AP Syllabus focus:

‘Demographics and political efficacy or engagement are used to predict the likelihood that an individual will vote.’

Understanding who votes helps explain turnout gaps and campaign strategy. In the United States, demographic characteristics and measures of political engagement/efficacy are commonly used to estimate an individual’s likelihood of voting.

What “predicting who votes” means

Analysts, campaigns, and scholars use observable traits and attitudes to estimate the probability that a person will participate in an election. These predictors do not guarantee behaviour; they identify patterns in aggregate and probabilistic tendencies at the individual level.

Key idea: turnout is patterned, not random

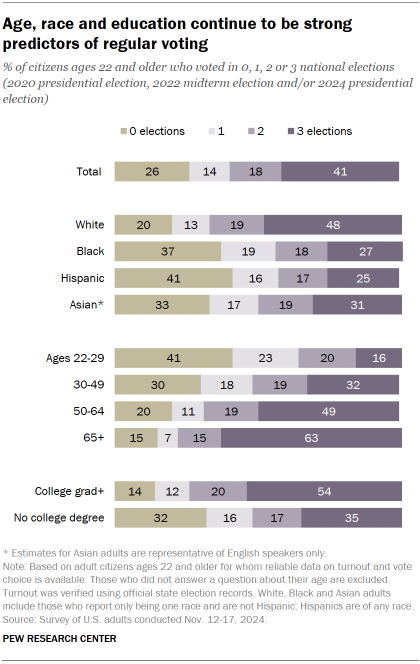

Stacked bars show the share of citizens who voted in 0, 1, 2, or 3 of the last three national elections, broken out by age, race/ethnicity, and education. The graphic makes “predicting who votes” concrete by showing that older and more-educated groups are much more likely to be consistent (habitual) voters. This illustrates how demographic traits are used as probabilistic predictors of participation rather than guarantees. Source

Voting is shaped by resources (time, money, skills), motivation, and mobilisation.

Predictors often work together; no single factor fully explains turnout.

Demographic predictors commonly linked to turnout

Demographics correlate with voting largely because they are associated with differences in resources, life stability, social networks, and exposure to political information.

Age and life-cycle effects

Older citizens tend to vote at higher rates than younger citizens.

Reasons often include more stable residence, stronger community ties, and more habitual voting.

Education

Educational attainment is one of the strongest predictors of voting.

More education is associated with higher political knowledge, easier navigation of election information, and more confidence interacting with institutions.

Income and socioeconomic status

Higher-income individuals generally vote more often than lower-income individuals.

Income can affect access to transportation, flexibility in work schedules, and the ability to follow politics consistently.

Race and ethnicity (as contextual predictors)

Turnout patterns differ across groups and across elections.

Differences often reflect varying mobilisation efforts, community networks, and historically shaped political experiences.

Gender

In many modern elections, women’s turnout has been comparable to or higher than men’s turnout.

The size and direction of any gender gap can vary by election context and group.

Residential stability and mobility

People who move frequently tend to vote less, in part because moving disrupts registration status, local connections, and awareness of down-ballot races.

Community context

Predictive models may incorporate neighbourhood cues (e.g., local turnout history), because social environments influence political discussion and mobilisation.

Political engagement and political efficacy as predictors

Demographics capture “who someone is,” while engagement measures capture “how connected” someone is to politics.

Political efficacy: the belief that one’s political participation matters and that government will be responsive to citizen action.

Engagement indicators linked to higher likelihood of voting

Political interest: how much attention a person pays to politics and campaigns.

Political knowledge: familiarity with issues, candidates, and institutions.

Partisanship: stronger party identification is often linked to higher turnout because it simplifies choices and increases motivation.

Civic skills and discussion: comfort discussing politics, following news, and participating in community life.

Previous voting history: past participation is a strong predictor of future participation because voting can become habitual.

Efficacy’s role in prediction

Higher efficacy is associated with a greater sense that voting is worthwhile.

Lower efficacy is associated with disengagement and the belief that elections will not change outcomes.

How these predictors are used

Predictors are used to estimate likelihood, not to label individuals as certain voters or non-voters.

In campaign strategy (turnout targeting)

Campaigns prioritise outreach to “likely voters” and “persuadable” groups using demographic and engagement signals.

Mobilisation is often concentrated where small increases in turnout could affect outcomes.

In research and polling

Pollsters use demographic weighting and screening to model the electorate.

Researchers compare groups to identify turnout gaps and test explanations related to resources and engagement.

Limits and cautions when using predictors

Correlation is not causation: demographics may proxy underlying factors like time, information, and network mobilisation.

Intersectionality matters: effects differ when traits combine (e.g., age with education, or income with mobility).

Context matters: competitiveness, salient issues, and local conditions can shift which groups turn out.

Avoid overgeneralising: group averages do not determine an individual’s behaviour.

FAQ

They combine signals such as past turnout, stated interest, and demographic correlates.

They validate models by comparing predictions to actual turnout after elections.

Education is linked to civic skills (processing information, completing forms, evaluating claims).

It also correlates with political discussion networks and confidence engaging with institutions.

Yes. Someone may believe their vote matters (high efficacy) while distrusting officials (low trust).

That mix can still predict turnout, especially if the person votes to demand change.

Moving disrupts routines and weakens local social ties used for mobilisation.

It can also change eligibility/registration status, making turnout less consistent over time.

Salient events, polarising candidates, or high-stakes issues can mobilise normally low-turnout groups.

Shifts in mobilisation efforts can change which predictors matter most in that cycle.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify two demographic characteristics that are commonly used to predict whether an individual is likely to vote.

1 mark for each correct characteristic identified (e.g., age, education, income, residential stability, race/ethnicity, gender).

(6 marks) Explain how demographics and political engagement or efficacy can be used together to predict the likelihood that an individual will vote. In your response, describe one limitation of using these predictors.

1 mark: explains that demographics correlate with resources/opportunity that affect turnout.

1 mark: links a specific demographic (e.g., education or age) to higher/lower likelihood of voting.

1 mark: explains political engagement (interest/knowledge/party identification) as a predictor of turnout.

1 mark: explains political efficacy as a predictor (belief participation matters increases likelihood).

1 mark: explains combined use (models/targeting/likely voter estimates based on multiple indicators).

1 mark: states a valid limitation (context changes, correlation not causation, intersectionality, group averages not determinative).