AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political efficacy, the belief that participation can make a difference, influences whether people choose to vote.’

Political participation is not only shaped by laws and institutions but also by psychology. Political efficacy helps explain why some eligible citizens vote reliably while others disengage, even when voting is easy and legal.

Core idea: efficacy connects beliefs to behaviour

Political efficacy links a person’s attitudes to a decision to participate (especially voting). When people think their voice matters and government is responsive, they are more likely to invest time, attention, and effort into politics.

Key definition

Political efficacy: The belief that one’s political actions (such as voting or contacting officials) can influence government and that government will respond to citizens.

Efficacy is not the same as partisanship, ideology, or knowledge, but it often interacts with all three: feeling capable and heard makes learning about politics and turning out to vote more likely.

Types of political efficacy

Political efficacy is commonly discussed in two parts, which can move independently.

Internal efficacy (confidence in oneself)

Internal efficacy is the belief that you personally understand politics well enough to participate effectively.

Higher internal efficacy is associated with:

greater political interest and attention

feeling qualified to discuss issues or evaluate candidates

higher likelihood of voting, especially in lower-salience elections

Lower internal efficacy can lead to:

“politics is too complicated” attitudes

avoiding registration, campaigns, or ballot measures

reliance on simple cues (party label) or nonparticipation

External efficacy (trust in responsiveness)

External efficacy is the belief that government and officials will listen and respond to ordinary people.

Higher external efficacy is associated with:

willingness to vote because outcomes seem meaningful

contacting representatives or participating in community politics

Lower external efficacy is associated with:

cynicism (“they don’t care what people like me think”)

apathy or protest-oriented participation rather than voting

disengagement after negative experiences with institutions

How efficacy shapes participation decisions

Voter participation is a choice under limited time, imperfect information, and competing responsibilities. Efficacy influences how people answer three practical questions.

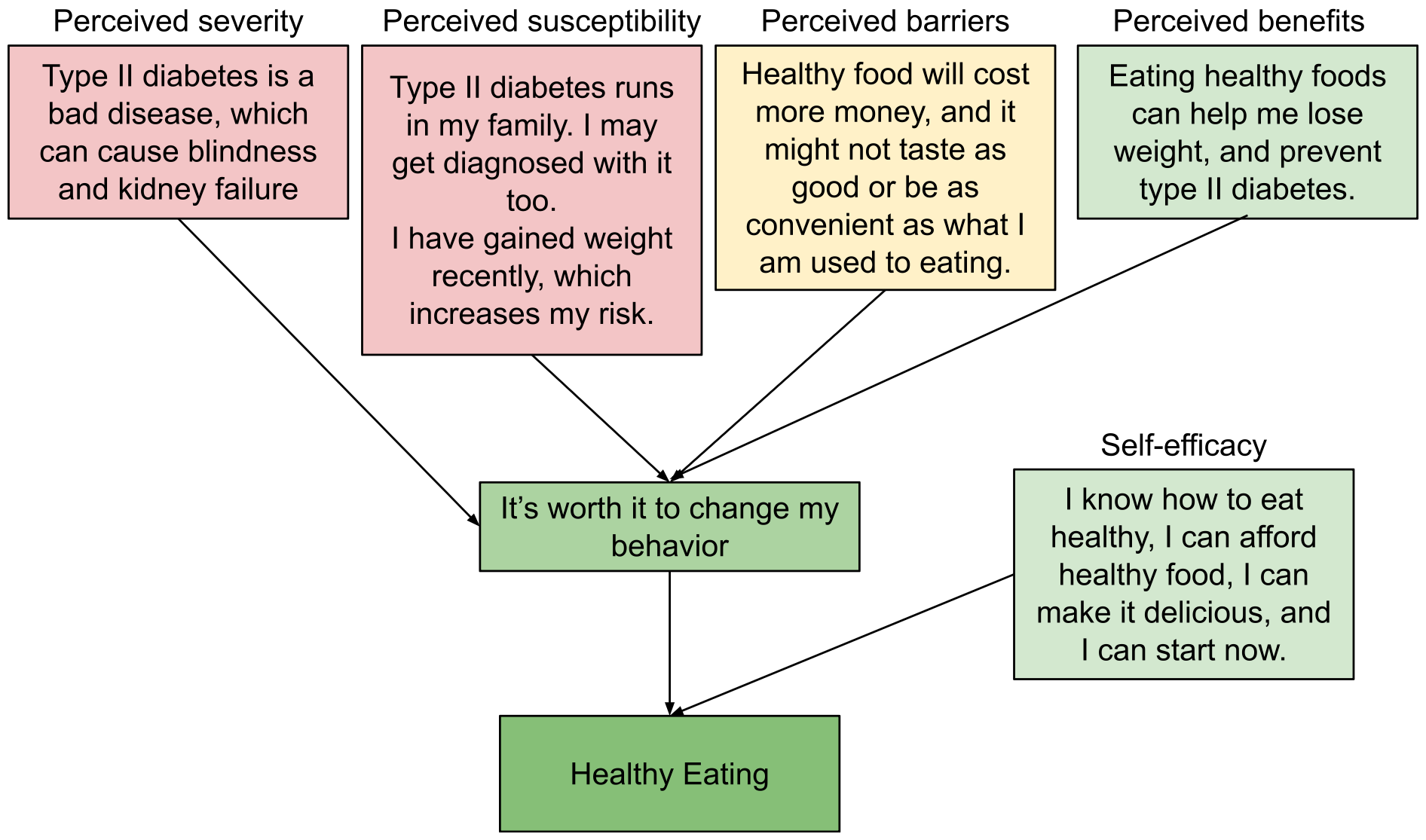

A decision-model diagram showing how beliefs about costs/benefits feed into whether an action seems worthwhile, while self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability) helps translate intention into behavior. Although the example is from health behavior, the structure maps well onto voting: efficacy functions like an internal “can I do this?” mechanism within a broader participation choice. Source

1) “Is it worth it?”

High efficacy increases the perceived benefit of voting: if participation can make a difference, voting seems worthwhile.

People with low efficacy may see voting as symbolic rather than impactful.

High efficacy can sustain participation even when elections feel predictable.

2) “Can I do it competently?”

Internal efficacy affects whether individuals feel able to pick candidates, understand issues, and navigate the ballot.

Confusing ballots, unfamiliar offices, or complex policy debates can depress turnout more among low-internal-efficacy voters.

Campaigns that provide clear explanations and accessible information can indirectly raise participation by boosting internal efficacy.

3) “Will anyone listen?”

External efficacy affects whether people believe institutions translate votes into policy.

If government seems unresponsive, citizens may decide that the costs of participation outweigh the benefits.

Perceptions of corruption, unequal influence, or broken promises can reduce external efficacy and therefore turnout.

What increases or decreases political efficacy

Political efficacy is shaped over time through socialisation and lived experience. It is not fixed.

Factors that can raise efficacy

Civic education and political knowledge: understanding processes and rights increases internal efficacy.

Positive contact with government: seeing an issue addressed or receiving a helpful response can raise external efficacy.

Social support and mobilisation: encouragement from family, peers, or organisations can increase confidence and reduce uncertainty about participation.

Community engagement: local problem-solving and volunteering can build skills that transfer into political participation.

Factors that can lower efficacy

Distrust and alienation: repeated disappointment, polarisation, or perceived “insider” politics can lower external efficacy.

Information overload or misinformation: confusion can lower internal efficacy and produce withdrawal.

Feeling socially marginalised: believing that leaders ignore one’s group can reduce external efficacy, especially if reinforced by personal experience.

Efficacy and turnout patterns

Efficacy helps explain turnout differences across individuals and across election contexts.

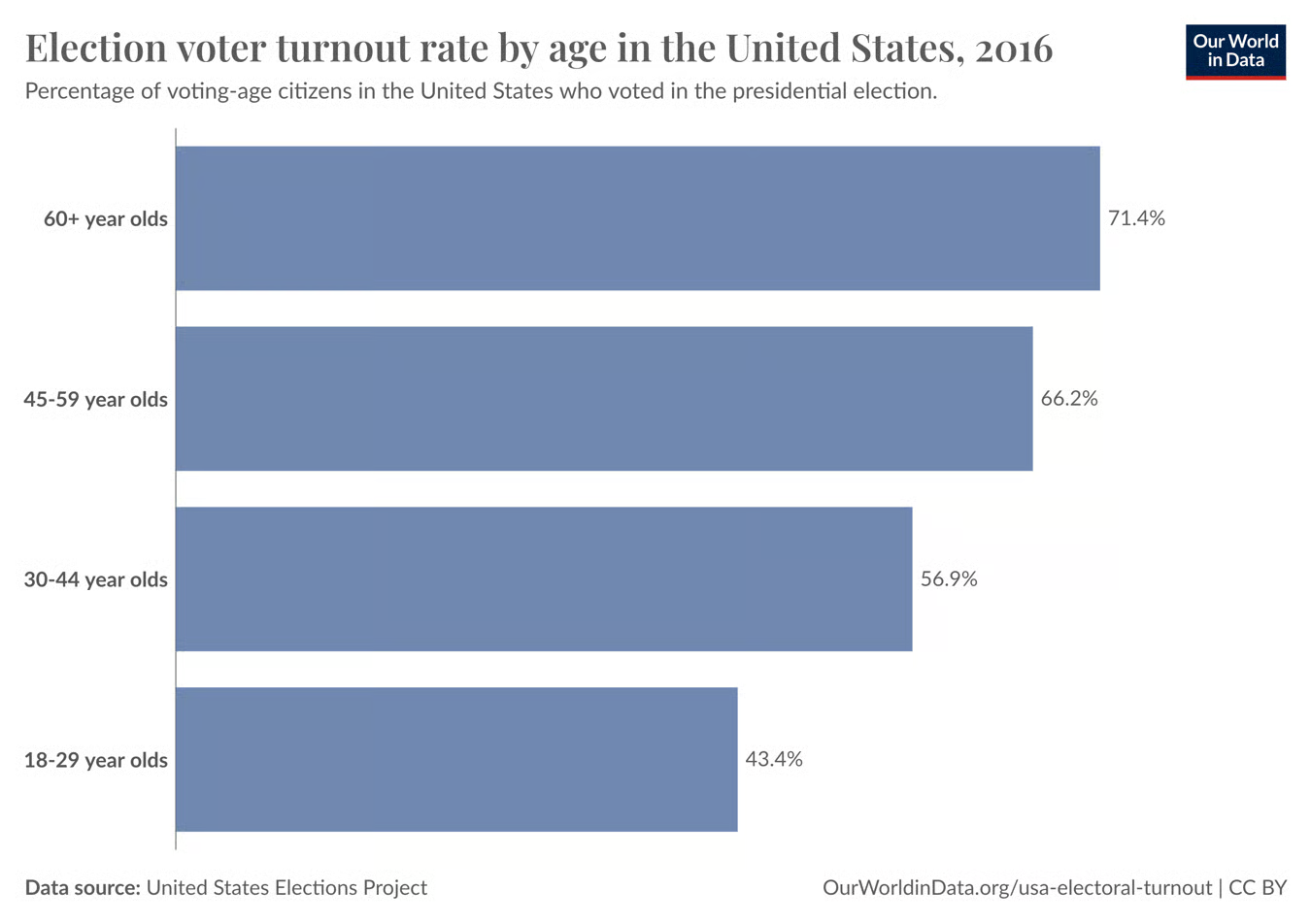

A set of bar/line charts showing voter turnout rates by age group in U.S. presidential elections (e.g., younger voters participating at lower rates than older voters). This kind of descriptive turnout pattern helps ground efficacy arguments in observable participation gaps that political behavior theories aim to explain. Source

In high-salience elections, some low-efficacy citizens may still vote due to social pressure, strong emotions, or high media attention.

In low-salience elections, efficacy matters more because fewer outside cues push people to the polls.

Efficacy can also shape whether people become “habitual voters”: repeated participation can build confidence and reinforce beliefs that participation matters.

FAQ

Typically through Likert-scale items.

Common internal items: “I consider myself well qualified to participate in politics.”

Common external items: “Public officials care what people like me think.”

It can change quickly after major events.

Short-term shifts often follow scandals, crises, or a highly salient policy outcome.

Long-term stability comes from education, family socialisation, and repeated participation.

Trust is broader and more evaluative (honesty, integrity).

External efficacy overlaps with trust but is more about responsiveness and influence.

A person may distrust politicians yet still feel efficacious about voting’s impact.

They may feel informed and capable but believe institutions are unresponsive.

This combination can produce participation that targets accountability (e.g., contacting officials, activism) or, in some cases, withdrawal from voting.

They can, but effects vary.

Can raise internal efficacy via information and discussion.

Can lower external efficacy if communities reinforce cynicism about institutions.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define political efficacy and explain one way it can influence whether a citizen votes.

1 mark: Correct definition of political efficacy (belief participation can make a difference / government responsiveness).

1 mark: Explains a valid influence on voting (e.g., higher efficacy increases likelihood of turnout; low efficacy leads to apathy).

(6 marks) Explain the difference between internal and external political efficacy and analyse how each can affect participation decisions.

1 mark: Defines internal efficacy (confidence in one’s own understanding/ability to participate).

1 mark: Defines external efficacy (belief government will respond to citizens).

2 marks: Analysis of internal efficacy effects on participation (e.g., confidence navigating information/ballot; low internal efficacy reduces turnout).

2 marks: Analysis of external efficacy effects on participation (e.g., responsiveness encourages voting/contacting; low external efficacy leads to disengagement or protest).