A diverse society increases the number of policy priorities and the need for coalitions.

Unequal participation can produce outcomes that are more responsive to frequent participants than to nonparticipants.

FAQ

Officials often weigh not only how many people agree, but how strongly they care.

High-intensity minorities may:

contact representatives repeatedly

attend meetings and public hearings

sustain organising over months/years

This can raise an issue’s priority relative to low-intensity majority views.

Descriptive representation is when officials share characteristics with constituents (e.g., race or gender).

Substantive representation is when officials advance constituents’ interests in policy.

In a diverse democracy, descriptive representation can affect trust and participation, while substantive representation determines whether participation translates into outcomes.

Language barriers and uneven access to reliable information can reduce participation by increasing the cost of engagement.

They can also shift which messages persuade voters, because groups may rely on different media sources and community networks, influencing which policy frames dominate.

Responsiveness tends to be higher when issues are:

highly visible to the public

easy to attribute to officeholders

tied closely to elections

Technical or low-salience issues often reward sustained participation and expertise, which can amplify organised voices.

When groups are geographically concentrated, they can become pivotal in particular districts or states, increasing leverage with specific representatives.

When groups are dispersed, influence may depend more on nationwide mobilisation, coalition-building, and coordinated participation across many constituencies.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Explain one reason why public policy may reflect the preferences of citizens who participate more than those who participate less.

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., elected officials respond to turnout, donors, or organised groups).

1 mark: Explains how this increases political attention/influence (e.g., officials fear electoral punishment or rely on campaign resources).

1 mark: Links to policy outcomes (e.g., agendas/laws prioritise issues important to active participants).

(6 marks) Using your knowledge of participation and diversity in the United States, explain how a diverse society can produce policy outcomes that differ across time, even when overall public attitudes change only slightly.

1 mark: Describes diversity as multiple groups with different priorities.

1 mark: Explains coalition-building/compromise changing policy content.

1 mark: Explains participatory inequality (some groups participate more consistently).

1 mark: Connects changing mobilisation/turnout to which preferences are most visible.

1 mark: Links to institutional responsiveness (agenda setting, framing, or electoral incentives).

1 mark: Concludes with time variation in outcomes due to shifting participating coalitions, not just average opinion.